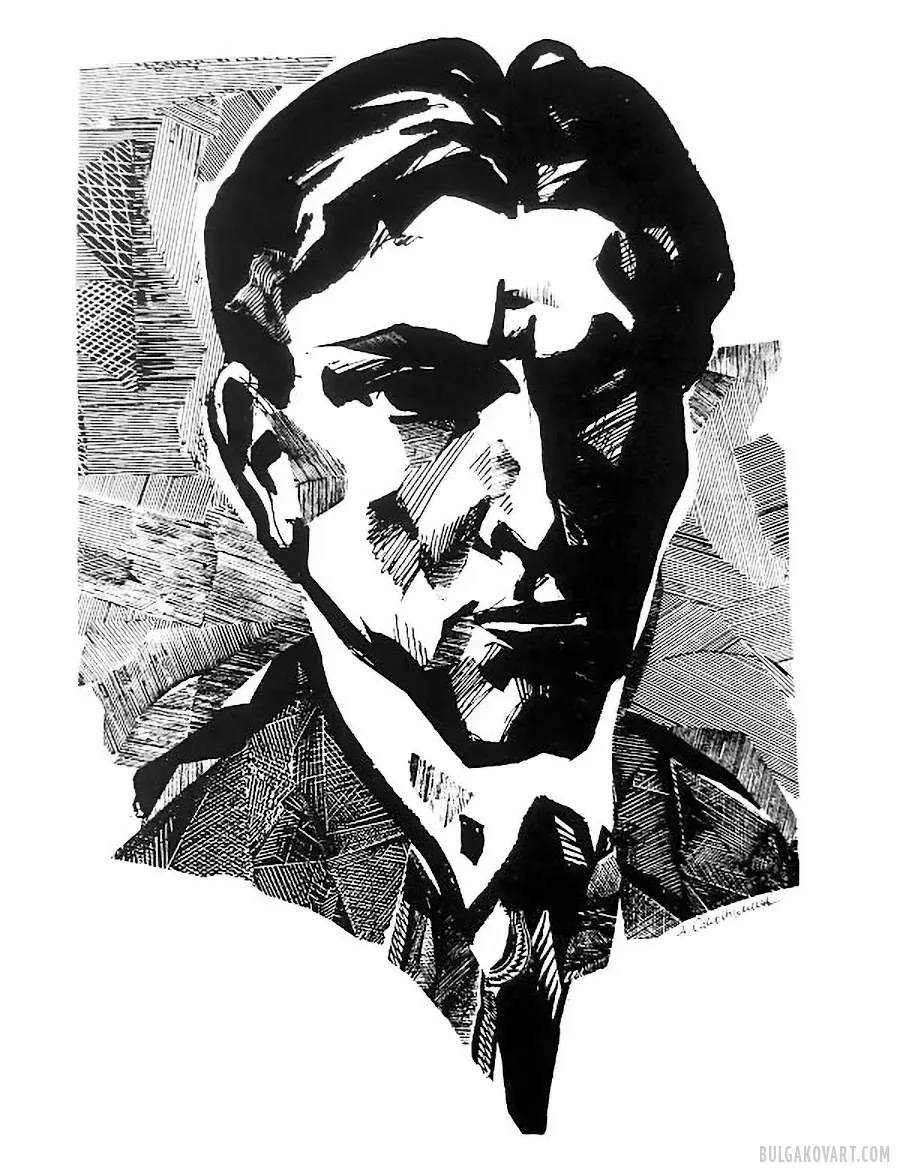

Alexander Sapozhnikov (1925 – 2009) was an outstanding graphic artist and book illustrator who created artwork for more than two hundred titles. In 2001 he completed a cycle of etchings for The Master and Margarita.

(Many thanks to Alexander Sobinov for sharing the images.)

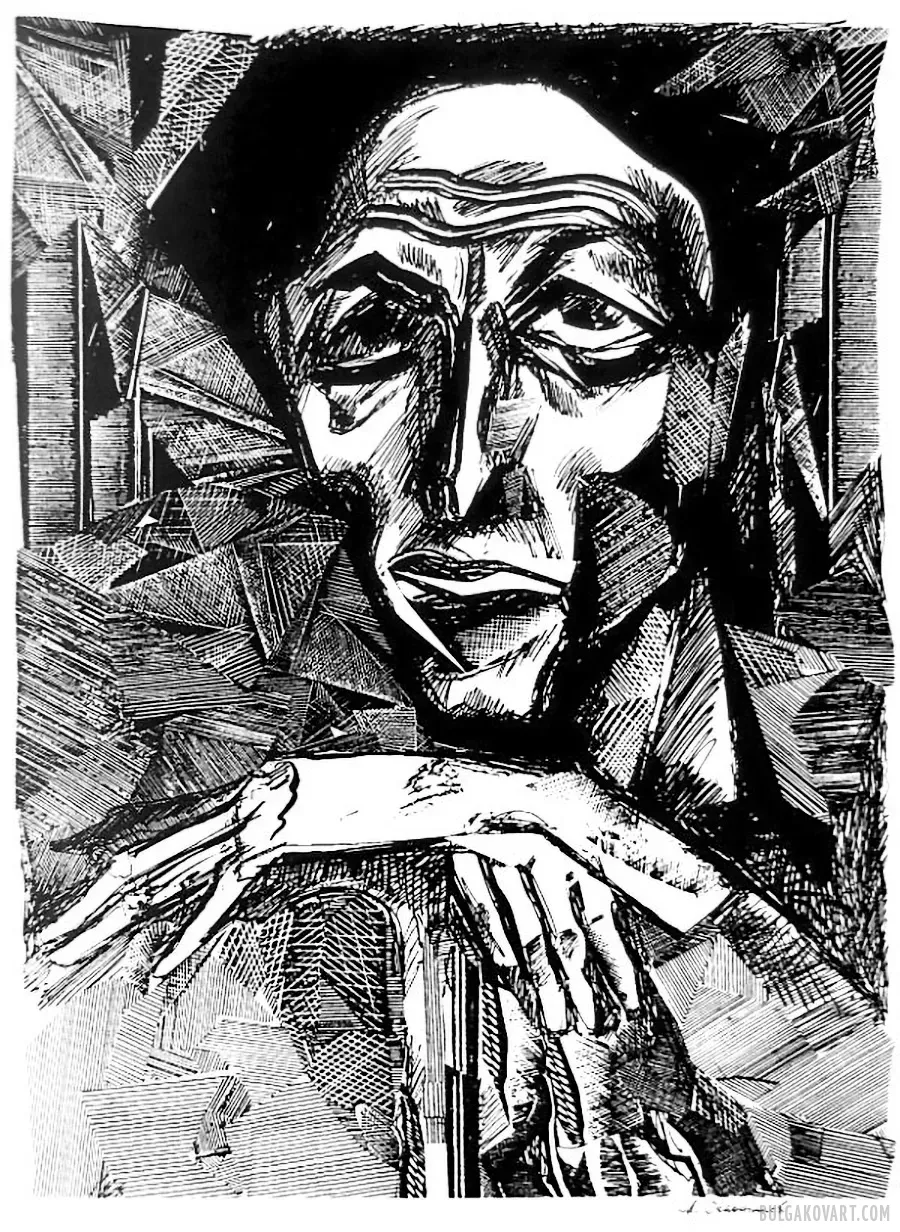

“We have to judge a man in the fullness of his being—man as man—even if he is sinful, objectionable, embittered, or arrogant. One must seek the core, the deepest human essence in that person.”

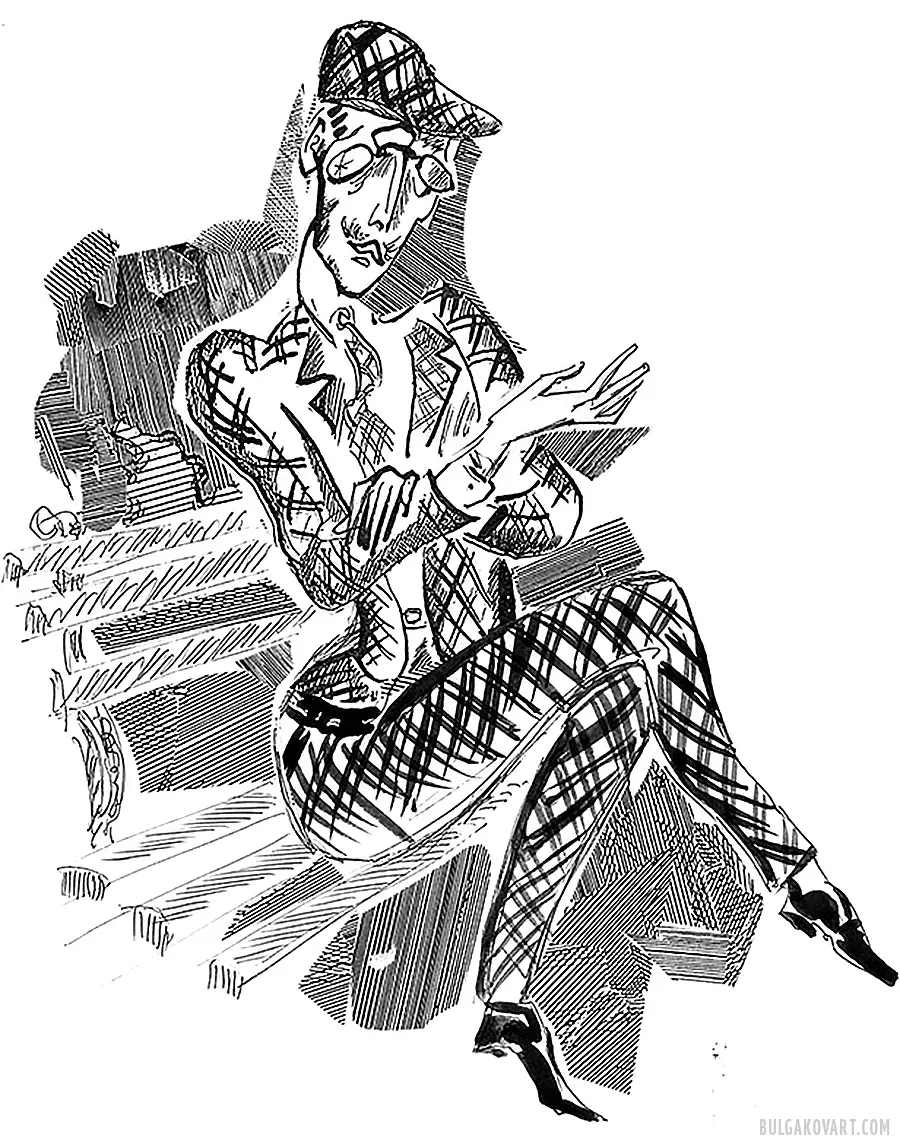

“So who are you, then, after all?”

“I am part of that power which always wills evil, and always brings forth good.”

He grinned, squinted, placed his hands on the knob, and his chin on his hands.

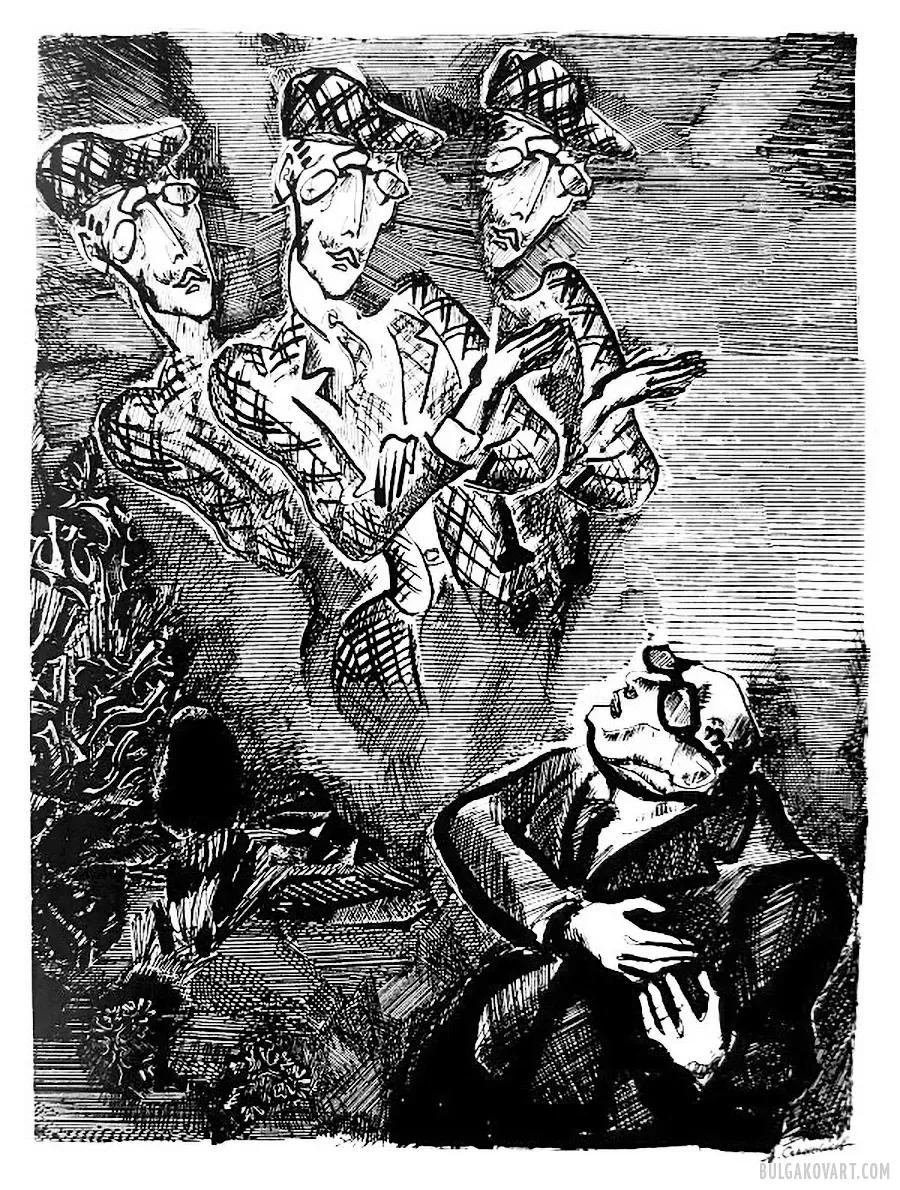

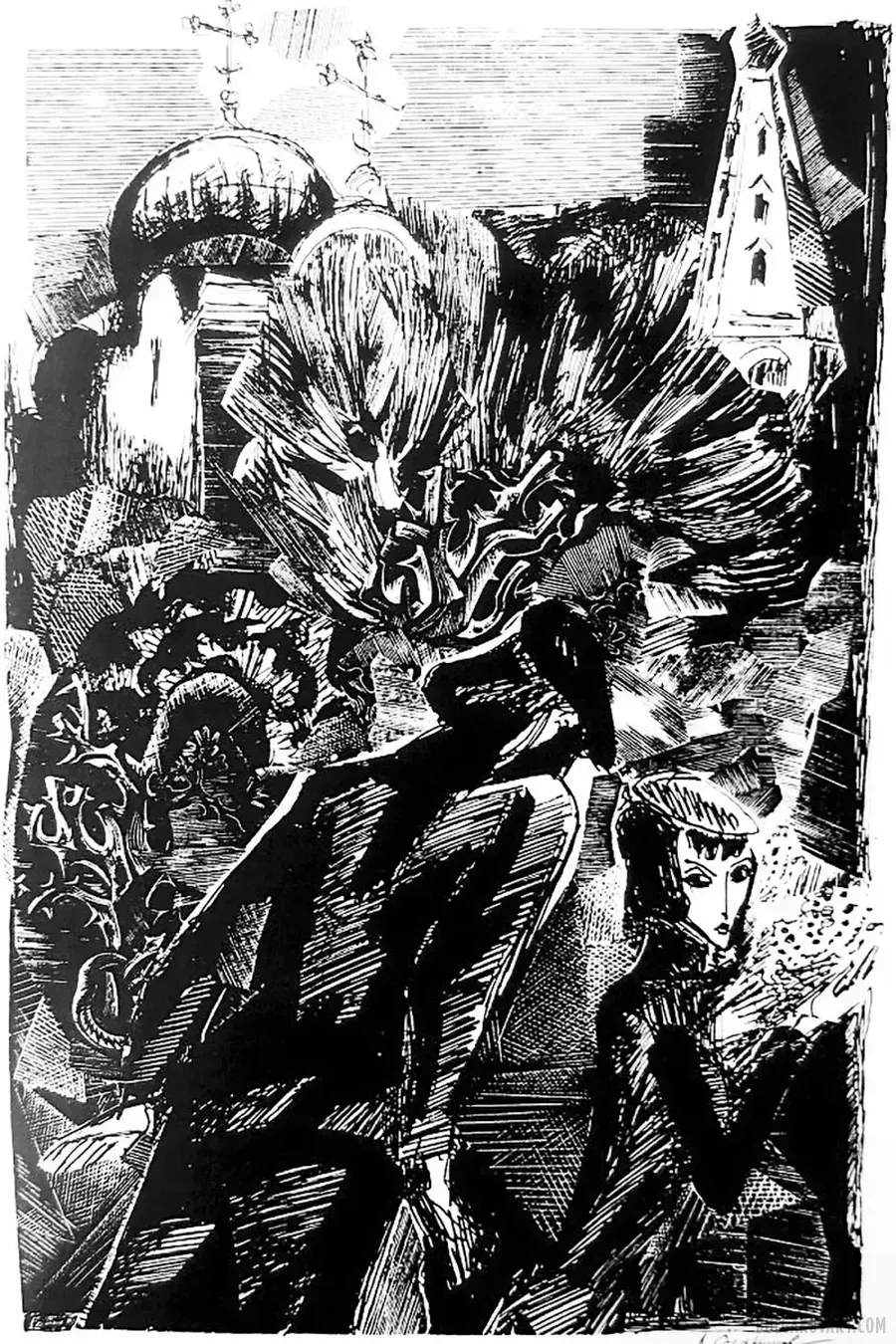

Then the torrid air thickened before him, and out of it wove a transparent citizen of the strangest appearance.

Near the Bronnaya exit the very same citizen who had been molded from the greasy heat in the sunlight rose from a bench to meet the editor.

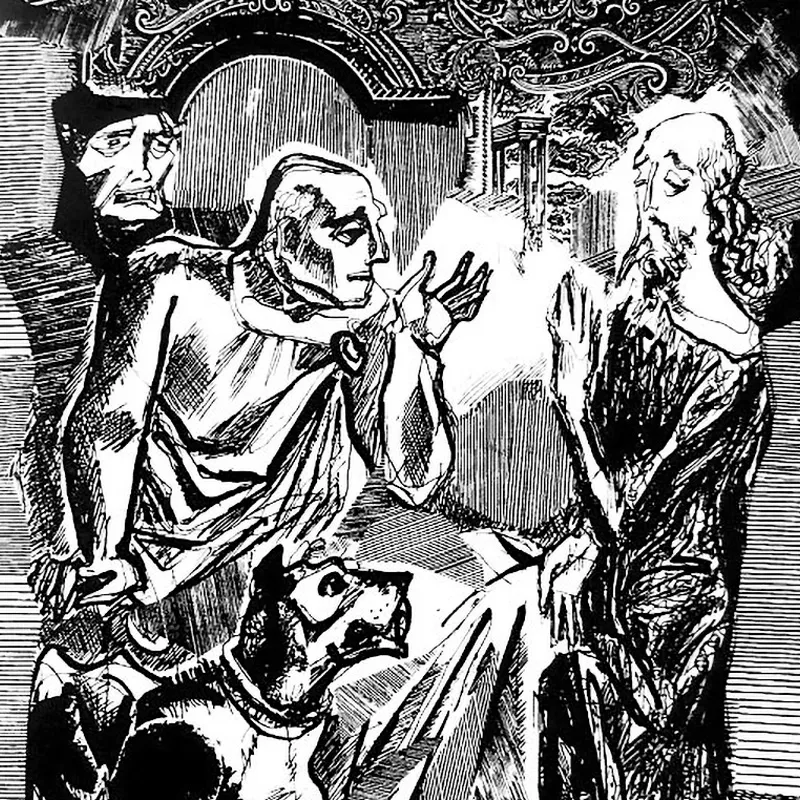

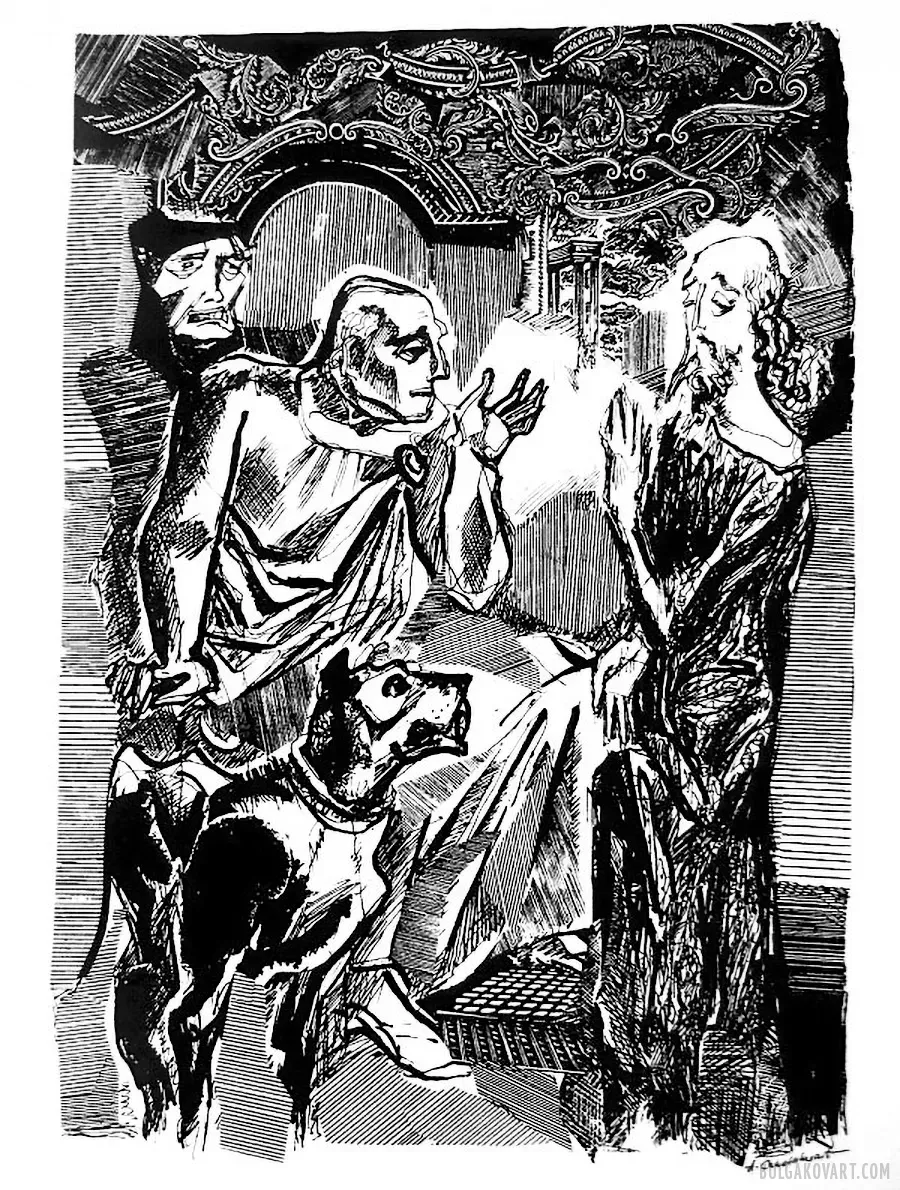

“Why did you, vagabond, disturb the crowd in the market, babbling about truth when you have no notion of it? What is truth?”

“Annushka has already bought the sunflower oil—and not only bought it, she has even spilled it. So the meeting will not take place.”

“Greetings, friends!”

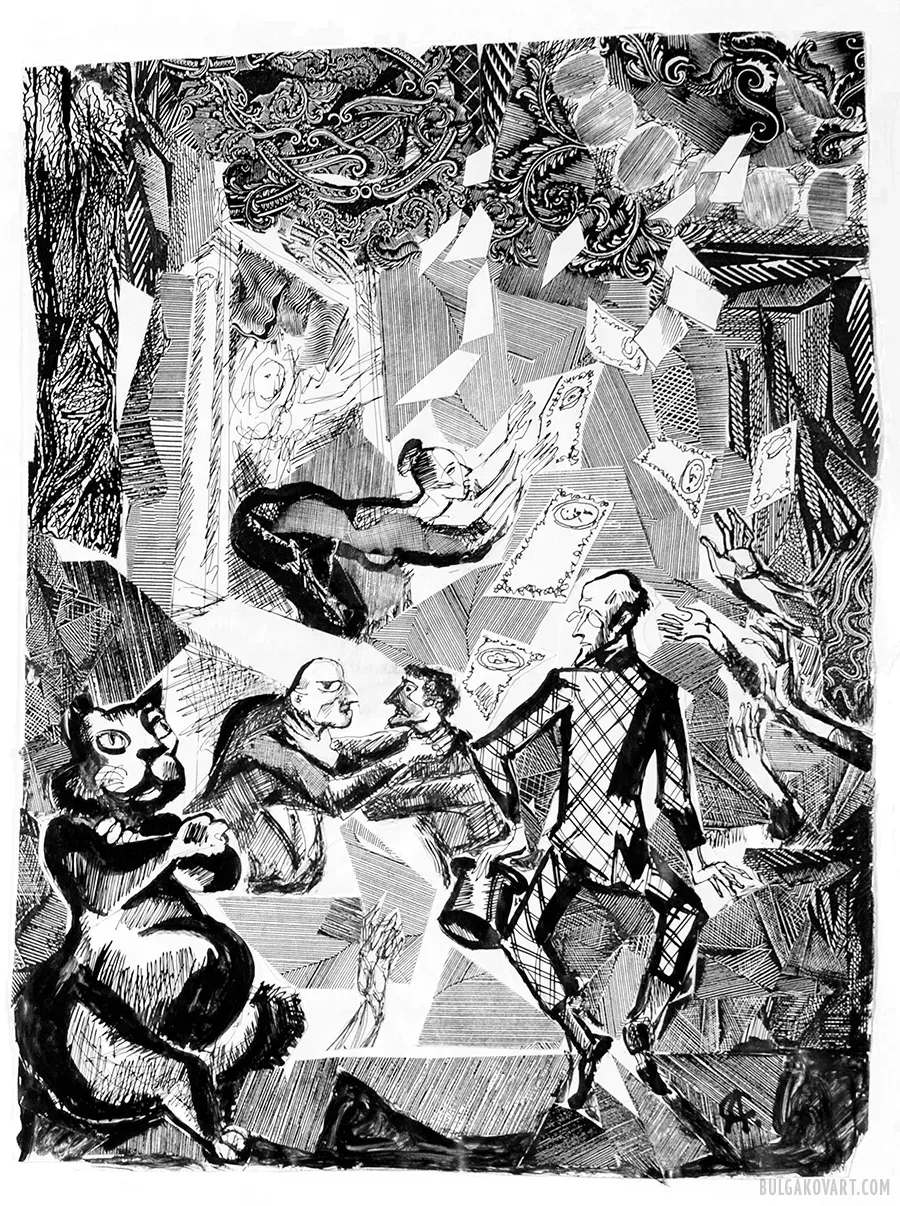

A gigantic black cat, a stack of vodka glasses in one paw and, in the other, a fork skewering a pickled mushroom.

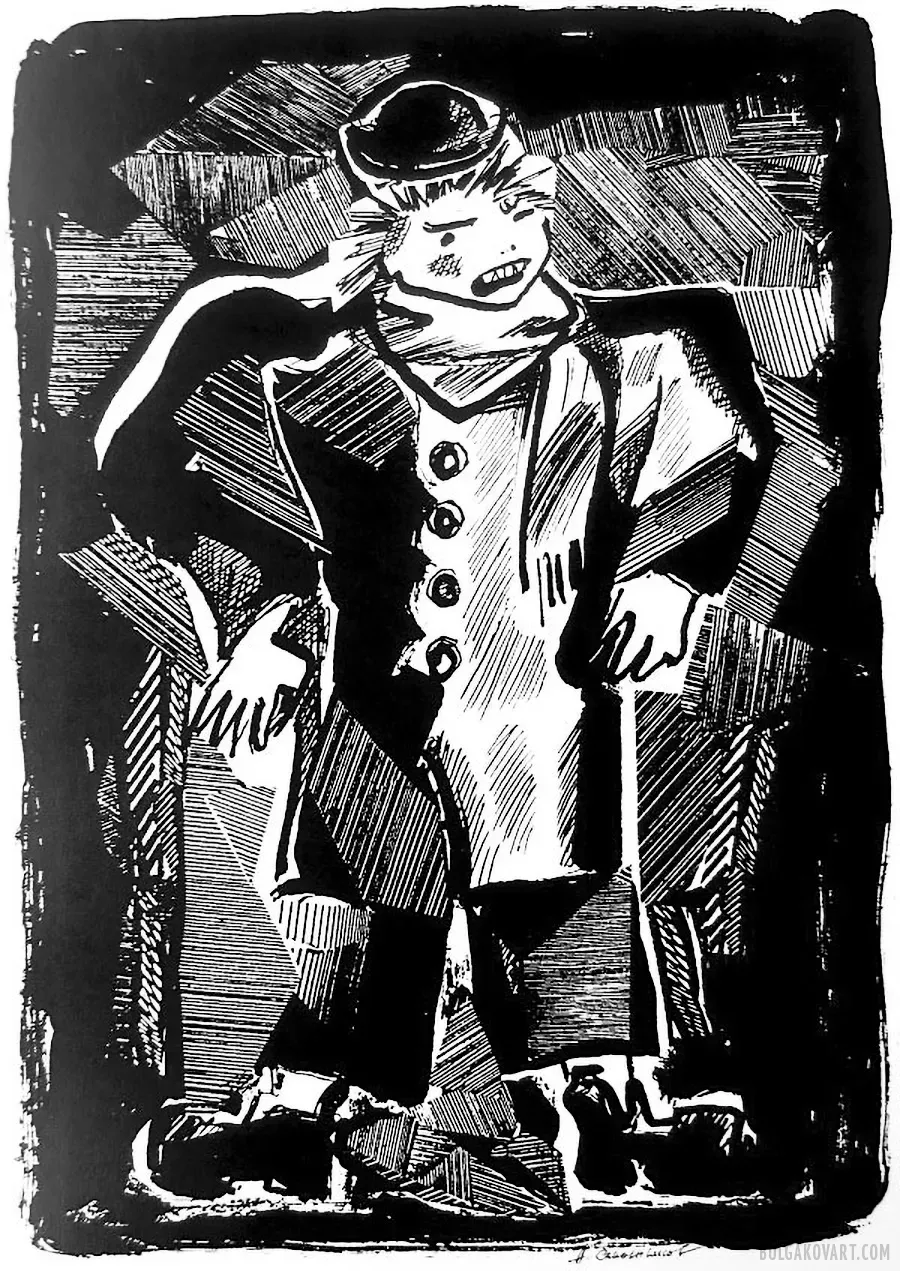

Straight out of the trumeau mirror stepped a small but extraordinarily broad‑shouldered fellow in a bowler hat, a fang jutting from his mouth and disfiguring an already hideous face—his hair flaming red.

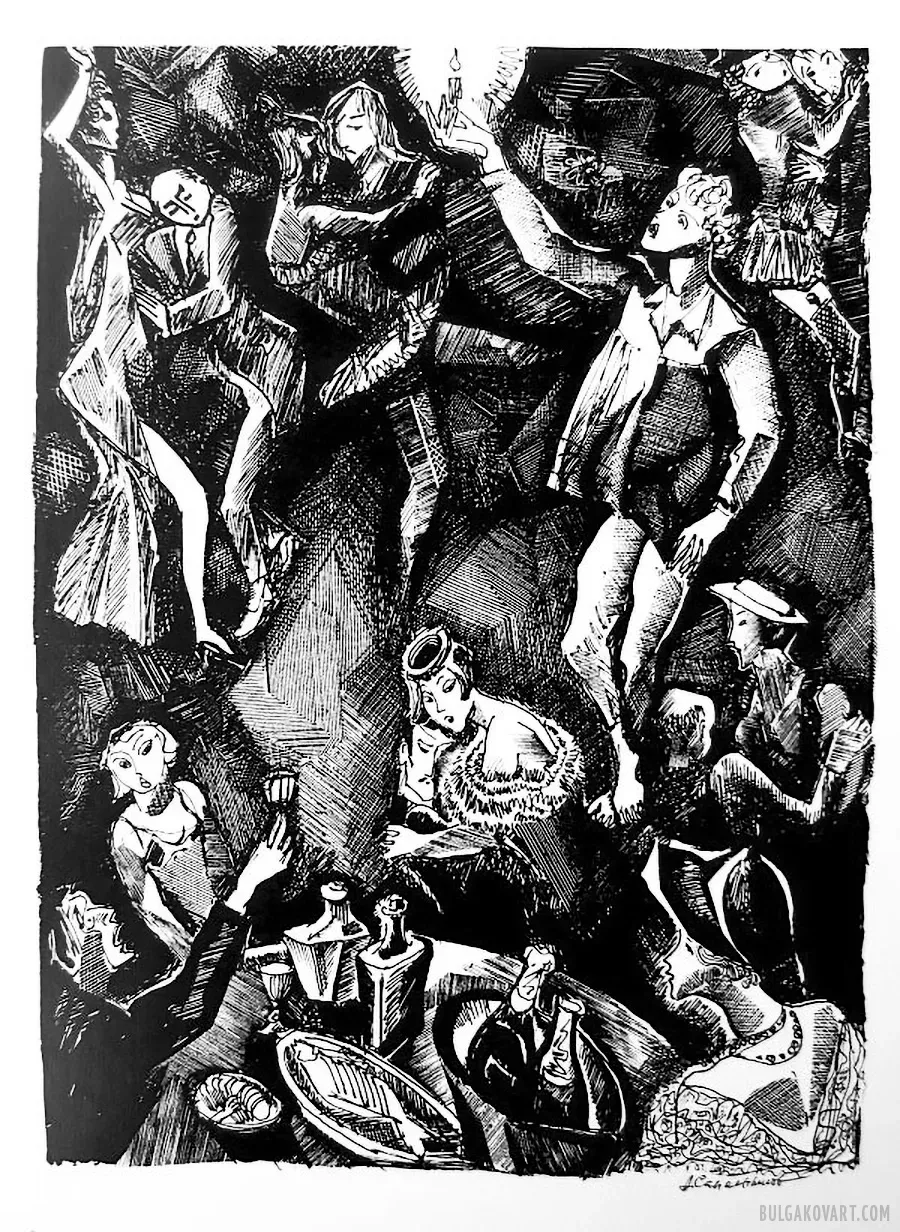

From beneath the dome, white bills began to fall into the hall, diving between the trapezes. They spun, scattered, and smashed into the gallery, smashed into the orchestra, and then onto the stage. Within seconds, the increasingly thick rain of money reached the seats, and the audience began to catch them.

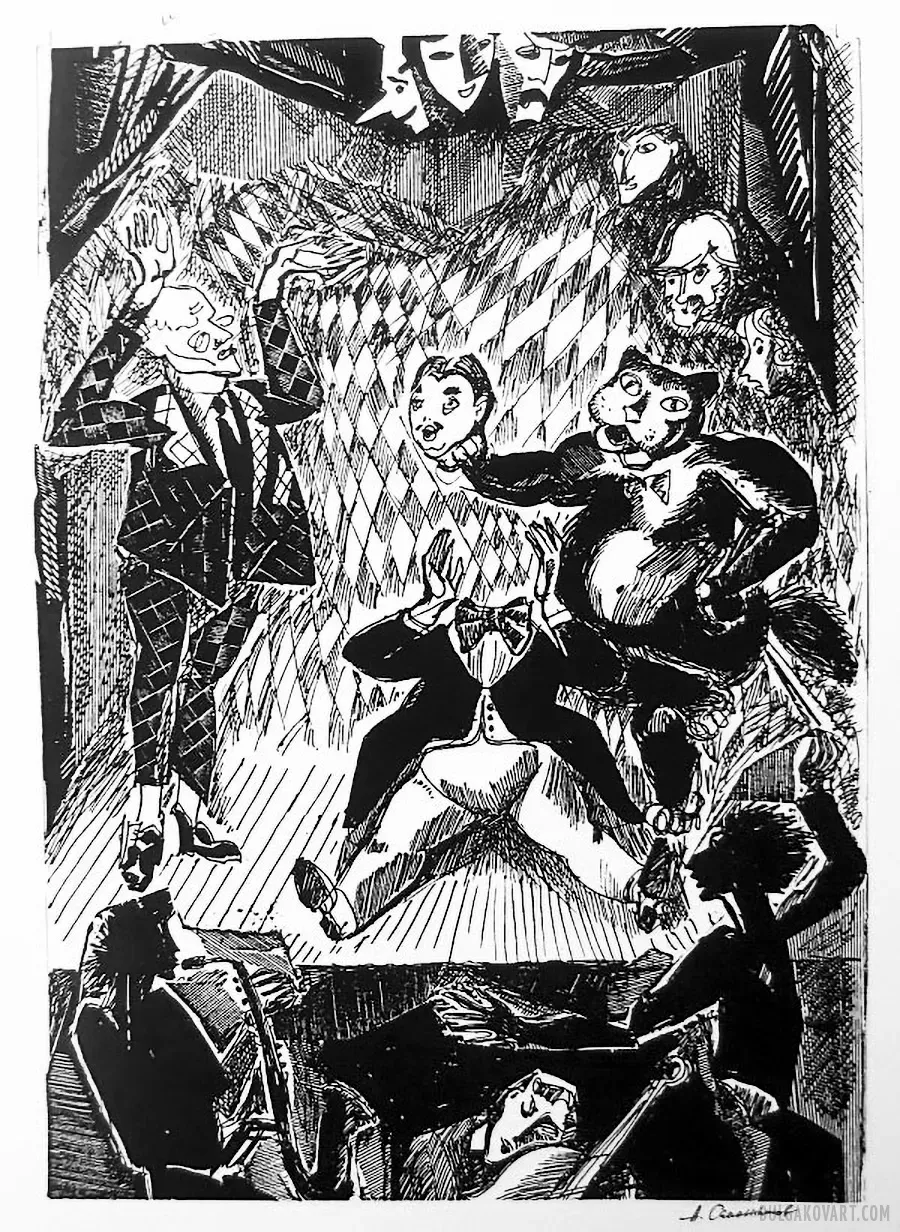

Purring, the plump‑pawed cat seized the emcee’s thin hair and, with a savage howl, twisted twice and tore the head from the stout neck.

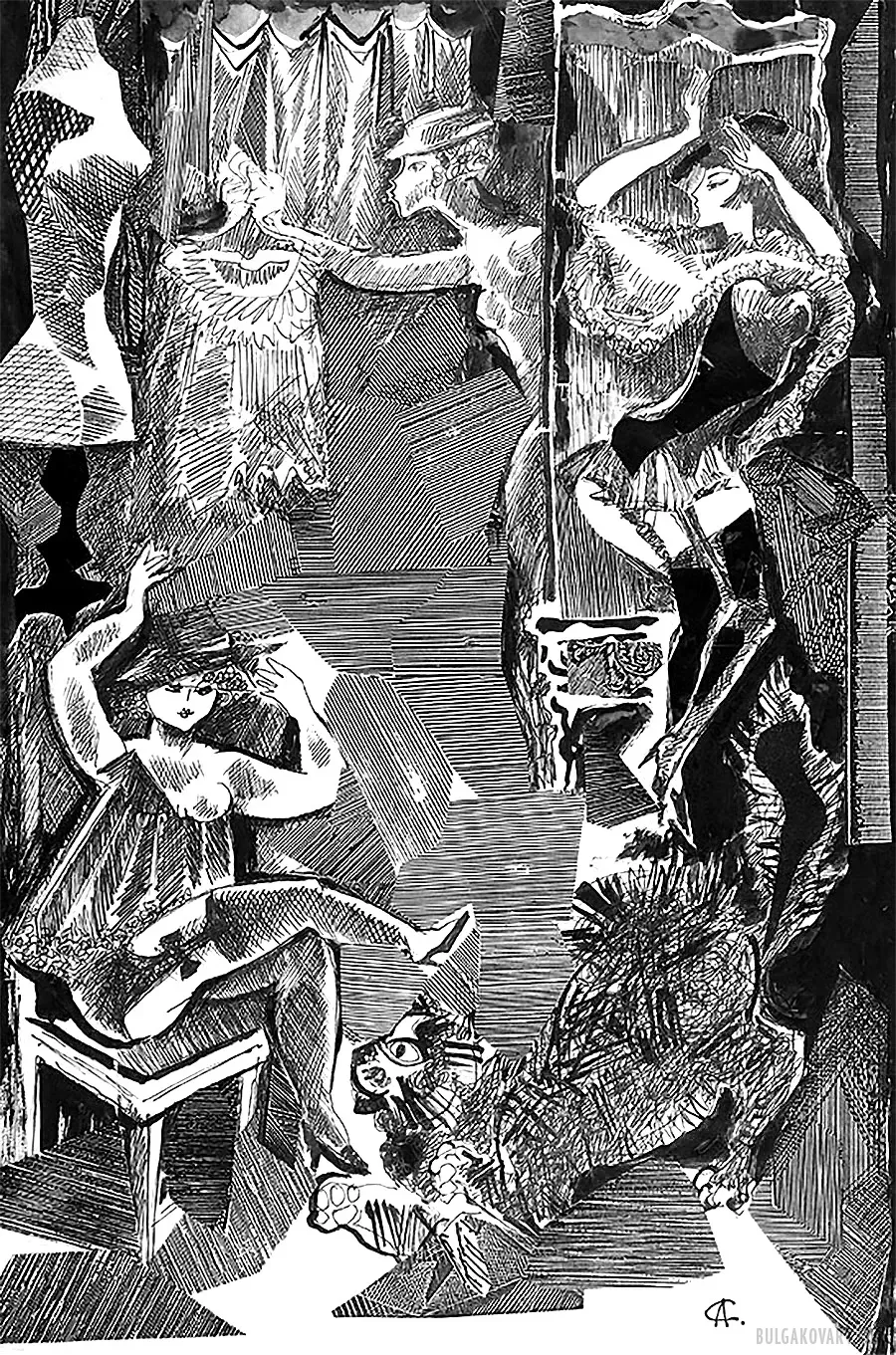

A whole row of ladies sat on gilded-legged stools, energetically stamping their newly shod feet on the carpet.

In the harsh glow of the streetlamps he saw, far below on the sidewalk, a lady in nothing but a shift and violet pantaloons. She did, however, have a hat on her head and an umbrella in her hands.

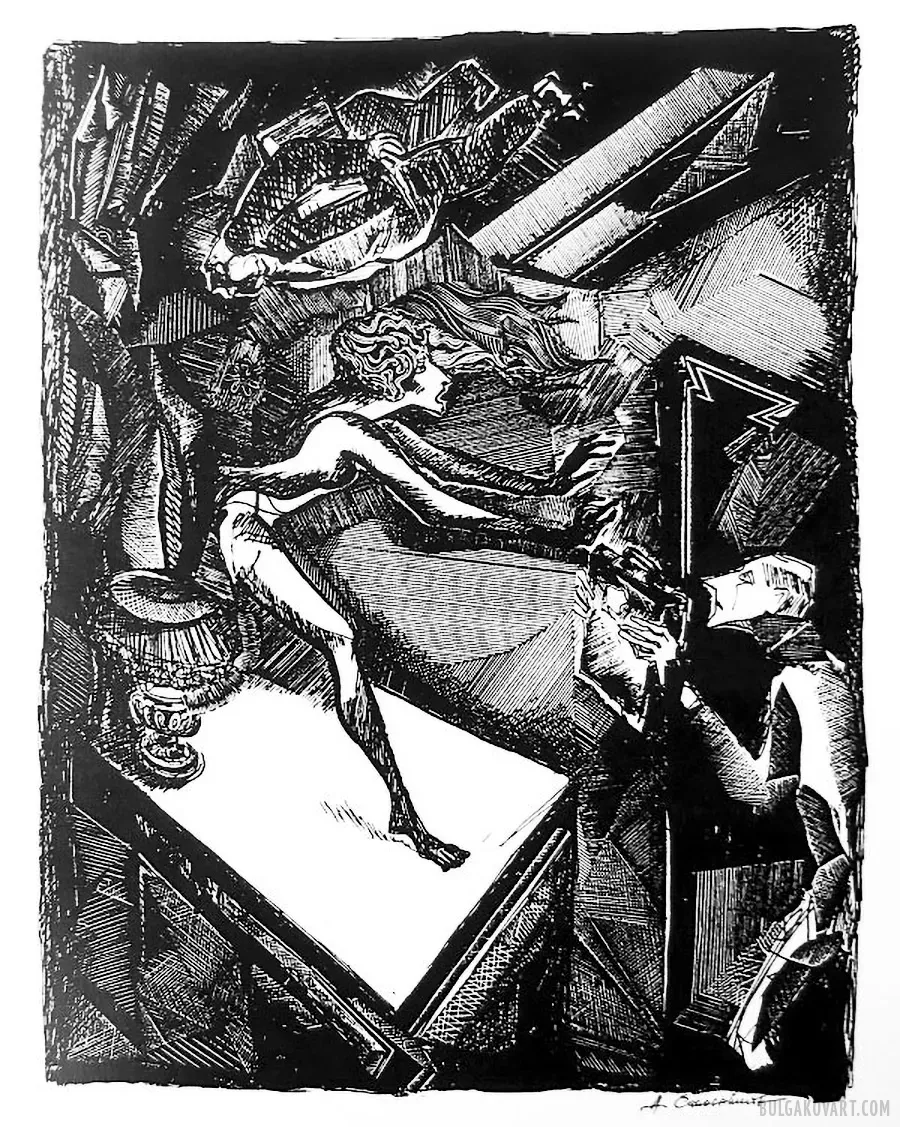

The window frame flew wide, and instead of night air and linden fragrance a cellar stench burst into the room. The dead woman stepped onto the sill; Rimsky clearly saw patches of decay on her chest

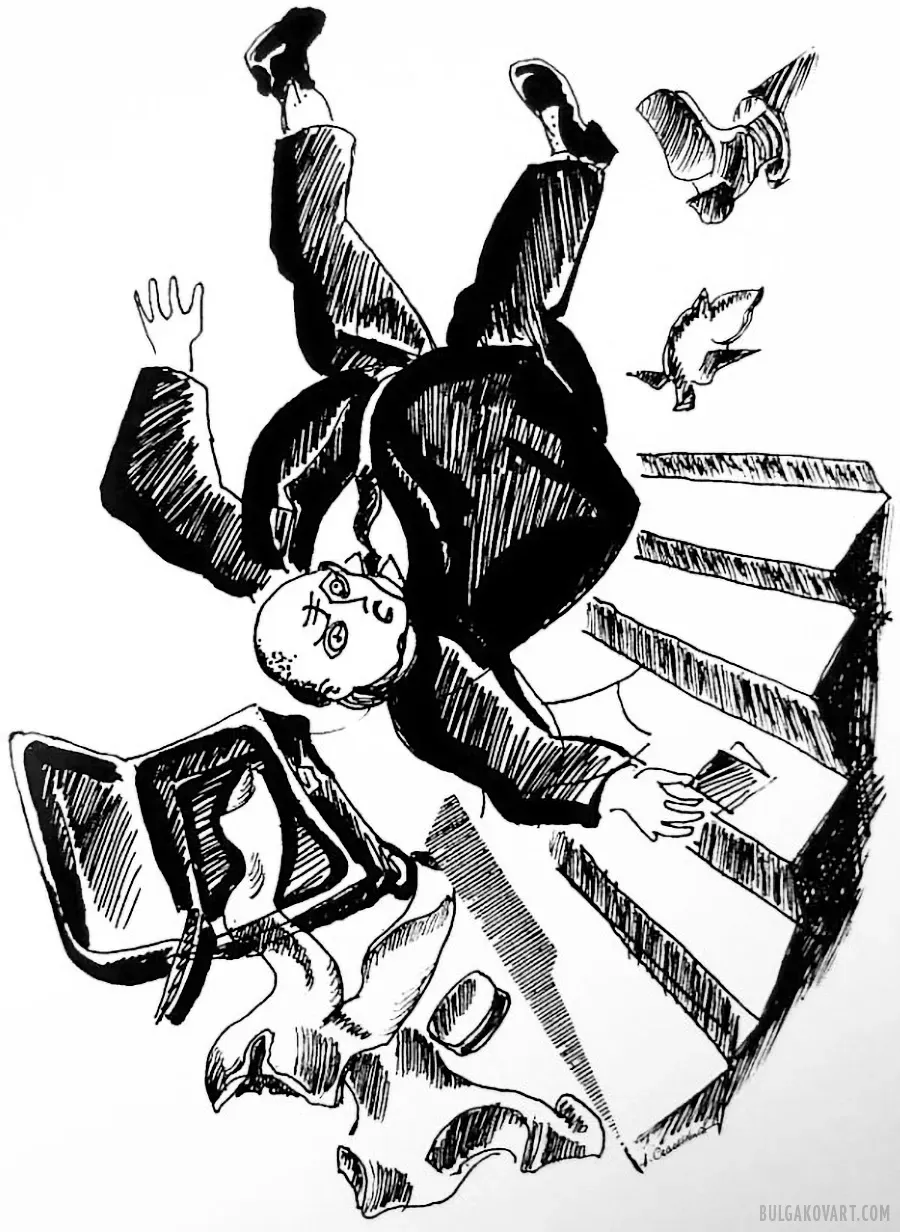

Poplavsky hurtled down the staircase, passport clutched in his hand.

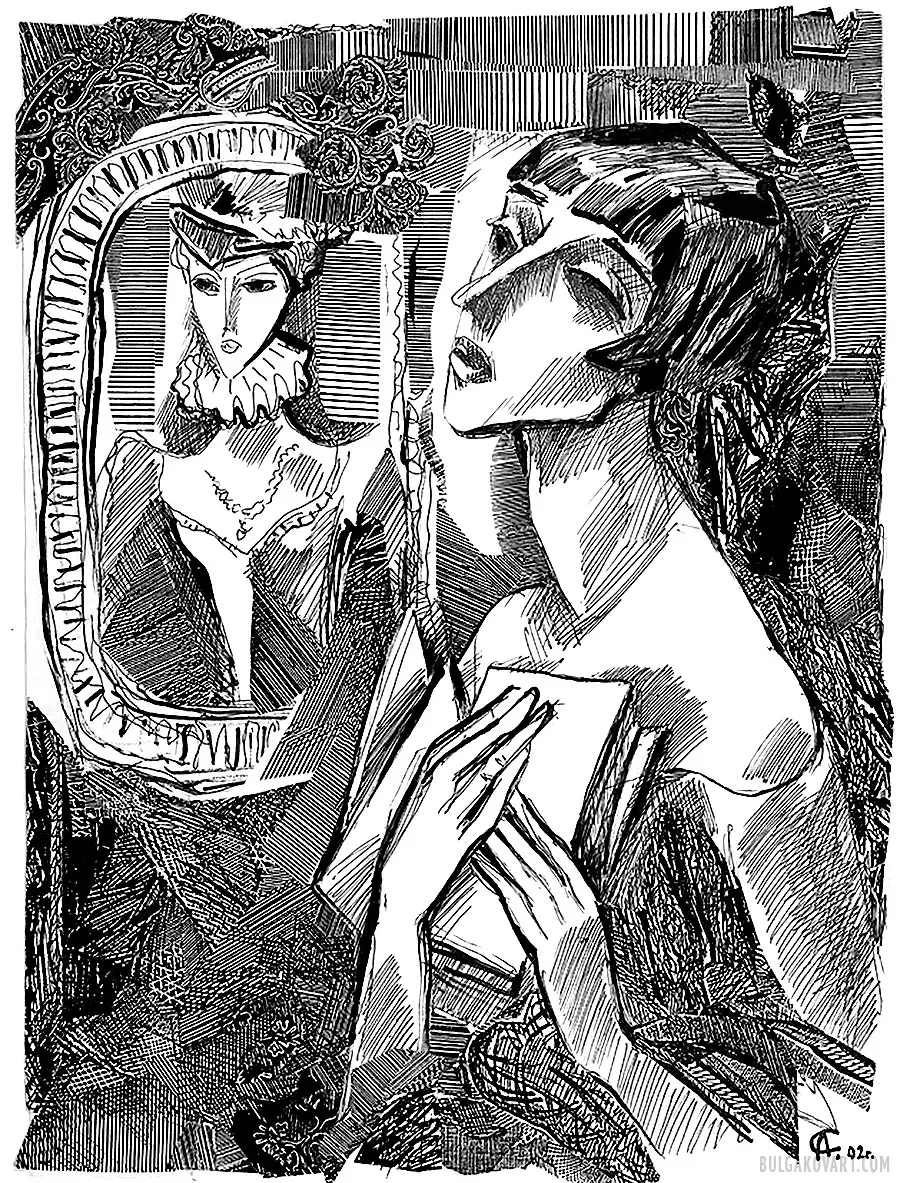

“She carried in her hands those repulsive, unsettling yellow flowers.”

“Do you like my flowers?”

“What a chambermaid that foreigner keeps! Ugh, what filth!”

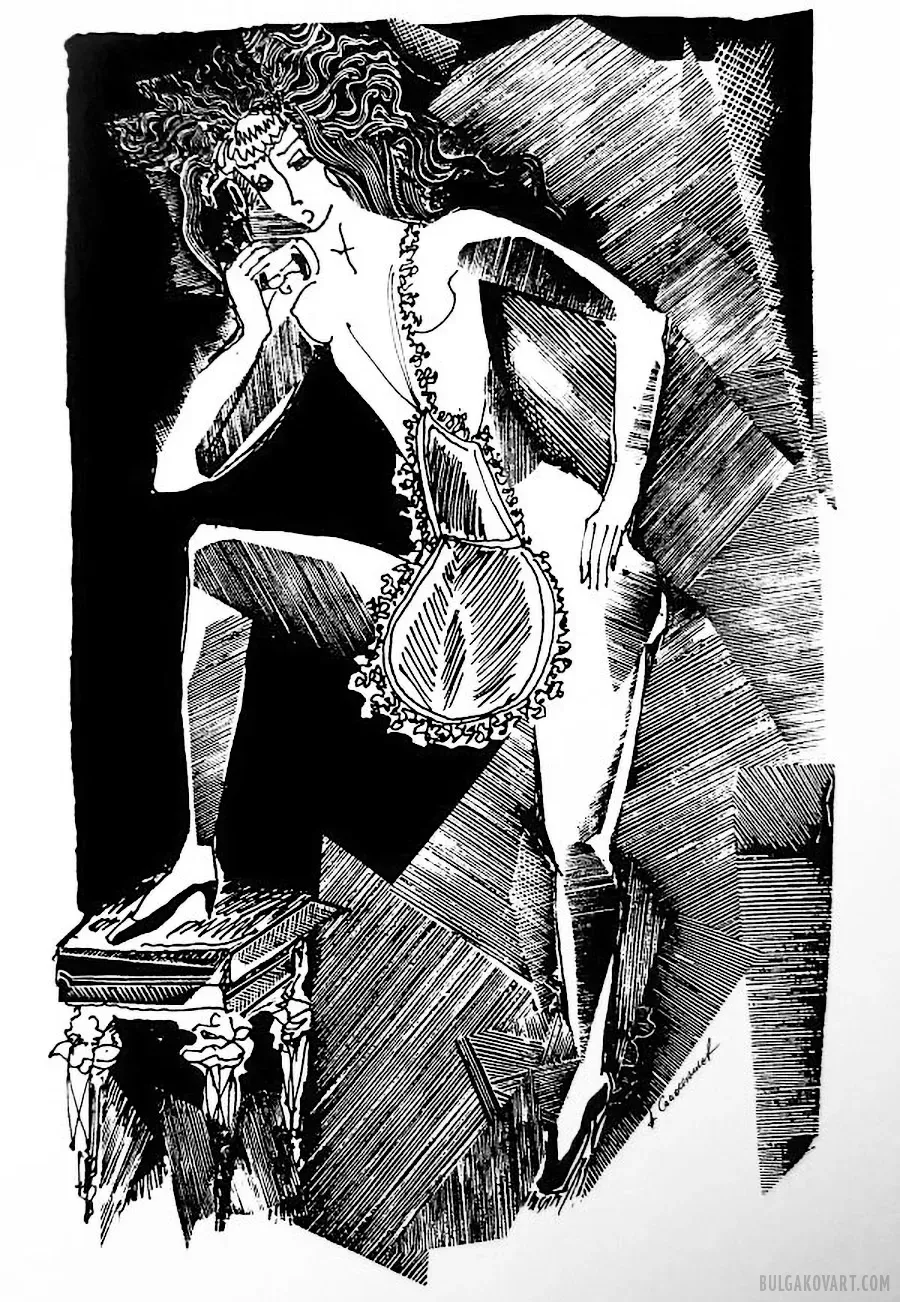

Margarita Nikolaevna sat for about an hour, holding the fire-ravaged notebook on her lap, leafing through it and rereading what, after the burning, had neither beginning nor end.

One of the French queens of the sixteenth century would probably have been very surprised if someone had told her that, many years later, I would be leading her lovely great-great-great-granddaughter by the arm through Moscow ballrooms.