The photographer and visual artist Elena Martynyuk—long a favorite of the Bulgakov House museum—is a decorated master of staged photography.

In 2000 the London Yearbook named her one of the five most intriguing photo‑artists in the world, and that same year she became the first photographer (and the only woman from Eastern Europe) to win the Super‑Circle Hasselblad prize, sometimes dubbed a photographic Oscar. Whether or not awards matter, her work is undeniably striking.

What follows is only a fraction of her Bulgakov series—after all, she staged more than seventy shoots. If you are ever in Moscow, drop by the Bulgakov House; you may be lucky enough to catch one of her exhibitions. For now, enjoy the images that are available online.

“…So who are you, then, after all?”

“I am part of that power which ever wills evil and ever works the good.”(Woland—Yuri Vasiliev; Koroviev—Denis Kurochka)

“May I sit down?” the foreigner asked politely, and the two friends somehow moved apart without meaning to. He slipped deftly between them and at once joined the conversation.

(Woland here is played by Aleksandr Shirvindt)

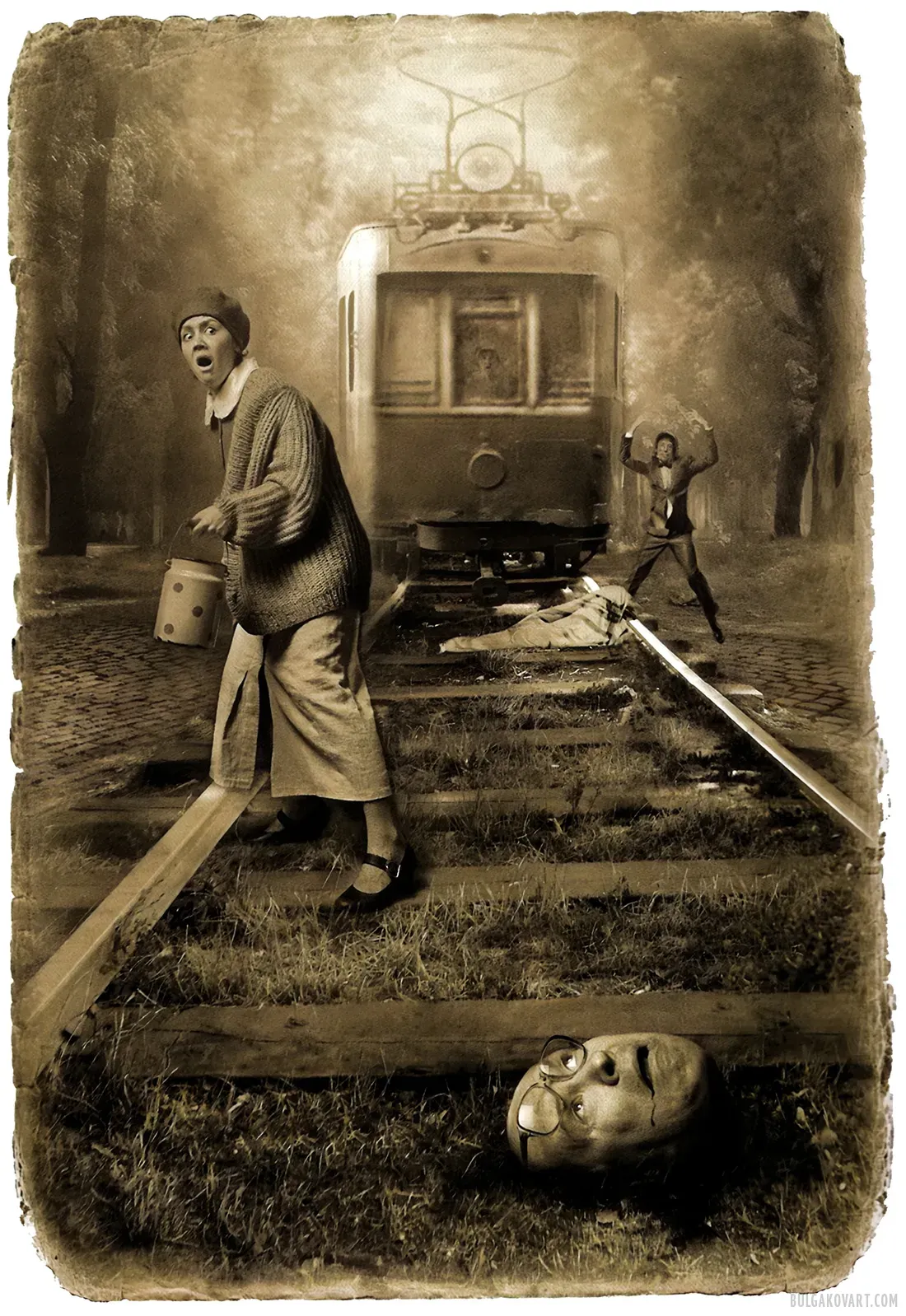

“Annushka—our Annushka from Sadovaya! It’s her doing! She bought a bottle of sunflower oil at the grocer’s, smashed the liter bottle on the turnstile, ruined her skirt… She cursed and cursed! And the poor fellow, you see, slipped on it and went straight under the tram rails…”

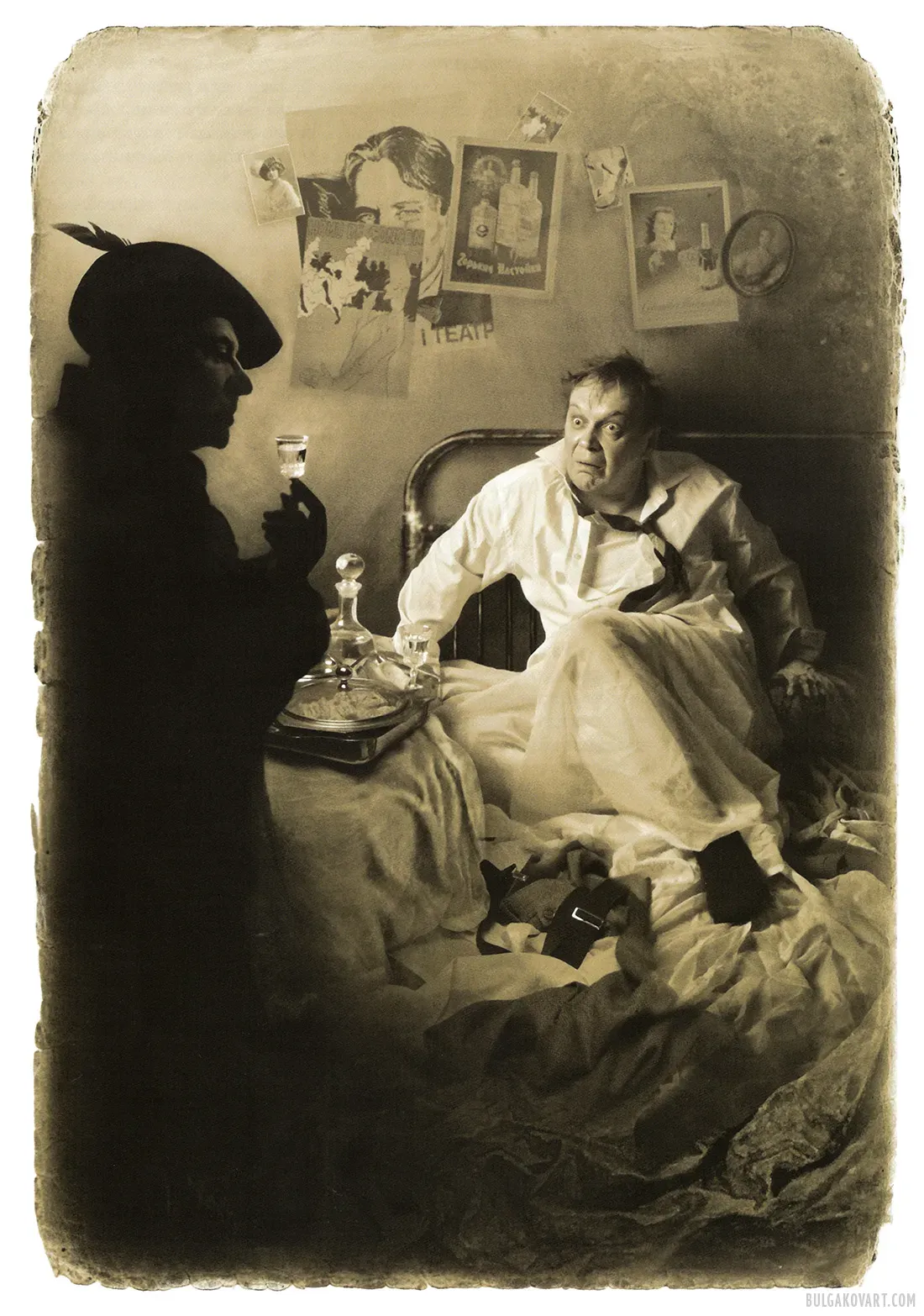

Stepa sat up in bed, bloodshot eyes bulging at the stranger. The silence was broken by that stranger’s low, heavy voice, speaking with a foreign accent:

“Good day, most charming Stepan Bogdanovich!”

Lounging on the jeweler’s pouffe in a rakish pose sprawled a gigantic black cat with a stack of vodka glasses.

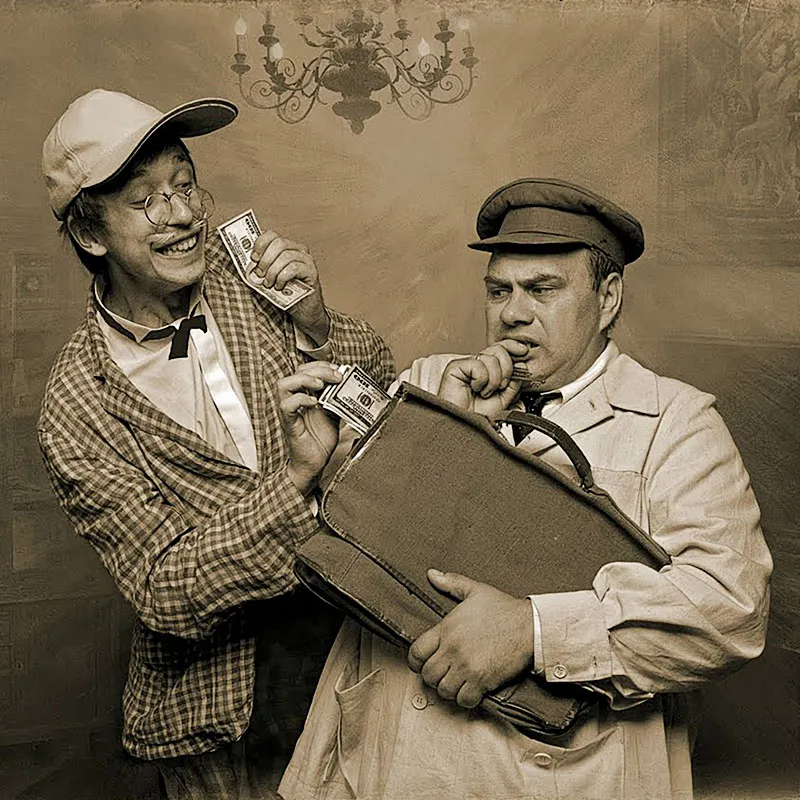

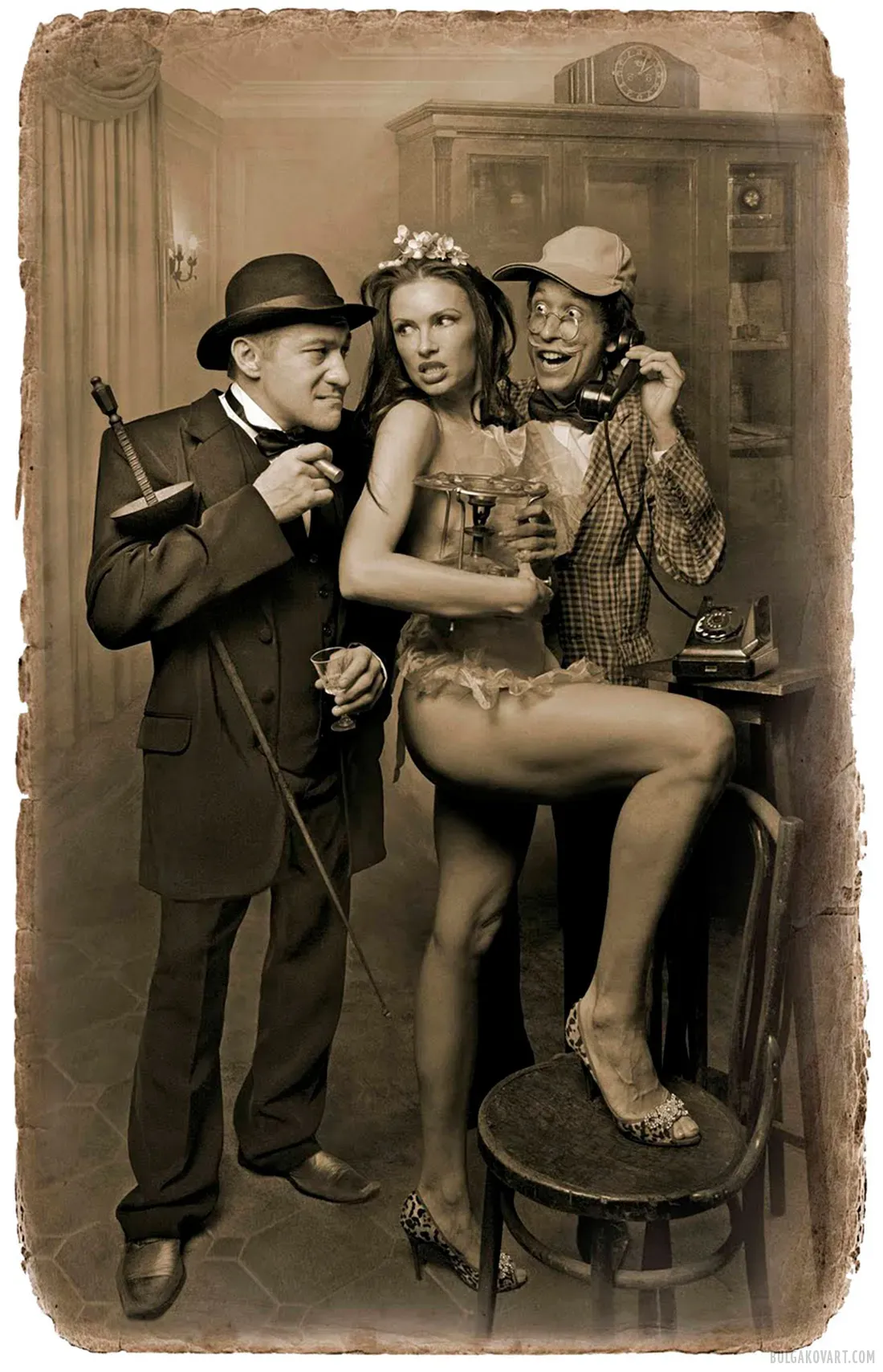

With his left hand the interpreter deftly slipped the ticket to Nikanor Ivanovich, while his right pressed a thick, crackling bundle into the chairman’s other hand. The moment Nikanor Ivanovich glanced at it he blushed crimson and tried to push it away.

“That’s not appropriate…” he mumbled.

“I won’t hear of it,” Koroviev hissed right in his ear.

Then, as the chairman later swore, a miracle occurred: the bundle crawled into his briefcase all by itself.

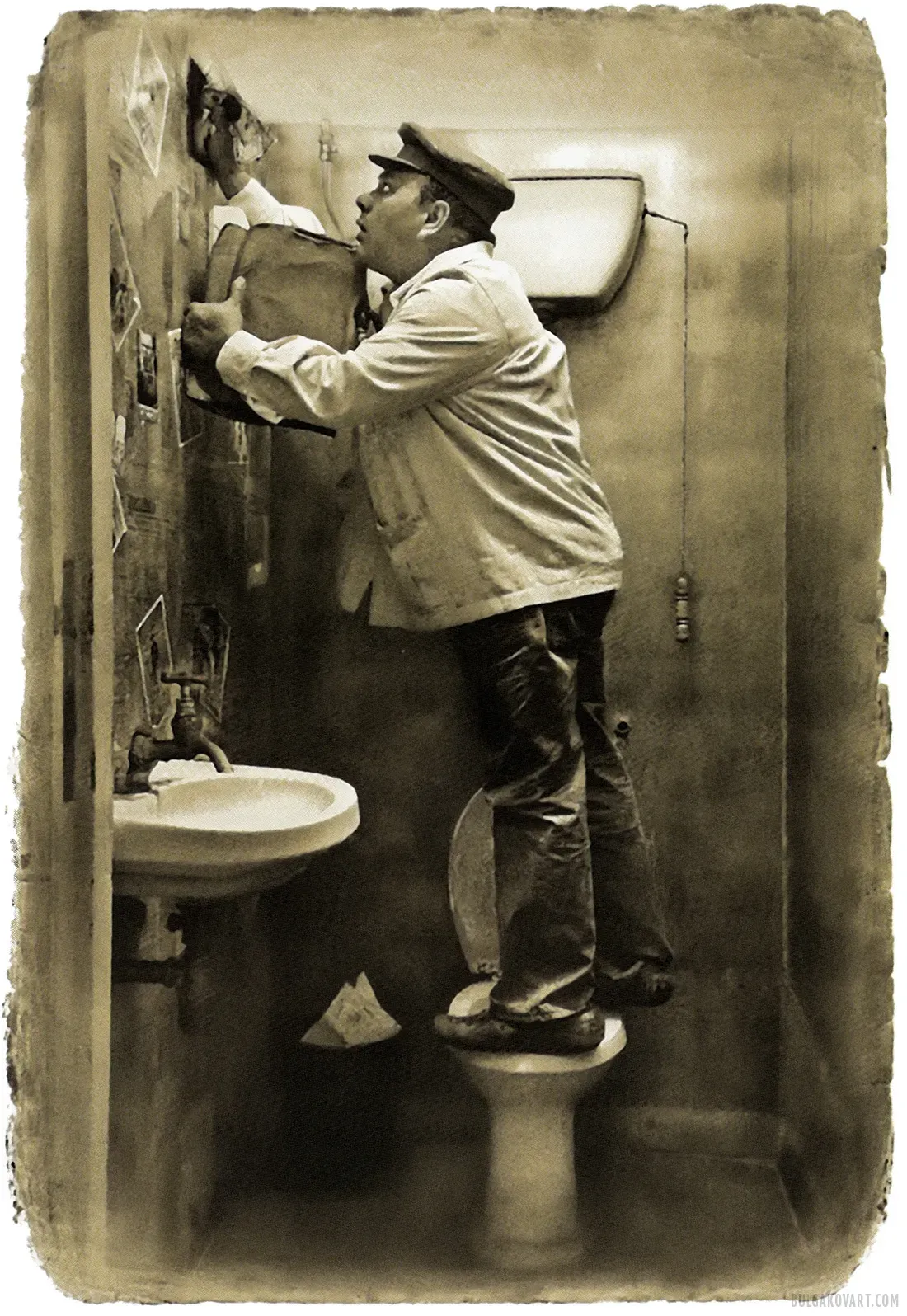

Locking himself in the lavatory, he took out the bundle foisted on him by the interpreter and discovered four hundred rubles. He wrapped it in a scrap of newspaper and stuffed it into the ventilator shaft.

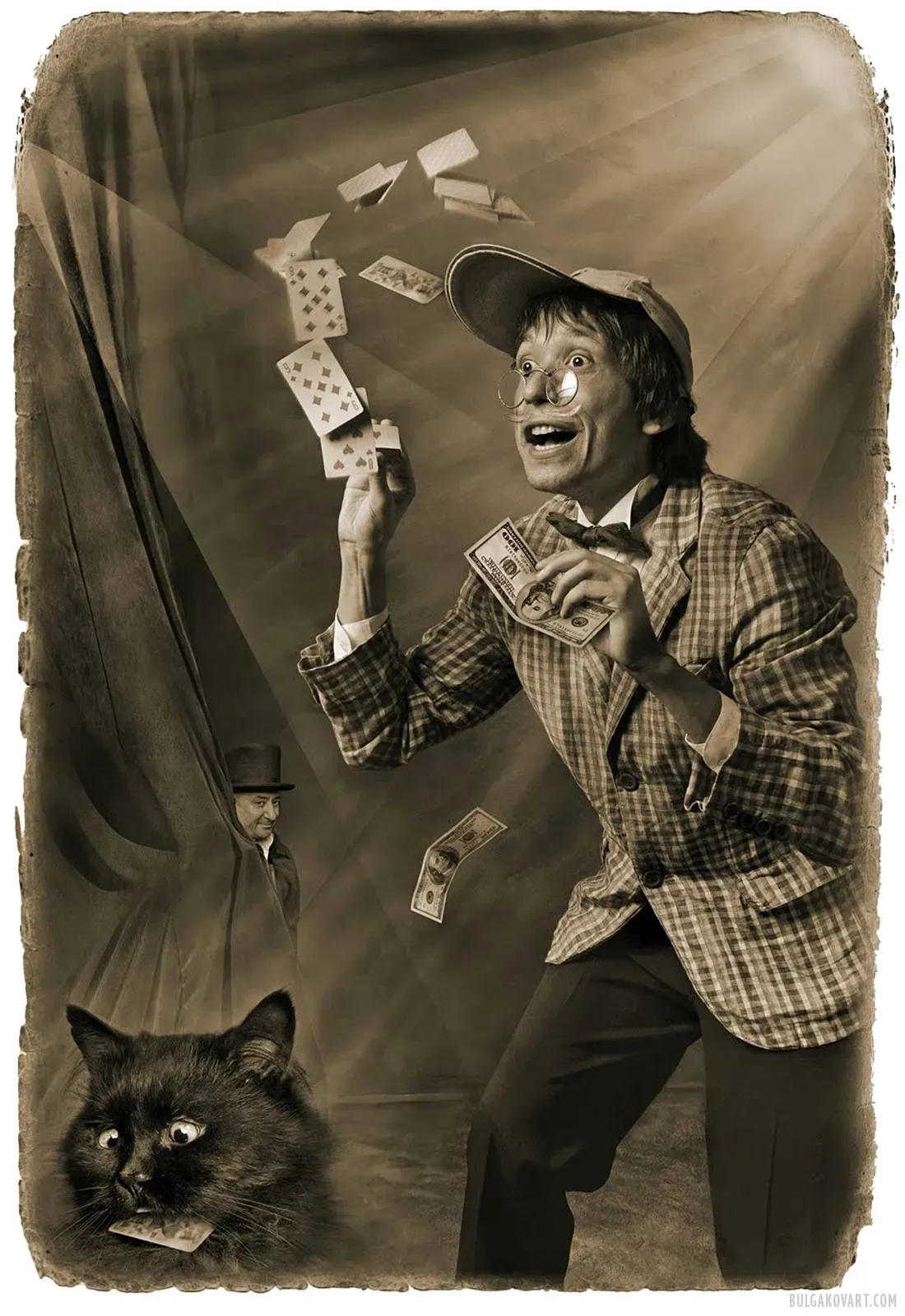

“A chair,” Woland said quietly—at which a chair appeared onstage, from nowhere, and the magician sat down.

Koroviev snapped his fingers, bellowed “One, two, three, four!”—caught a deck of cards out of thin air, riffled it, and sent it flying to the cat.

Respectable citizens adopted the investigators’ view: the deed had been done by a gang of hypnotists and ventriloquists who were superb at their art.

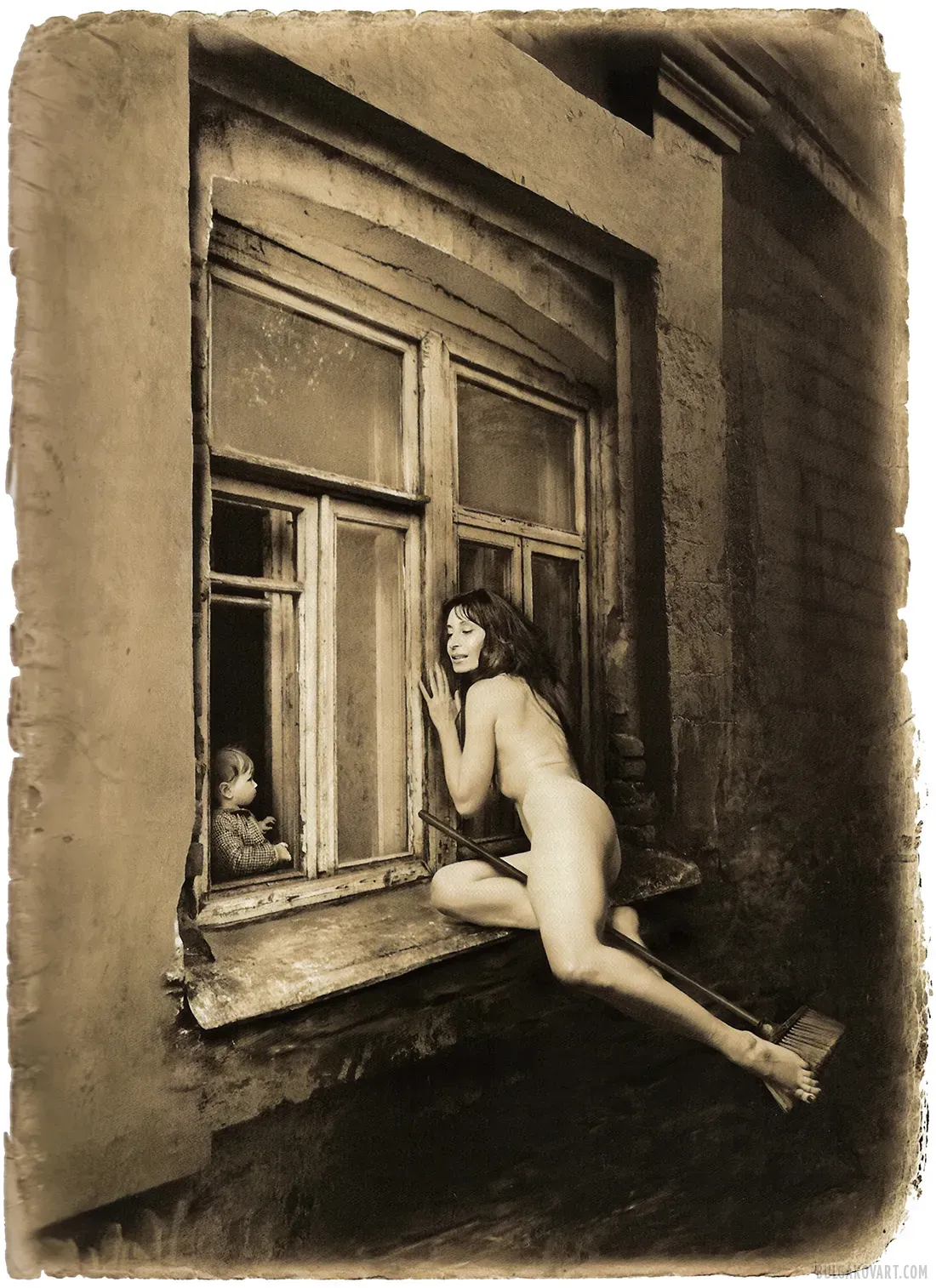

Gliding up to the third floor, Margarita peered into the farthest window, screened by a flimsy dark curtain. A dim lamp burned under a shade. In a little cot with netted sides sat a boy of about four, listening in fright.

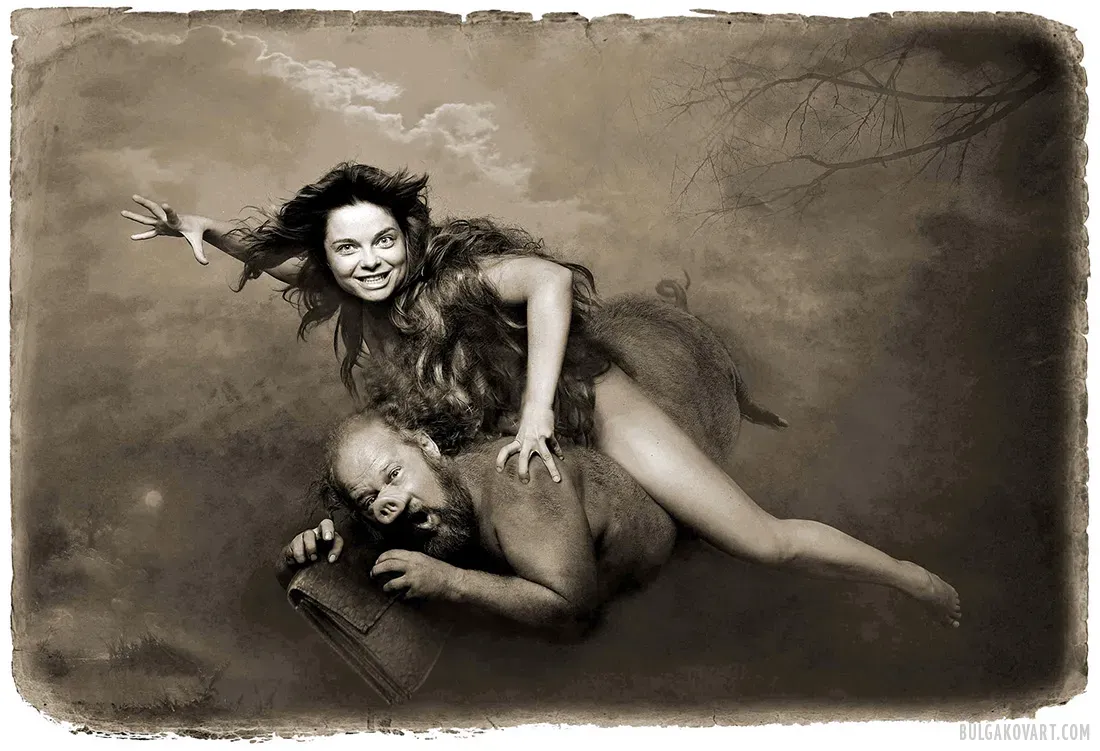

Margarita was overtaken by Natasha—completely naked, hair streaming behind her as she rode a fat hog, front hooves clamped around a briefcase, rear hooves flailing the air.

(Natasha is played by famous Russian singer Natasha Koroleva)

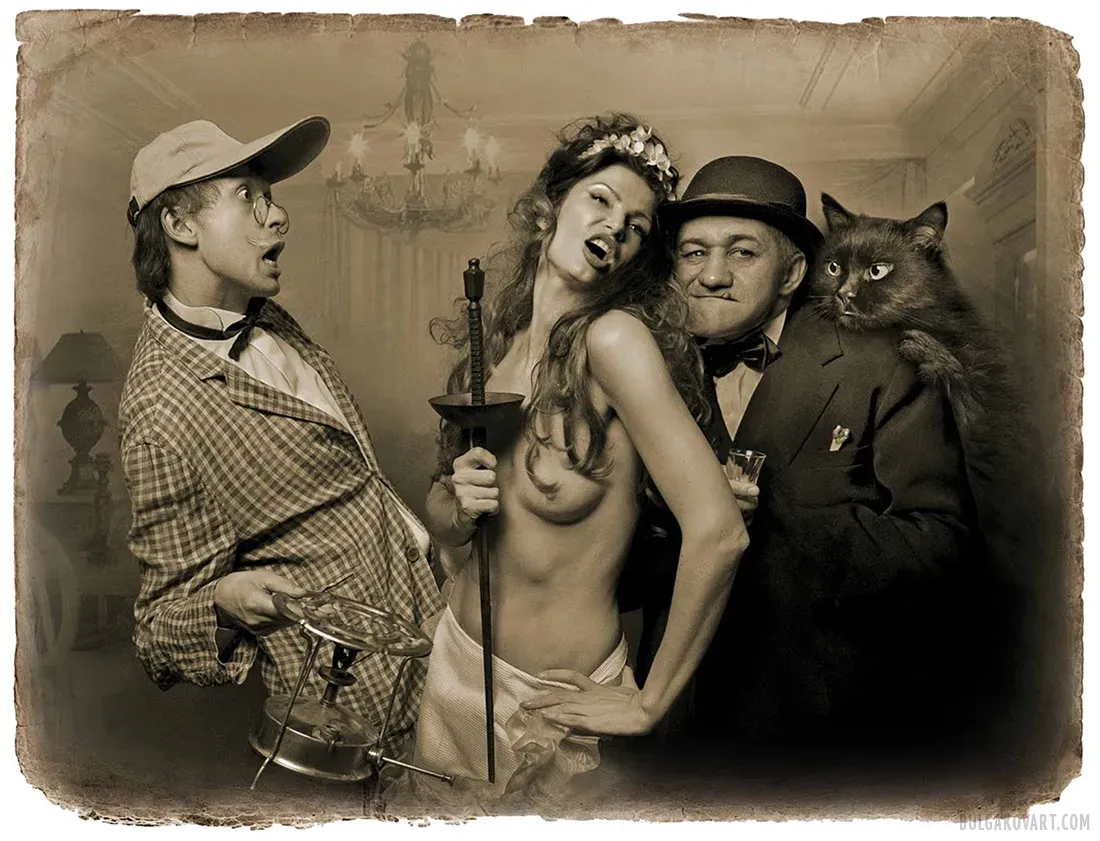

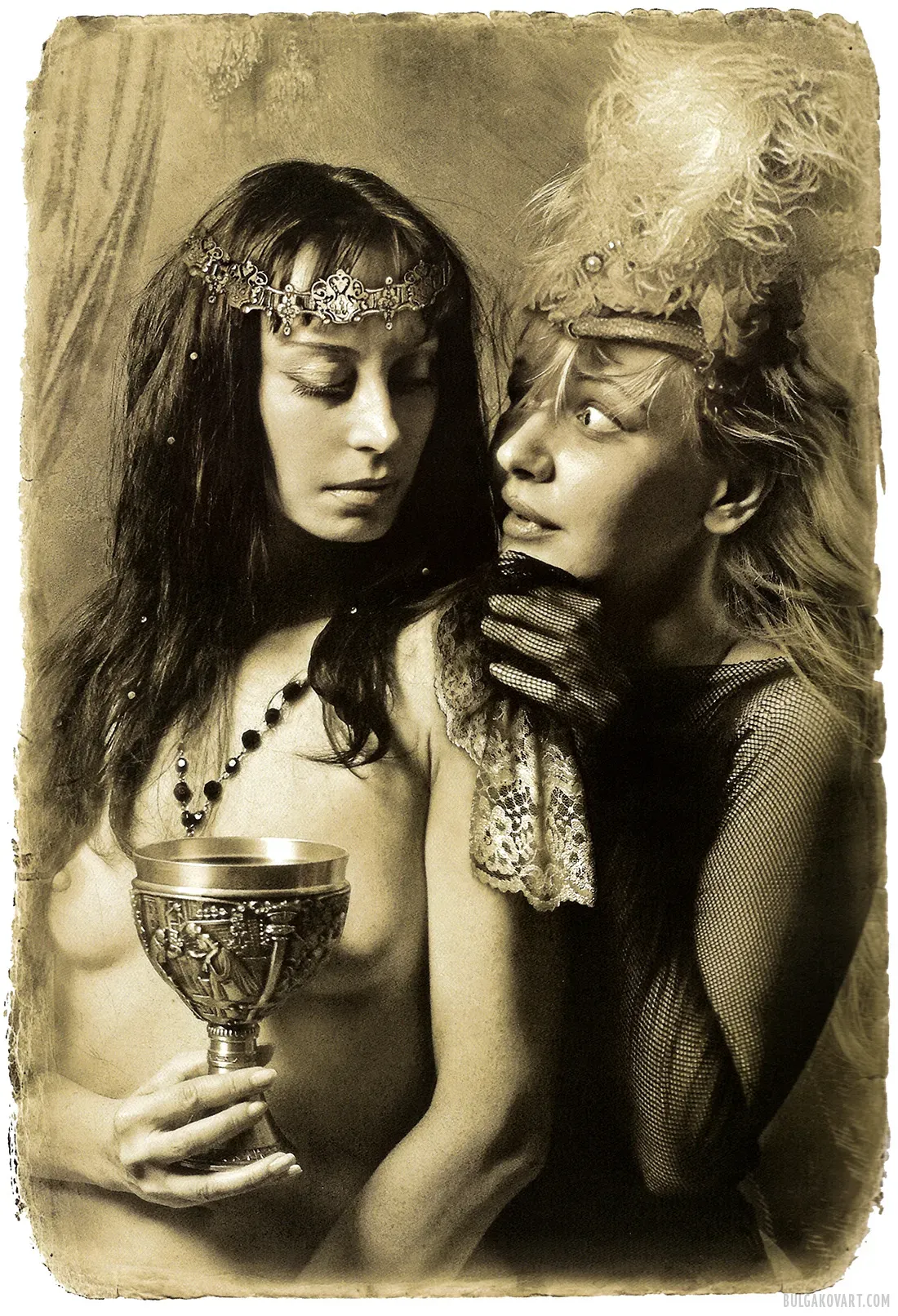

“Permit me, your Majesty, one last piece of advice. Among the guests there will be all sorts—oh, very different sorts—but no favors for anyone, Queen Margot! If someone displeases you… love him all the same, my queen. And another thing: miss no one. A smile if there’s no time for a word, the tiniest tilt of the head—anything but neglect.”

“The queen is delighted!” Koroviev shouted.

“We are delighted!” howled the cat.

“Frida, Frida, Frida! My name is Frida, my Queen!”

Hella and the cat made up; to seal their truce they kissed.

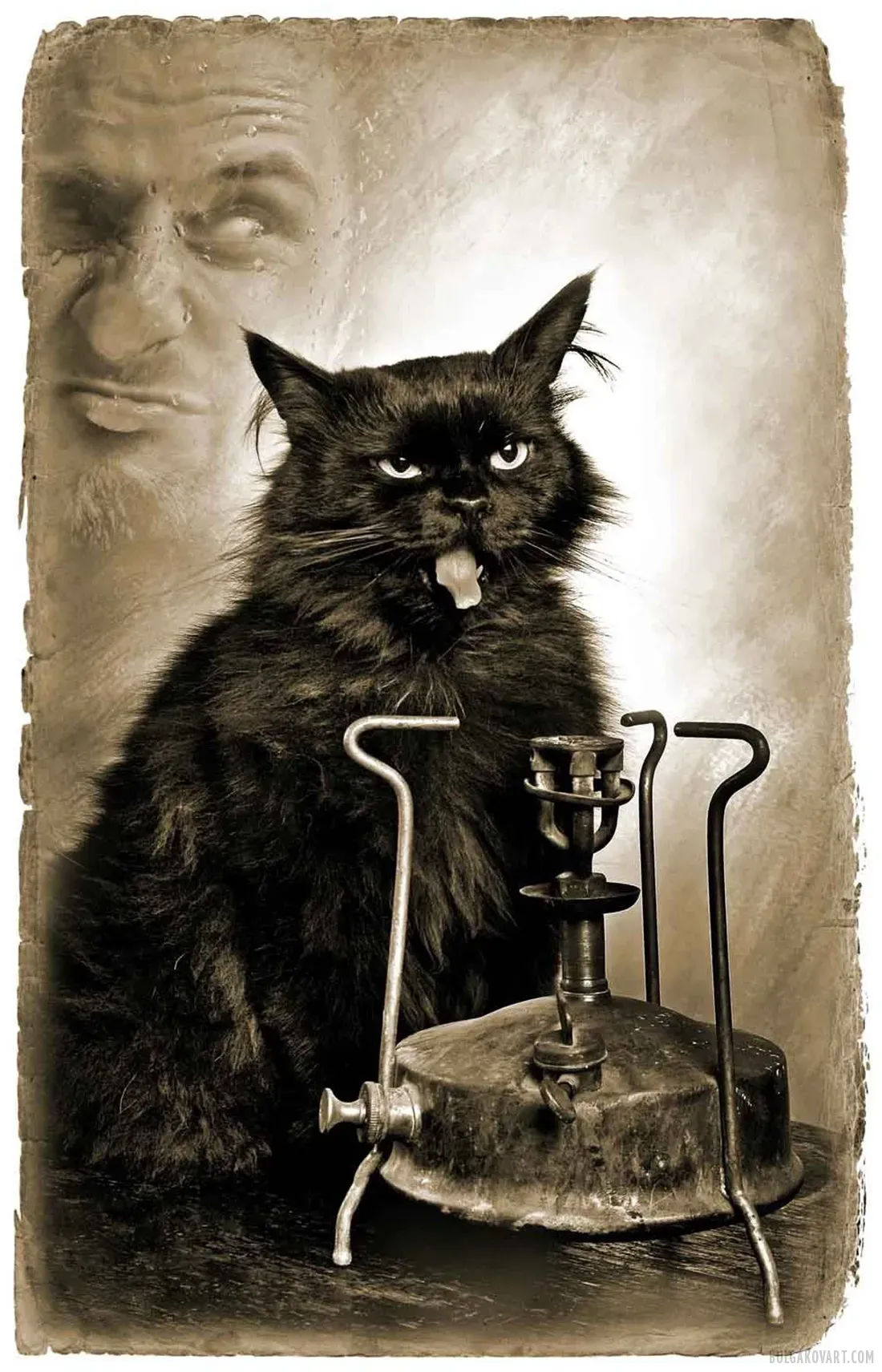

Perched on the mantelpiece sat the enormous black cat, a primus stove in his paws.

“I’m not fooling around, not bothering anyone—just fixing the primus,” he muttered darkly. “And I must remind you that the cat is an ancient and sacred animal.”

Without letting go of the primus, the cat somehow vaulted into the air and landed on the chandelier.

“I challenge you to a duel!” he roared while swinging overhead, a Browning suddenly in his paw.

Behemoth left the confectionery temptations, plunged a paw into a barrel marked “Selected Kerch Herring,” pulled out two herrings, swallowed them, and spat out the tails.

One of Ha‑Notsri’s secret friends, outraged by the money‑changer’s monstrous betrayal, conspires with accomplices to kill him that very night and to throw the blood money back to the high priest with a note: “I return the cursed silver!”

At sunset, high above the city on the stone terrace of one of Moscow’s loveliest buildings—raised some one‑hundred‑and‑fifty years ago—stood two figures: Woland and Azazello. From the street they were hidden by a balustrade of plaster urns and flowers, but the city lay open before them to the very horizon.

Night thickened beside them, snatching at the flyers’ cloaks, tearing them away and exposing deceit. When Margarita, buffeted by a cool wind, opened her eyes, she saw every disguise fall away from the riders bound for their goal. And when a crimson, swollen moon rose over the forest edge, all deception vanished: the witches’ flimsy garments slipped into bogs, drowned in mist.

For nearly two thousand years he has sat on that ledge and slept, but when the full moon comes, as you see, insomnia torments him. It torments not only him but his faithful watchdog. If cowardice is indeed the worst sin, perhaps the dog is innocent—for the brave beast feared only thunder. Well, one who loves must share the fate of the one he loves.