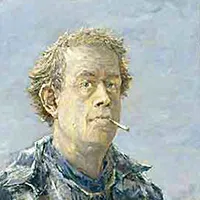

Sergei Mikhailovich Chepik (1953–2011) was born in Kyiv, Bulgakov's beloved city, into a family of artists.

He graduated from the Faculty of Monumental Painting at the I. E. Repin Leningrad State Academic Institute of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture (in the workshop of A. A. Mylnikov). In 1988, he emigrated to France and lived and worked in Paris from then on.

Sergei Chepik worked not only in illustration, painting, and easel graphics but also in ceramics and sculpture.

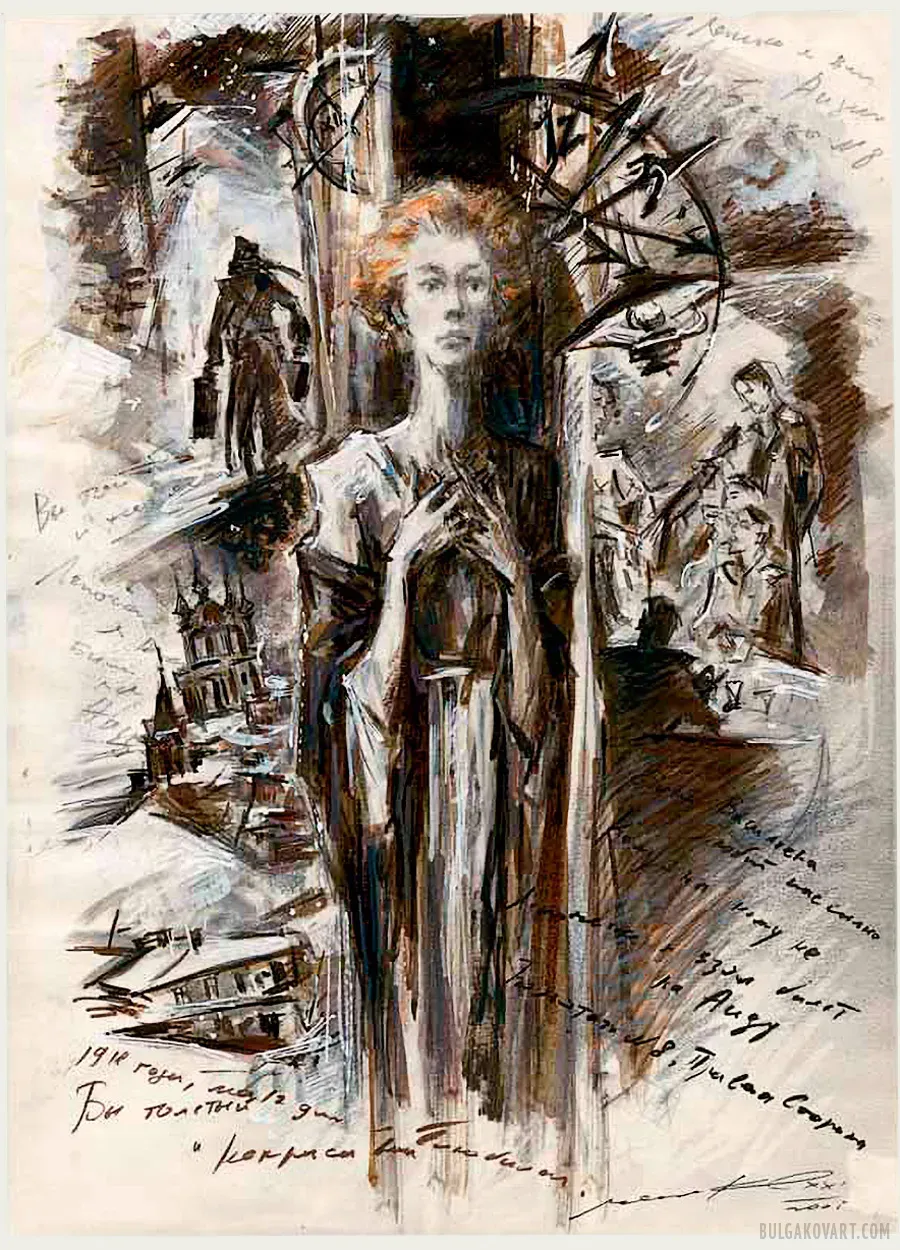

But we are interested in his works on Bulgakov. It must be said that Sergei Mikhailovich's maternal grandfather—a representative of the famous noble family of Sabaneev—was Bulgakov's classmate at the First Kyiv Gymnasium and at the Medical University. During the days described in The White Guard, his relatives died defending Kyiv from Petliura's gangs. It is said that after graduating from university, Sabaneev corresponded with Bulgakov and even traveled to Moscow to see him. It is also said that Elena Sergeevna, Bulgakov's widow herself, gave Sabaneev a copy of the as-yet-unpublished novel The Master and Margarita, which he read to his grandson, Sergei. In all honesty, these stories sound very much like family legends, but regardless, Sergei Mikhailovich's illustrations for Bulgakov are worthy of all admiration.

For The White Guard, the artist created about forty illustrations, but as is often the case, only some of them can be found online. Well, that's better than nothing.

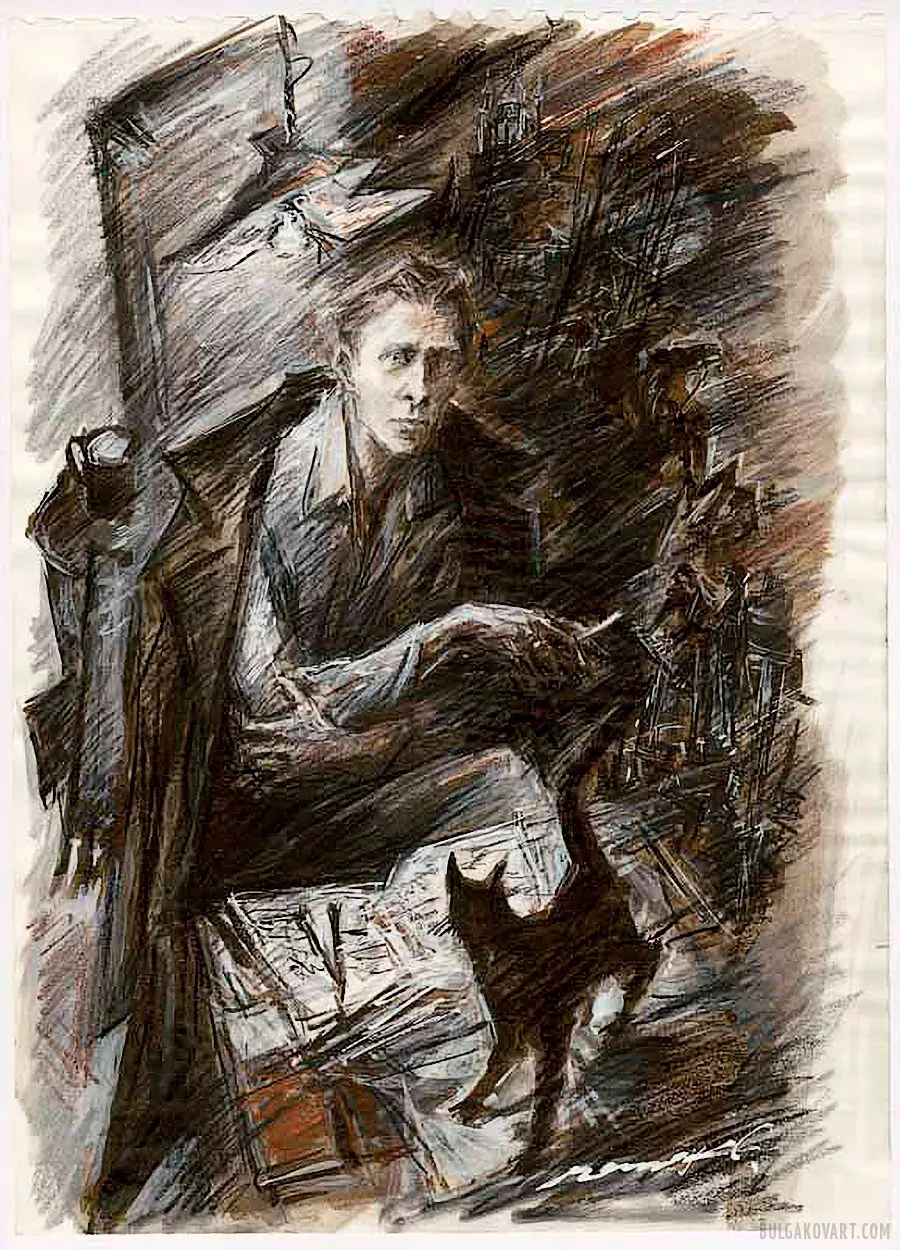

Bulgakov writes the novel:

“I pulled my barrack lamp as close as possible to the table and put a shade made of pink paper over its green shade, which brought the paper to life. On it, I wrote the words: 'And the dead were judged out of those things which were written in the books, according to their works.' Then I began to write, not yet knowing what would come of it. I remember that I really wanted to convey how good it is when the house is warm, the tower clock strikes in the dining room, the drowsy nap in bed, the books, and the frost. Writing is generally very difficult, but for some reason, this came easily. I had no intention of ever publishing it.”

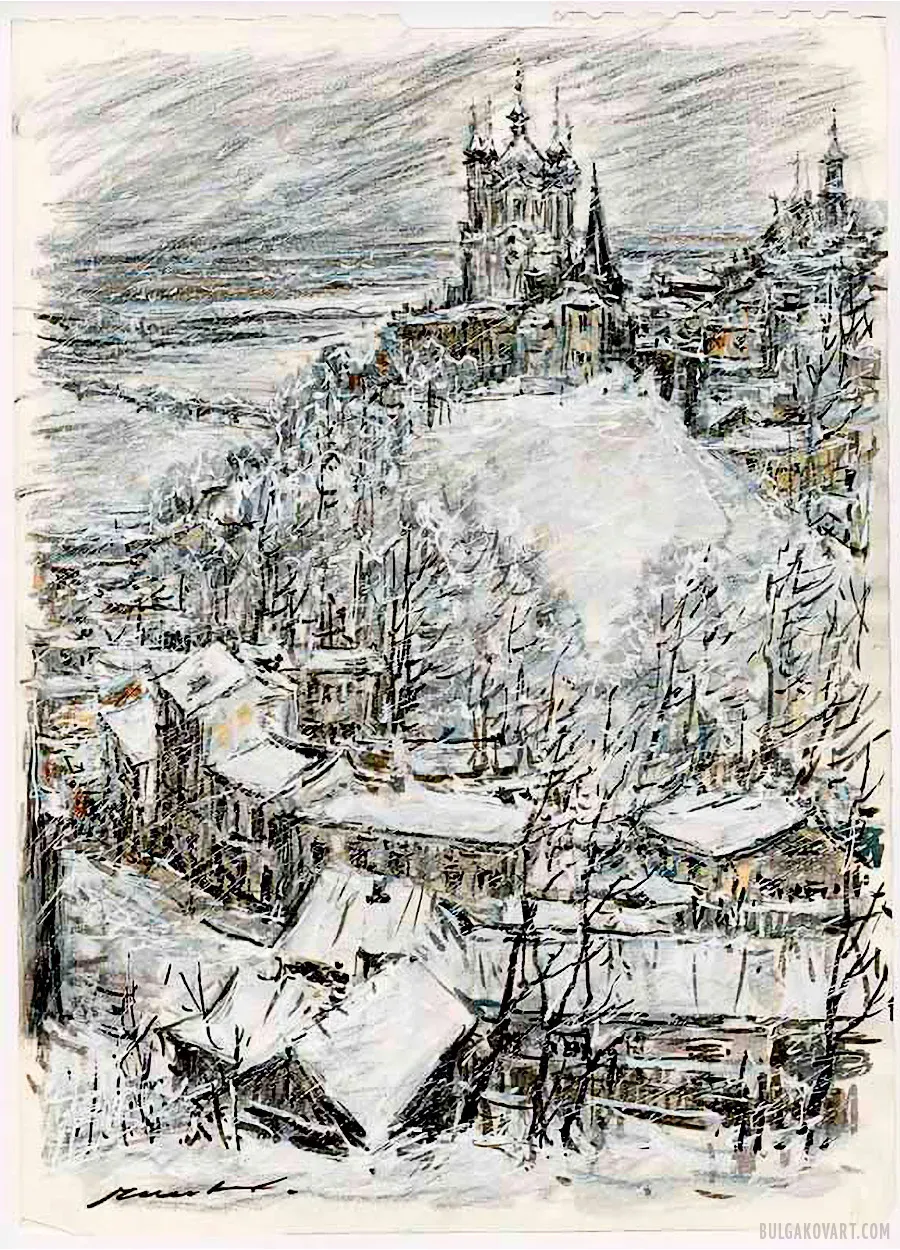

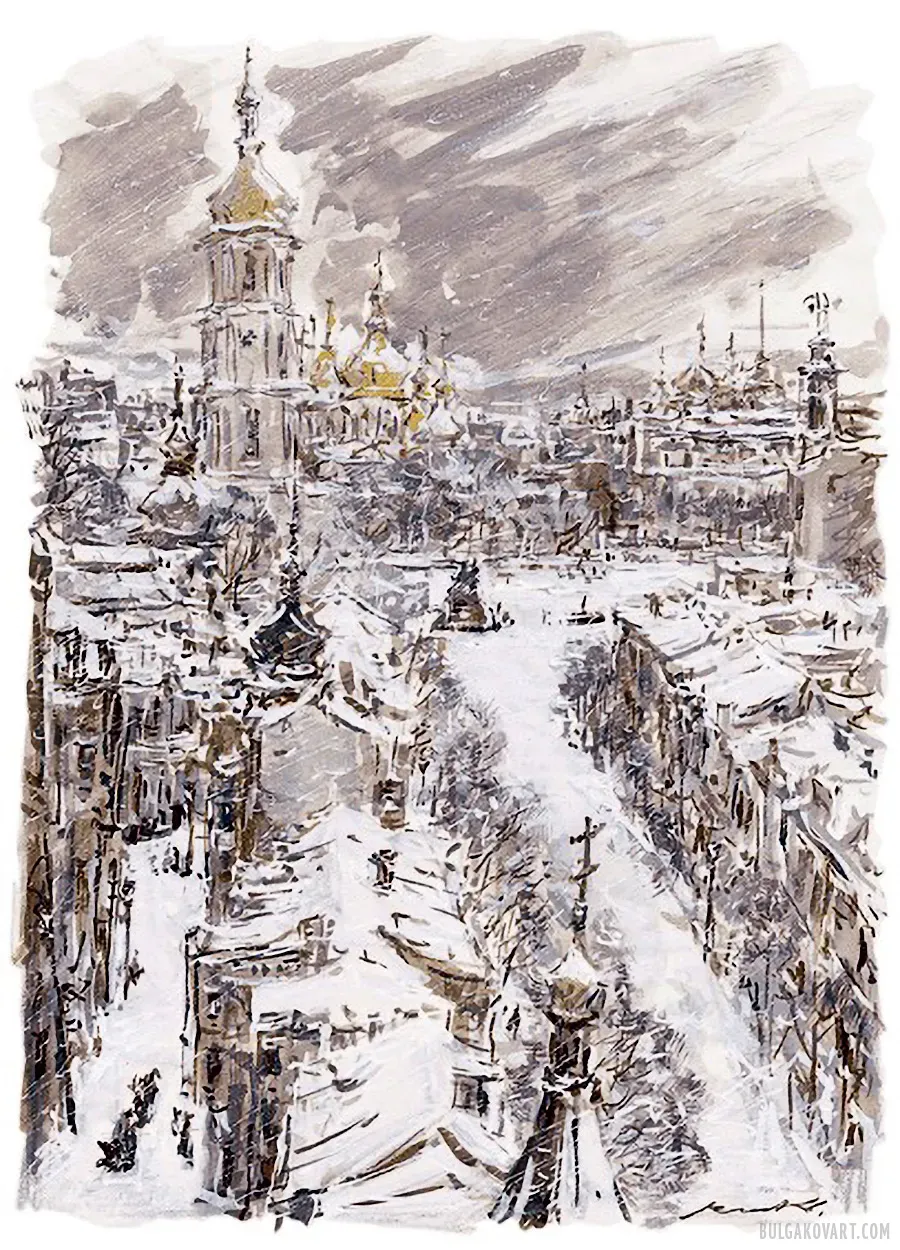

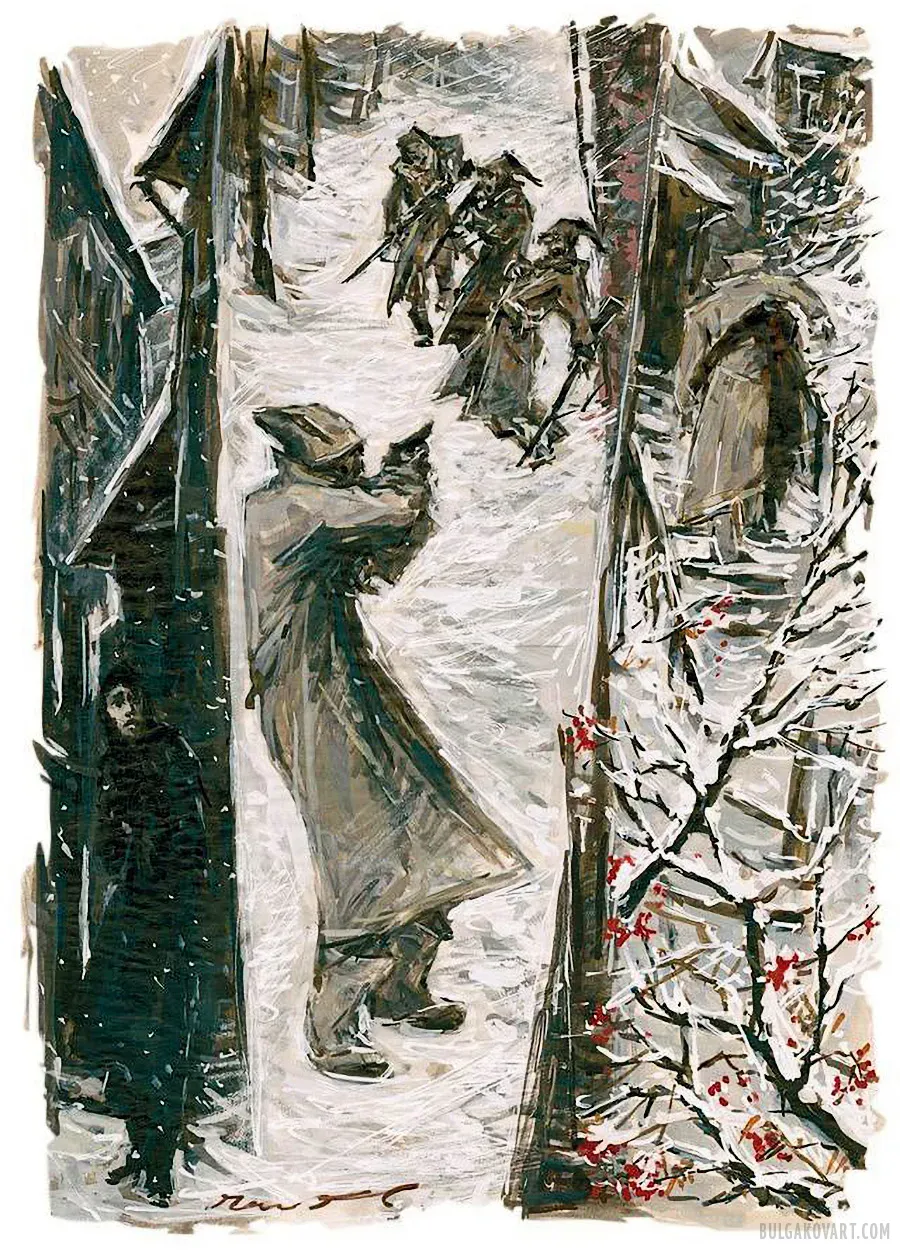

Like multi-tiered honeycombs, the City smoked and buzzed and lived. Beautiful in the frost and fog on the hills, over the Dnieper. The streets steamed with haze, and the giant, trodden snow squeaked. And the houses piled up in five, and six, and seven stories.

The gardens stood silent and calm, laden with white, untouched snow. And there were so many gardens in the City, more than in any other city in the world. They spread everywhere in huge patches, with avenues, chestnuts, ravines, maples, and lindens.

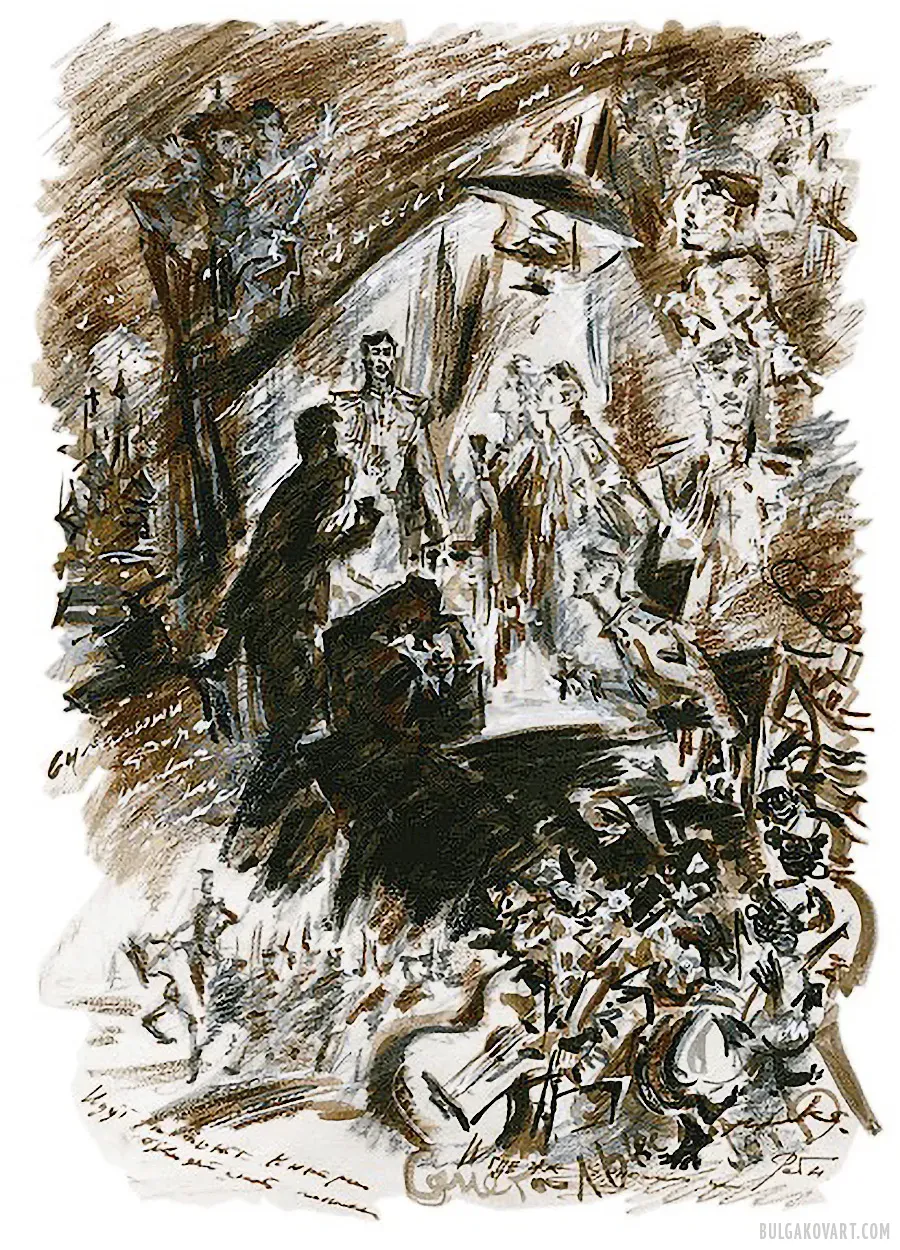

Shervinsky was not particularly drunk; he raised his hand and said powerfully:

“Don't rush, but listen. N-now, I ask the officers (Nikolka blushed and paled) to be silent for now about what I am about to tell you.”

The little uhlan immediately felt that his voice was better than ever, and the pinkish living room was filled with a truly monstrous hurricane of sounds; Shervinsky sang an epithalamium to the god Hymen, and how he sang! Yes, perhaps everything else in the world is nonsense, except for a voice like Shervinsky's.

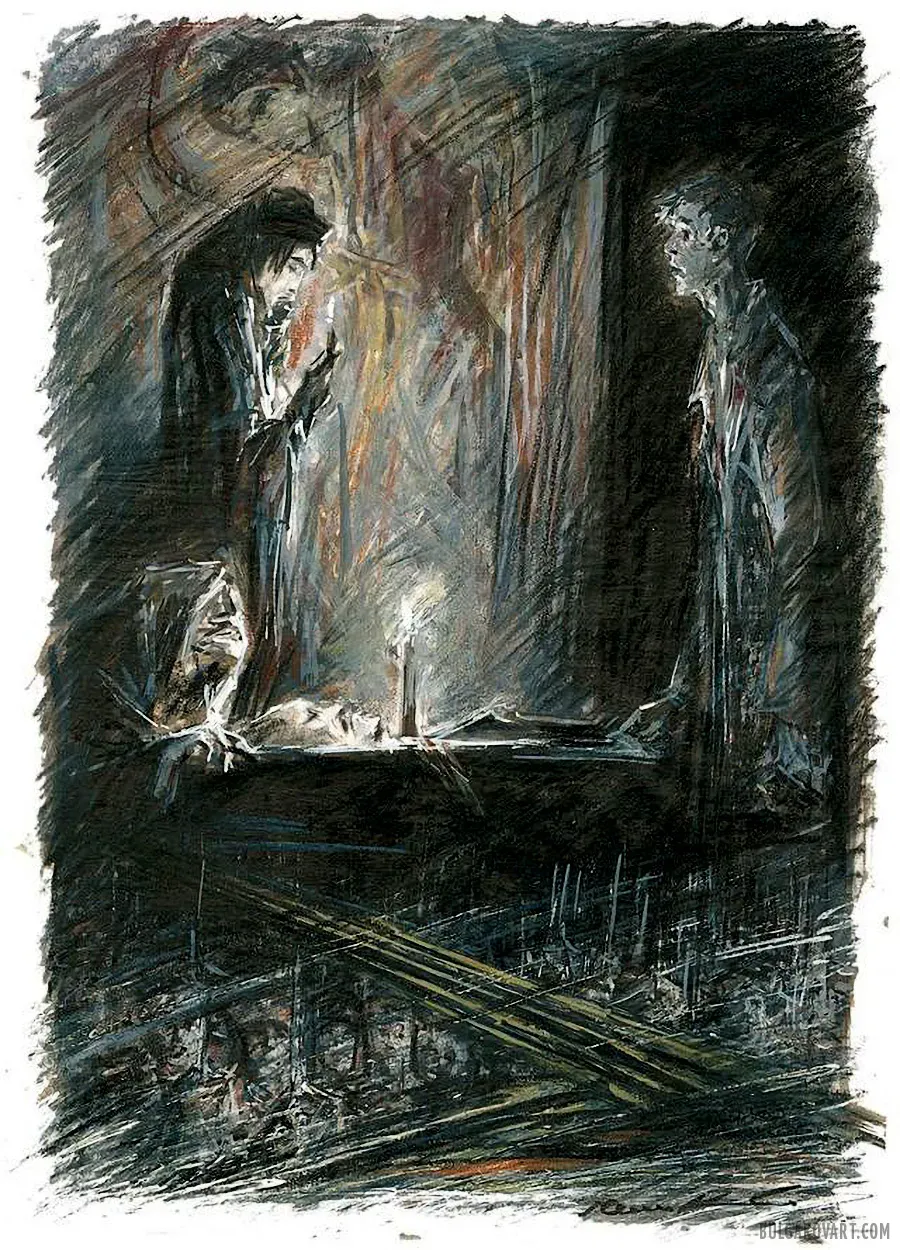

“Are you in paradise, Colonel?” Turbin asked, feeling a blissful tremor that a person never experiences in a waking state.

“I'm in pawadise,” Nai-Turs answered in a voice as pure and completely transparent as a stream in the city's forests.

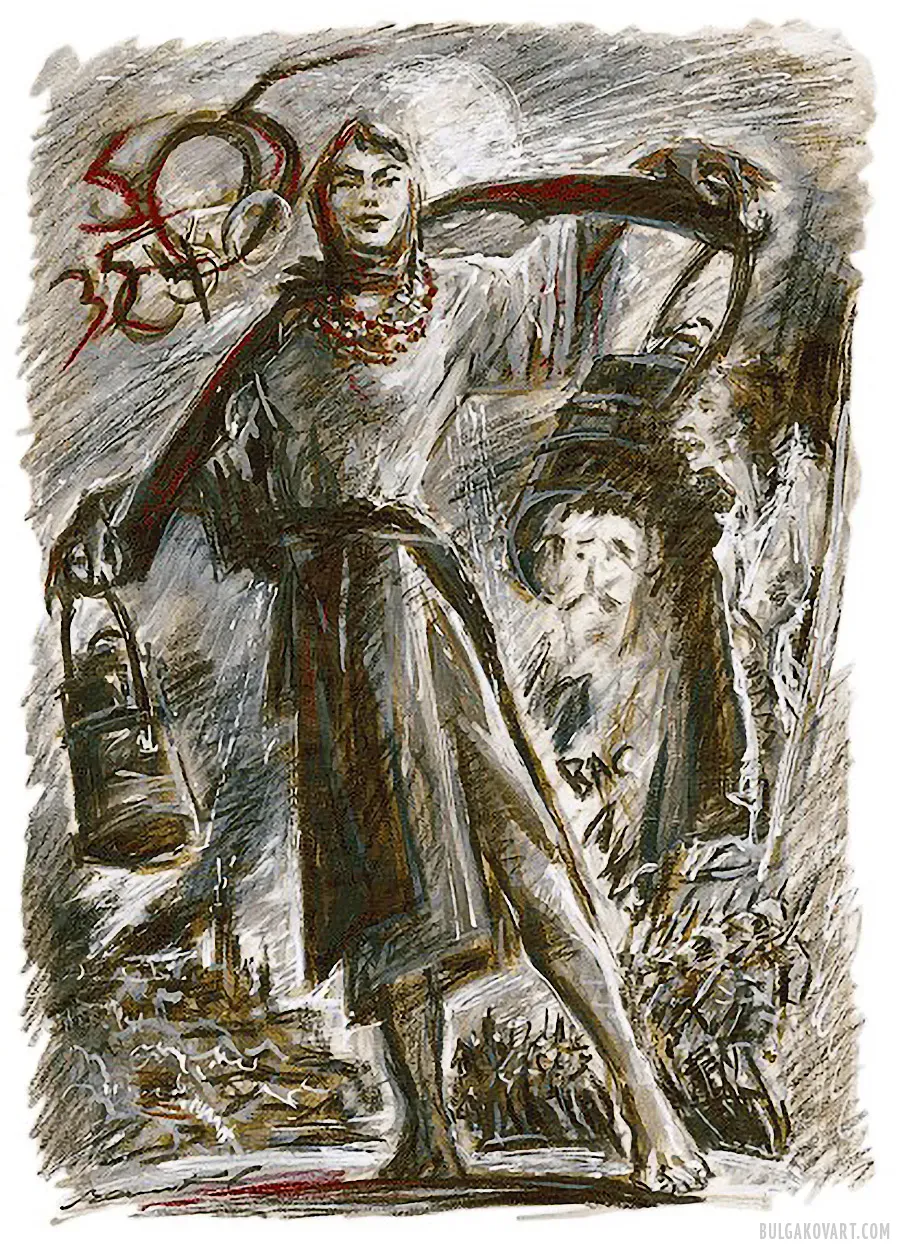

Very early, very early, when the sun sent a cheerful ray into the gloomy dungeon leading from the courtyard to Vasilisa's apartment, he, looking out, saw a sign in the ray. It was incomparable in the radiance of its thirty years, in the sparkle of the necklace on Catherine's royal neck, in her bare, slender legs, in her swaying, elastic breast. The teeth of the vision sparkled, and a purple shadow fell on her cheeks from her eyelashes.

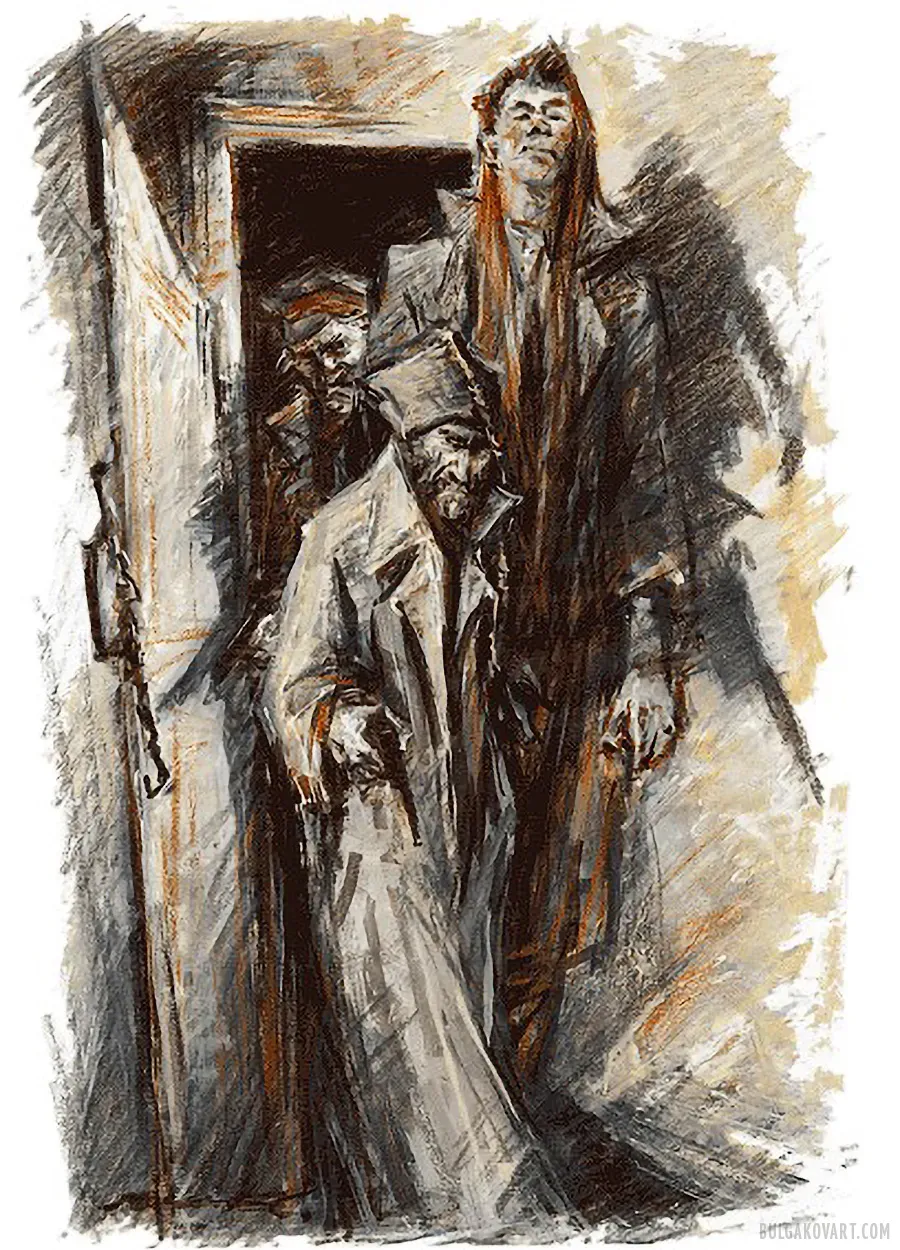

Like in a nightmare, Vasilisa moved under the pressure of those entering the doors and saw them as if in a nightmare. Everything in the first person was wolf-like; that's how it seemed to Vasilisa for some reason. The second—a giant—took up almost the entire front room of Vasilisa's house, reaching to the ceiling. He was rosy with a womanly, full, and joyful blush, young, and nothing grew on his cheeks. The third had a sunken nose, eaten away on the side by a festering scab, and a stitched and disfigured scar on his lip.

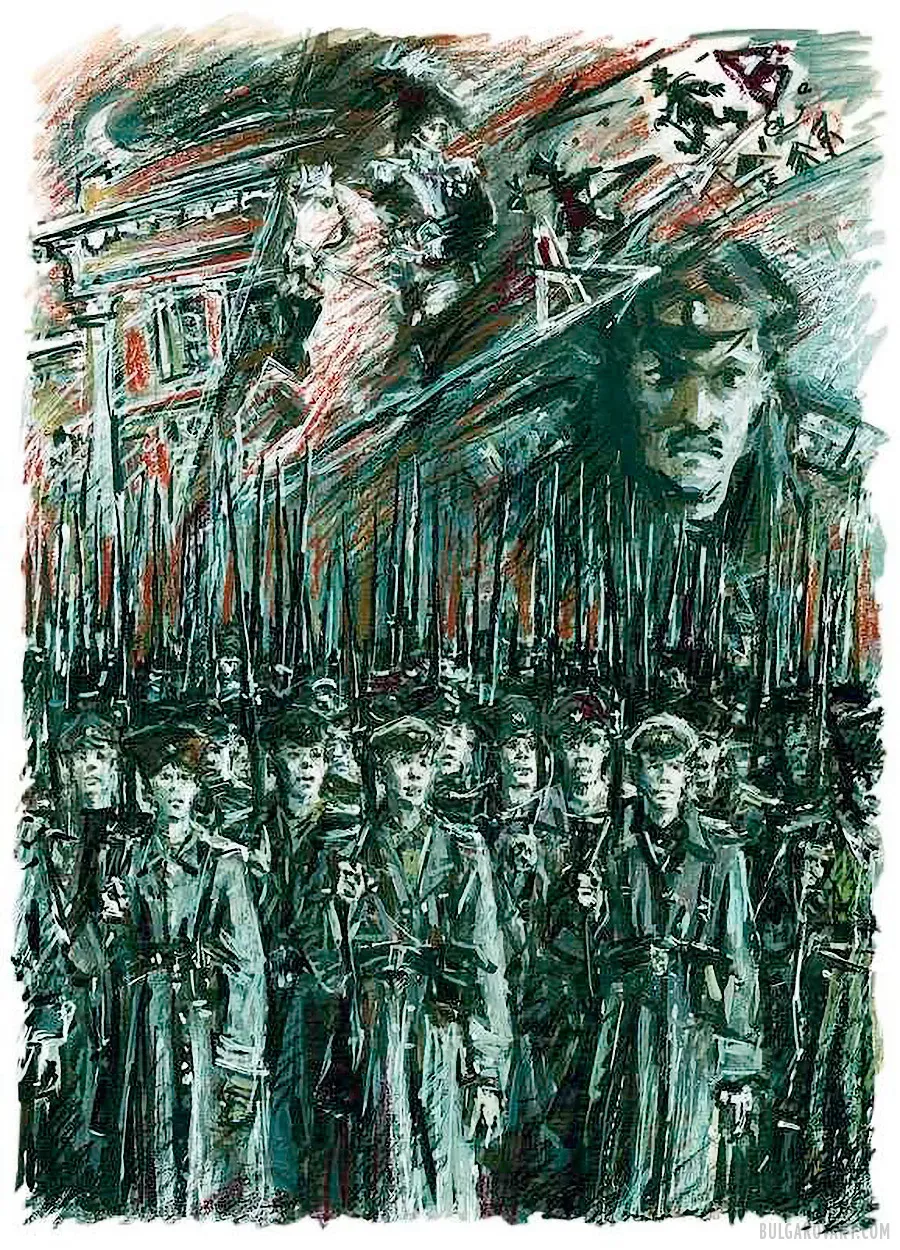

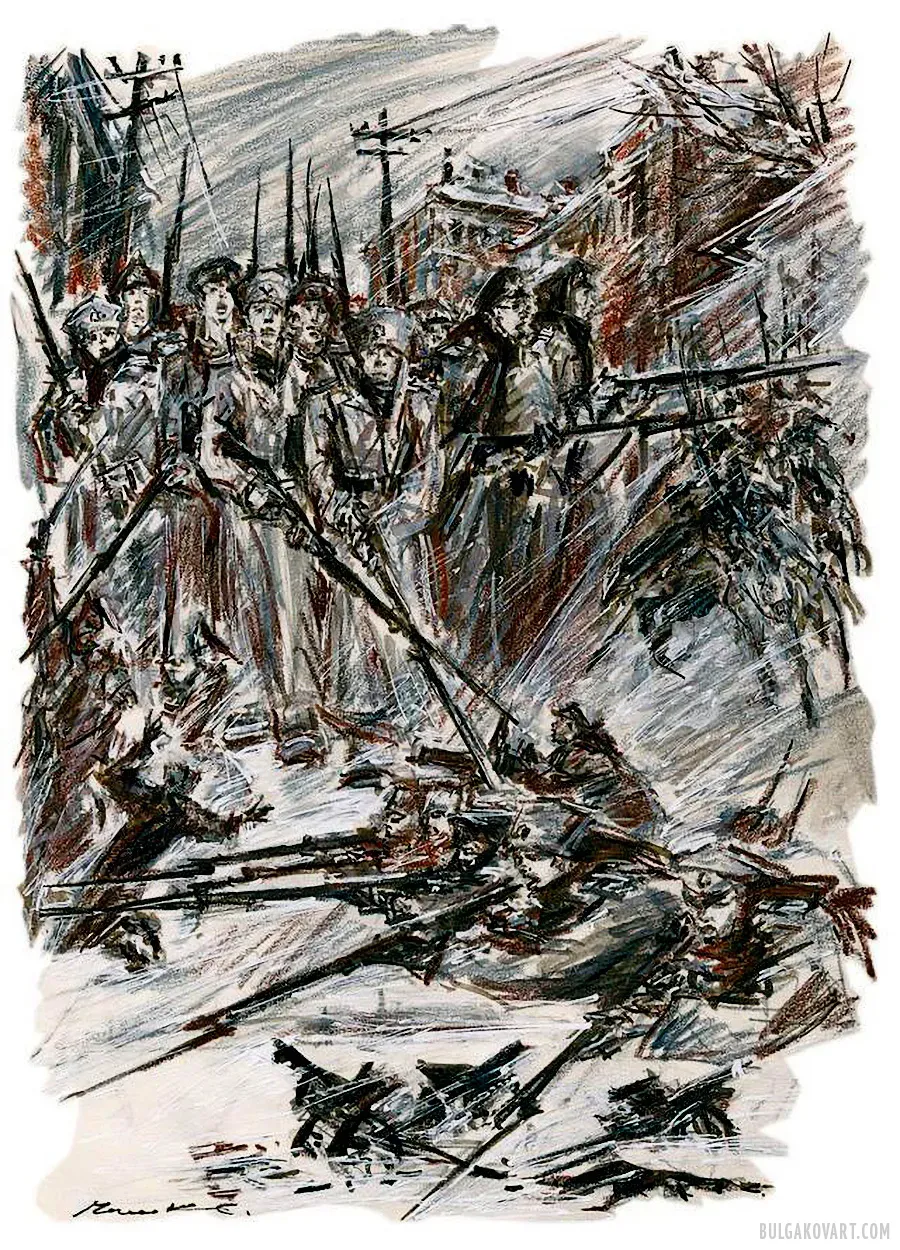

“They will fight. But they are completely inexperienced. A hundred and twenty cadets and eighty students who can't hold a rifle in their hands.”

On a purebred argamak covered with a royal saddlecloth with monograms, rearing the argamak, shining with a smile, in a tricorn hat cocked to one side, with a white plume, a balding and dazzling Alexander galloped in front of the artillerymen. Sending them smile after smile, full of treacherous charm, Alexander waved his saber and with its point indicated the Borodino regiments to the cadets. The Borodino fields were cloaked in little balls of cannonballs, and the distance on the two-yard canvas was covered by a black cloud of bayonets.

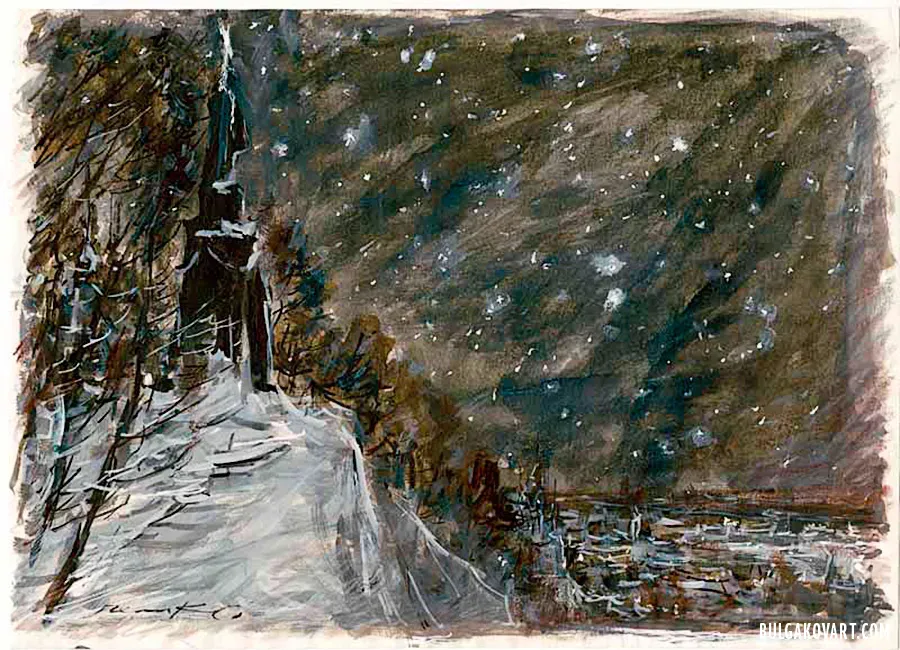

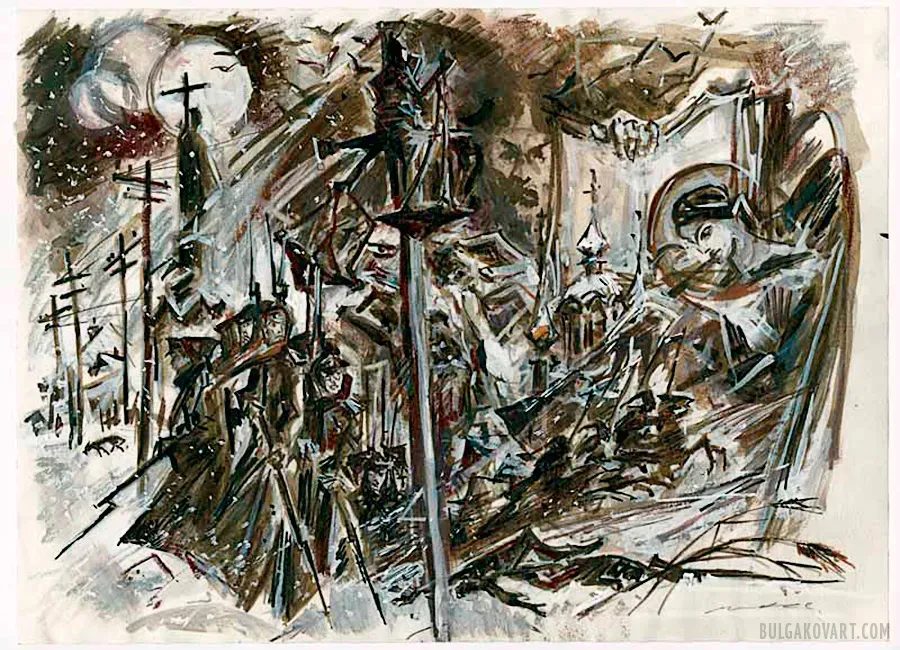

A mounted squadron, spinning in the blizzard, dashed out of the darkness from behind the lights and killed all the cadets and four officers. The commander, who remained in the dugout by the phone, shot himself in the mouth.

Two gray men, followed by a third, jumped out from behind the corner of Volodimirskaya Street, and all three flashed their weapons in rapid succession. Turbin, slowing his run, baring his teeth, shot at them three times without aiming.

The apparition was in a brown tunic, brown riding breeches, and boots with yellow jockey flaps. The eyes, muddy and sorrowful, looked out of the deepest sockets of an incredibly huge, short-clipped head. The apparition was undoubtedly young, but the skin on its face was old, grayish, and its teeth looked crooked and yellow. In the apparition's hands was a large cage with a black scarf thrown over it and an unsealed blue letter…

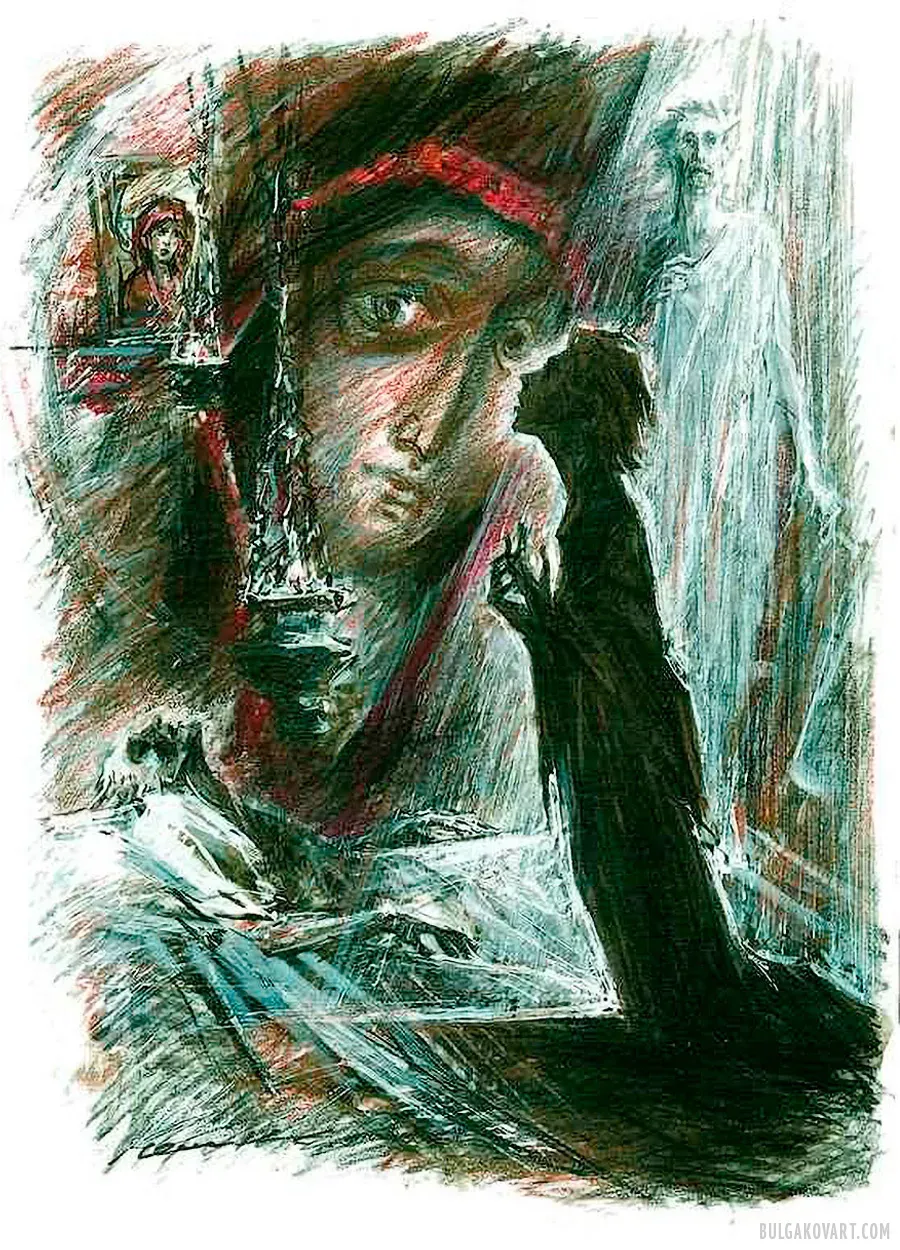

Elena more than once turned into the dark and superfluous Lariosik, Serezha's nephew, and, returning to the ginger Elena, she ran her fingers somewhere near her forehead, and it brought very little relief. Elena's hands, usually warm and deft, now moved like rakes, long and stupidly, and did all the most unnecessary, restless things that poison a peaceful person's life in the cursed military depot courtyard.

Elena, on her knees, looked up from under her brows at the jagged crown over the blackened face with clear eyes and, stretching out her hands, said in a whisper:

“My only hope is in you, most pure virgin. In you. Plead with your son, plead with the Lord God to send a miracle...”

The clatter of bolts ran through the cadet chains, Nai took out a whistle, blew it shrilly, and shouted:

“Dwectly at the cavawwy!.. volleys... fiwe!”

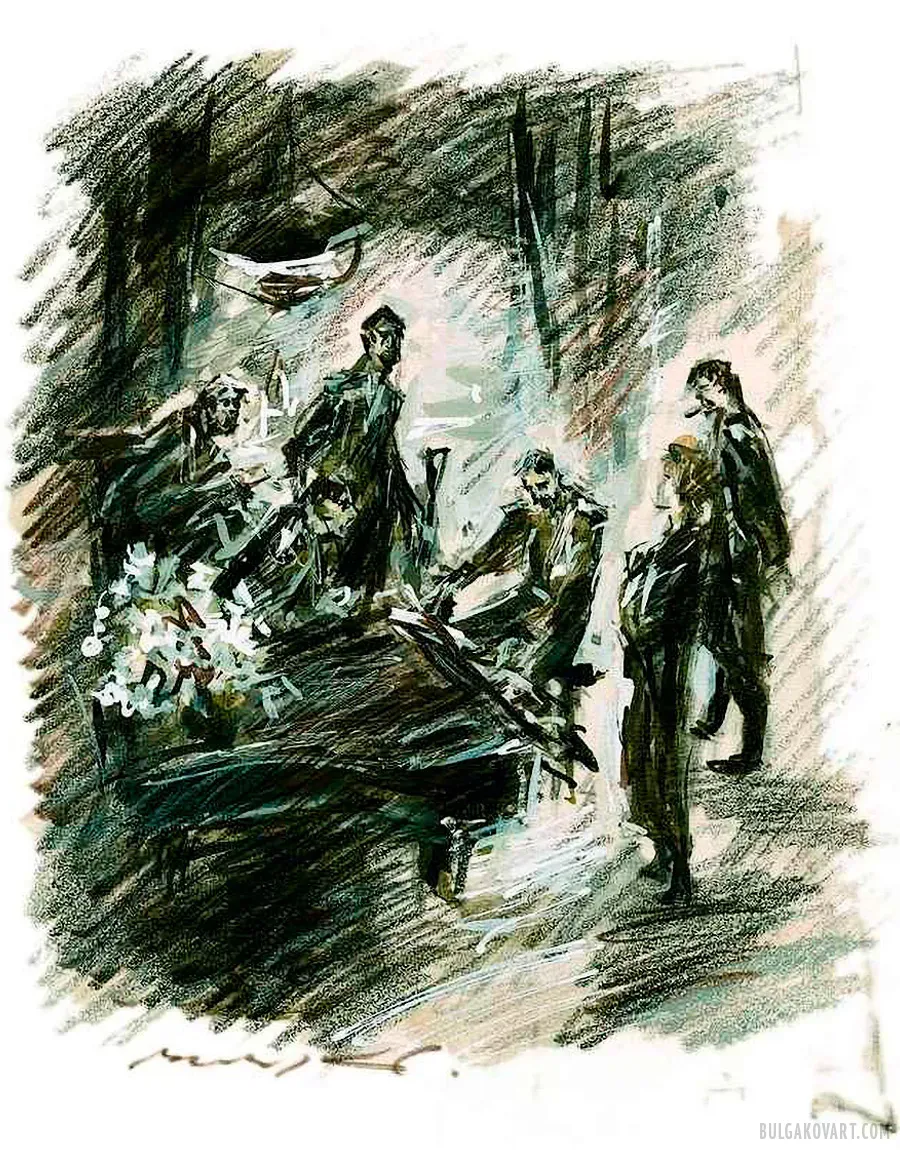

Nai—washed by the satisfied and talkative caretakers, Nai—clean, in a tunic without epaulettes, Nai with a crown on his forehead under three lights, and, most importantly, Nai with a yard of colorful St. George's ribbon, personally placed by Nikolka under his shirt on his cold, sticky chest. The old mother turned her trembling head from the three lights toward Nikolka and said to him, "My son. Thank you."

No, you will suffocate in such a country and at such a time. To the devil with it! A myth. Petliura is a myth. He didn't exist at all. It's a myth, as remarkable as the myth of the never-existent Napoleon, but far less beautiful. Something else happened. This very peasant's wrath needed to be lured along some single road, for it is arranged so magically in this world that no matter how far he runs, he always fatally ends up at the same crossroads. It's very simple. Just have a riot, and people will be found.

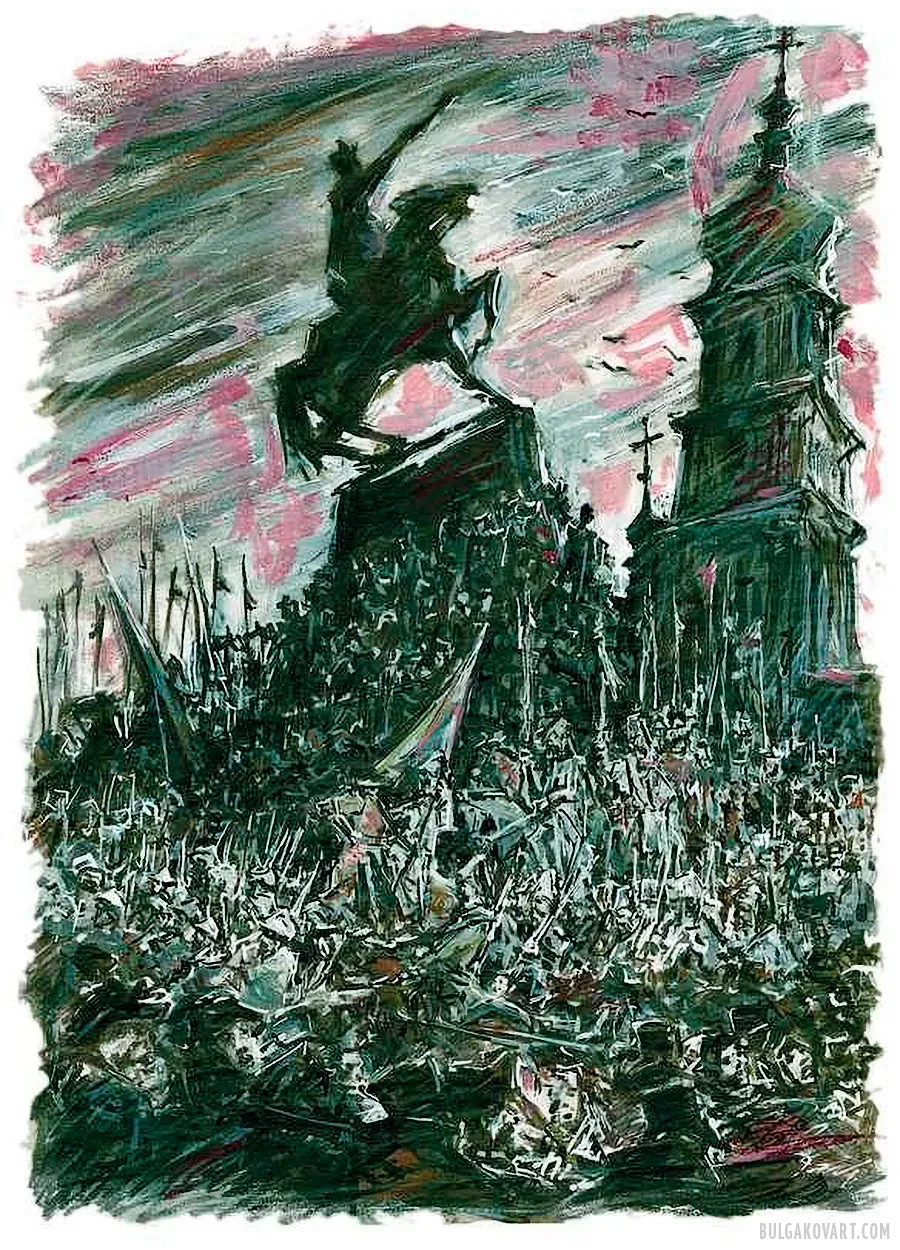

The galloping Bogdan Khmelnitsky furiously tore the horse from the cliff, trying to fly away from those who hung heavily on his hooves. His face, turned directly into the red ball, was furious, and he still pointed his mace into the distance.

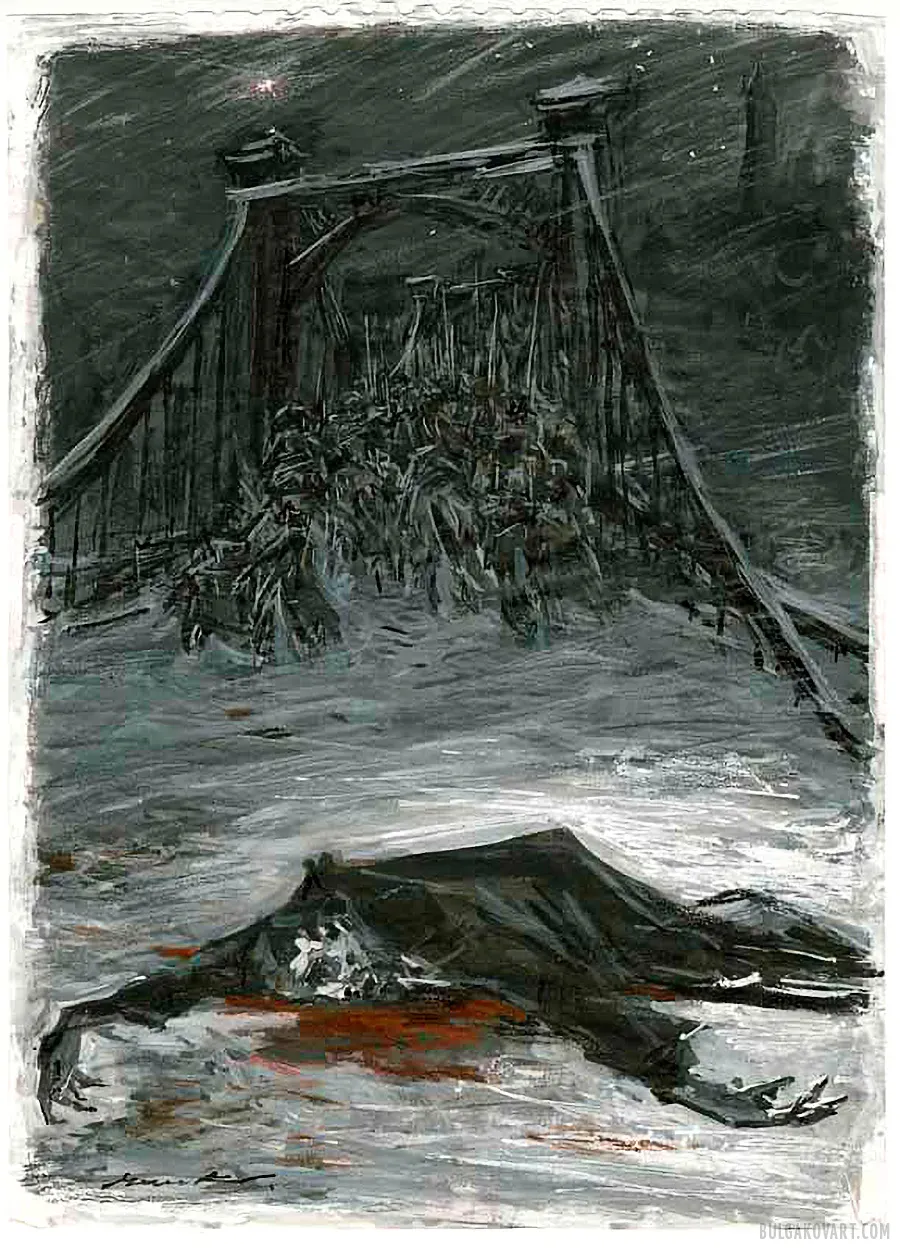

Then everything disappeared as if it had never existed. Only the cooling corpse of the Jew in black remained at the entrance to the bridge, along with the trodden clumps of hay and horse manure. And only the corpse testified that Petliura was not a myth, that he truly was…

Above the Dnieper, from the sinful and bloodstained and snowy earth, the midnight cross of Vladimir rose into the black, gloomy height. From a distance, it seemed that the horizontal crossbar had disappeared—merged with the vertical—and because of this, the cross turned into a menacing sharp sword.