Andrey Vladimirovich Nikolaev was born in 1922 in Moscow, and soon after school, he entered the Veliky Ustyug Infantry School, from which he graduated as a lieutenant in 1942.

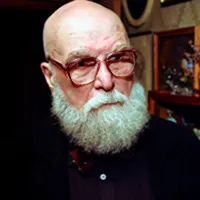

After the war, he graduated with honors from the All-Union Institute of Cinematography from the Department of Film Art Direction. As an illustrator, he worked with the publishing houses Goslitizdat, Detgiz, Sovetsky Pisatel, Molodaya Gvardiya, and the magazines Yunost, Smena, Rabotnitsa, and others. In nearly half a century of work, he created illustrations for two hundred literary works: he illustrated Pushkin, Alexei Tolstoy, Maxim Gorky, Émile Zola, and many other writers. Additionally, he is known in close circles for his literary and theological works, as well as extensive memoirs (though he did not seek to publish them).

Nikolka's friend, the guitar, sounded a soft, muffled strum... An uncertain strum... because, you see, nothing was really known for sure yet. It was restless in the City, foggy, and bad...

“The Hetman, huh? Son of a bitch!” Myshlayevsky roared. “Cavalry Guard? In the palace? Huh? And they sent us out in whatever we were wearing. Huh? A day in the frost and snow... Lord! I thought we were all done for... To hell with them! An officer a hundred sazhen apart from another—is that what they call a chain? They almost slaughtered us like chickens!”

In silence, they returned to the dining room. The guitar was grimly silent. Nikolka dragged the samovar from the kitchen, and it sang ominously and sputtered. On the table were cups with delicate flowers on the outside and gold on the inside, special ones, shaped like figured columns. When their mother, Anna Vladimirovna, was alive, this was the festive service for the family, but now the children used it every day.

Elena was alone and therefore didn't hold back, conversing in a low voice or silently, barely moving her lips, with the hood filled with light and the two black spots of the windows: “He's gone...”

And in the third car from the locomotive, in a compartment covered with striped seat covers, Thalberg sat opposite a German lieutenant, smiling politely and ingratiatingly, and spoke in German.

And so, in the winter of 1918, the City lived a strange, unnatural life that might never be repeated in the twentieth century. Behind the stone walls, all the apartments were overflowing. Its ancient, native inhabitants huddled together and continued to shrink, willingly or unwillingly letting in the new arrivals who flocked to the City. And those people came precisely across this arrow-shaped bridge from where the mysterious, grayish haze was.

On the black, deserted street, a tattered gray wolf-like figure silently climbed down from the branch of an acacia tree, where he had been sitting for half an hour, suffering in the frost but greedily observing the work of the engineer through a treacherous gap above the top edge of the sheet, an engineer who had brought trouble upon himself with the very sheet on his green-painted window.

It's a good thing Feldman died an easy death. Sotnik Halanba didn't have the time. So he simply swiped his saber at Feldman's head.

“Excellent-s. Division, attention!” he suddenly roared, so that the division instinctively flinched. “Listen!! The Hetman, at about four o'clock this morning, shamefully abandoned all of us to our fate and fled! He fled like the lowest scoundrel and a coward! Today, an hour after the Hetman, the commander of our army, General of Cavalry Belorukov, also fled to the same place as the Hetman, that is, to the German train. In no more than a few hours, we will witness a catastrophe when people like you, deceived and drawn into this adventure, will be killed like dogs.”

The clatter of bolts ran through the cadet chains, Nai took out a whistle, blew it shrilly, and shouted:

“Dwectly at the cavawwy!.. volleys... fiwe!”

Then Colonel Nai-Turs was lying at Nikolka's feet. A black haze enveloped Nikolka's brain; he squatted down and, unexpectedly for himself, with a dry sob and no tears, began to pull the colonel by the shoulders, trying to lift him. Then he saw that blood was flowing from the colonel's left sleeve, and his eyes had rolled up to heaven.

Turbin fell silent, closing his eyes. From the wound high up near his left armpit, a dry, prickly heat spread through his body. At times, it filled his entire chest and clouded his head, but his feet were unpleasantly freezing.

The apparition was in a brown tunic, brown riding breeches, and boots with yellow jockey flaps. The eyes, muddy and sorrowful, looked out of the deepest sockets of an incredibly huge, short-clipped head. The apparition was undoubtedly young, but the skin on its face was old, grayish, and its teeth looked crooked and yellow. In the apparition's hands was a large cage with a black scarf thrown over it and an unsealed blue letter...

On the second of February, a black figure with a shaved head covered by a black silk cap walked through the Turbin apartment. It was Turbin himself, resurrected. He had changed dramatically. On his face, at the corners of his mouth, two folds seemed to have dried forever, his skin was waxy, and his eyes were sunken in shadows and had become permanently unsmiling and gloomy.

The man walked methodically, with his bayonet lowered, and thought only of one thing: when the hour of frosty torture would finally expire and he would go inside from the maddened earth, where pipes giving off a divine heat warmed the troop trains, where in a cramped doghouse he could collapse onto a narrow bunk, press himself against it, and lie sprawled out. The man and his shadow walked from the fiery splash of the armored belly to the dark wall of the first combat car, to the place where the inscription was black: “Armored Train ‘Proletary’.”