Enrico Riposati painted these watercolors in 2006–2007. But who Enrico Riposati himself is remains a complete mystery. I was unable to find any useful information about him, let alone a photograph. He seems to have a blog, but no details about the author can be gleaned from there either. If you happen to have any information about this mysterious artist, please don't hesitate to share it with me. But for now, let's take a look at his rather expressive works.

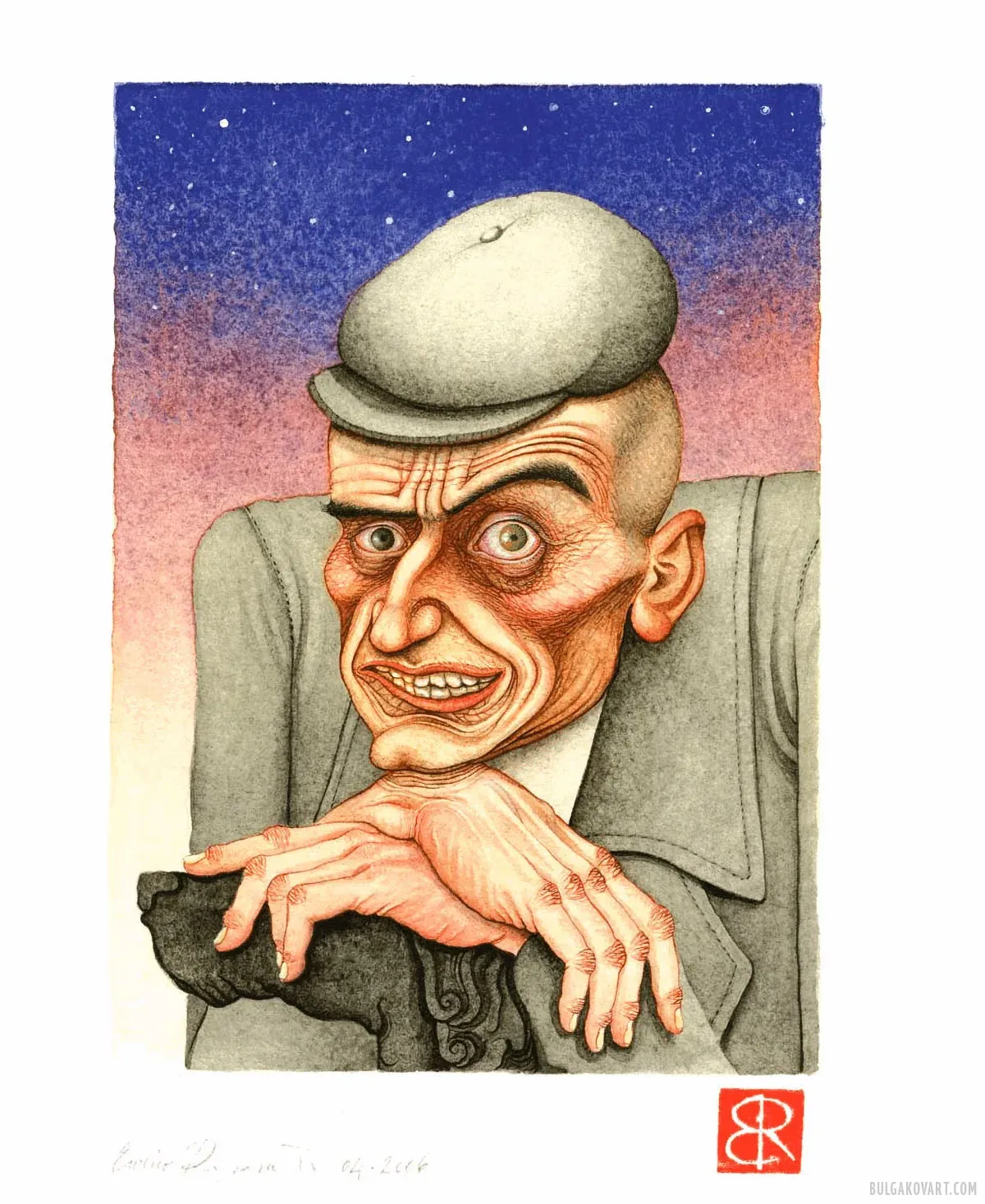

He smiled condescendingly at something, squinted, placed his hands on the knob, and his chin on his hands.

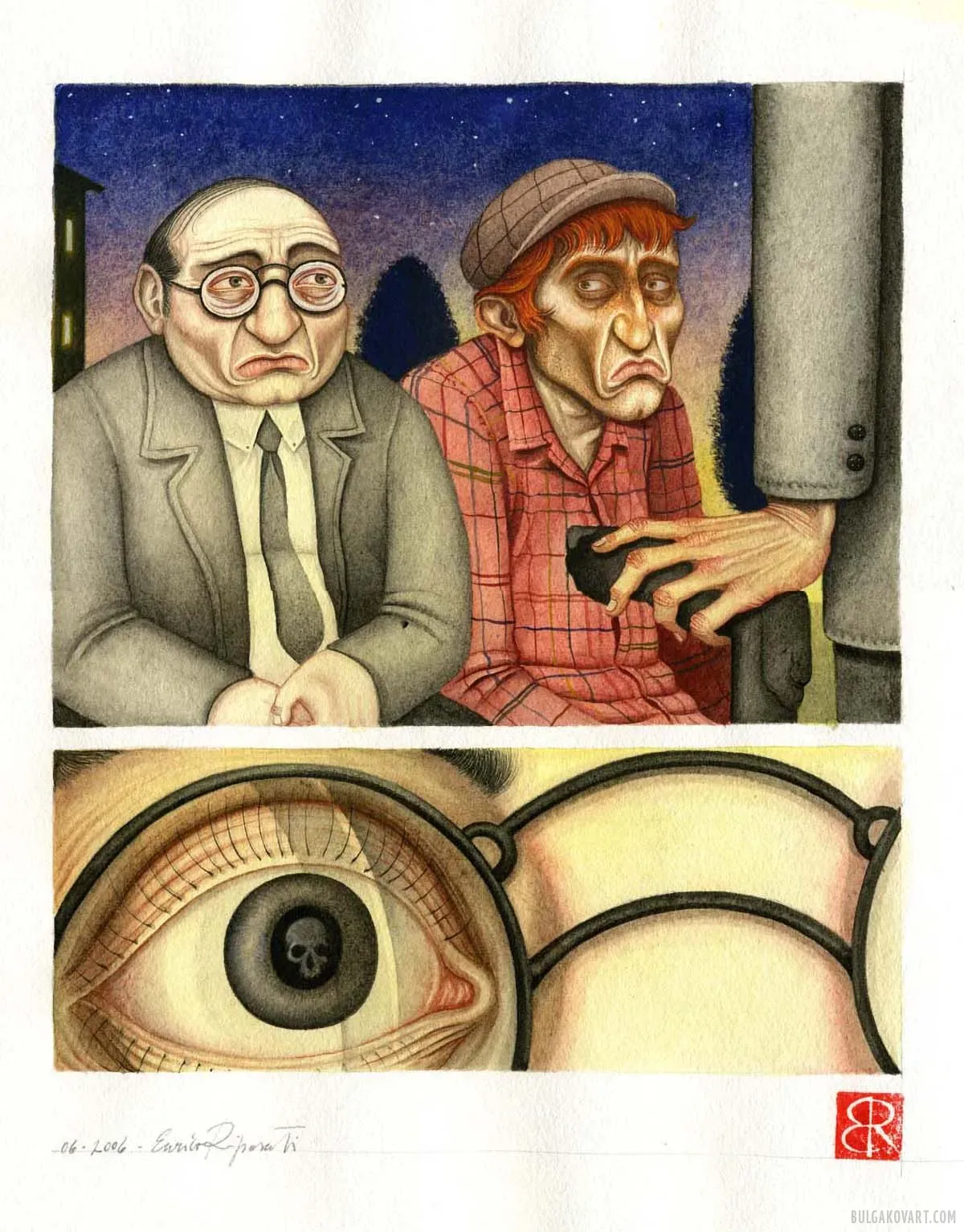

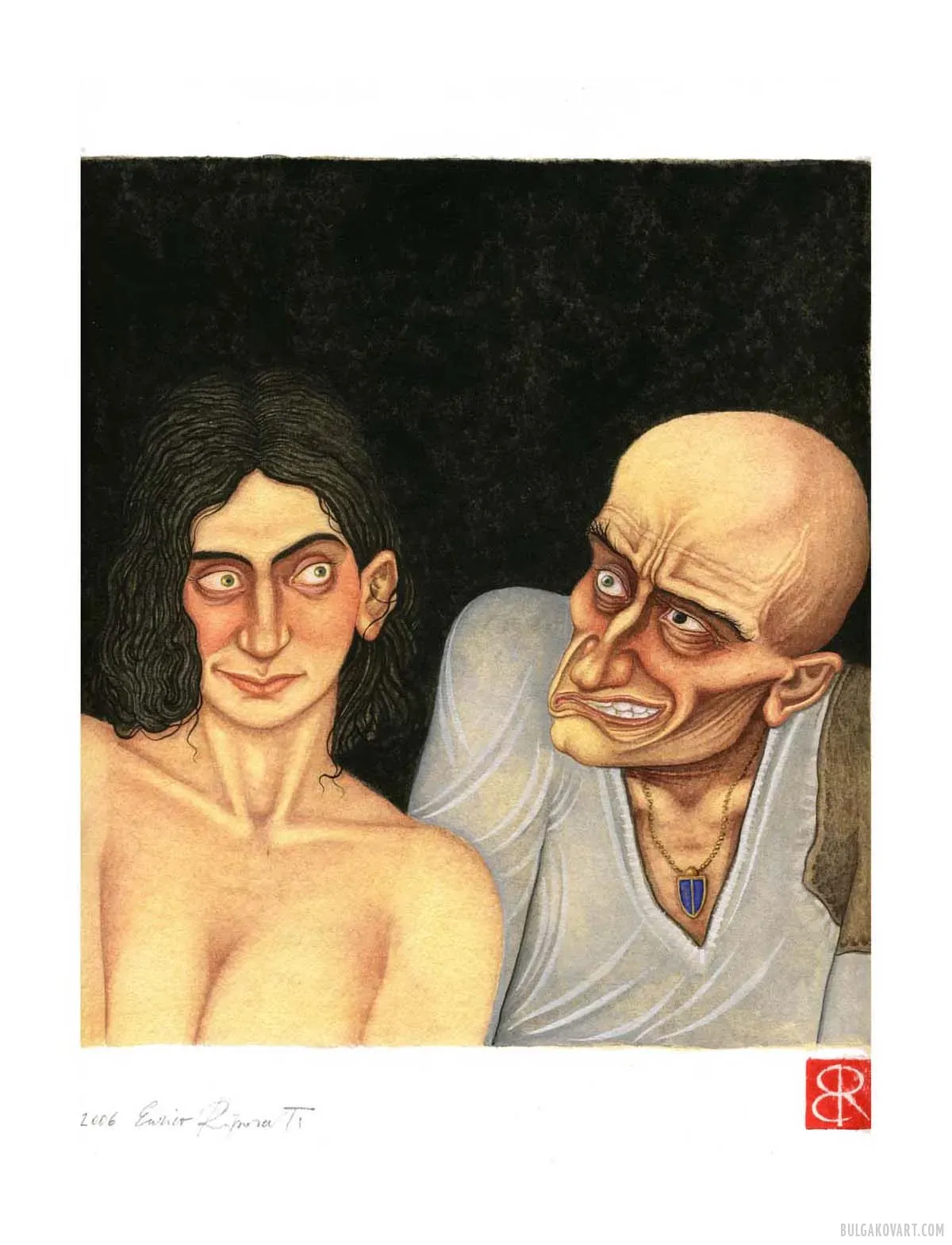

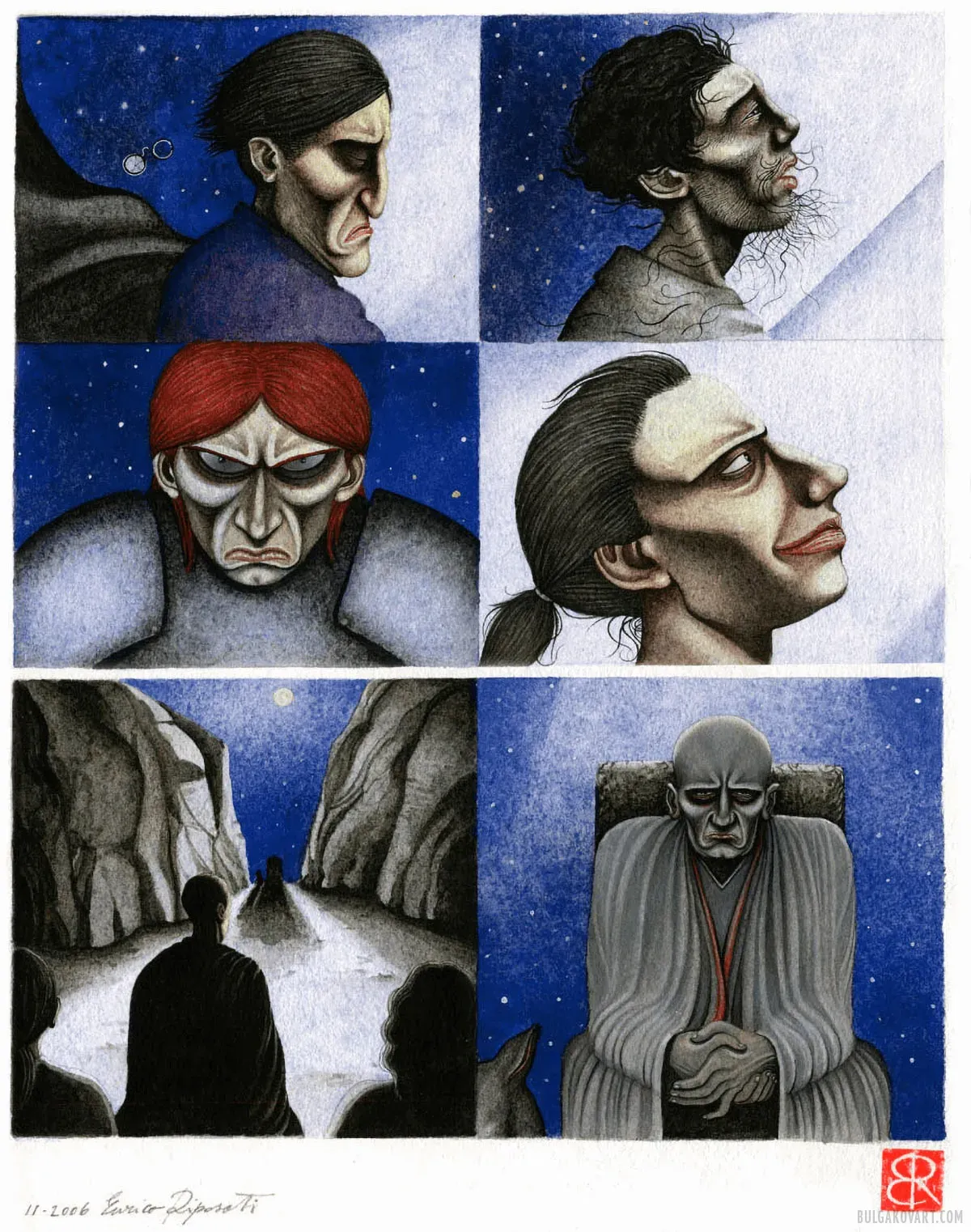

His companions finally thought to look him in the eyes and were convinced that the left one, the green one, was completely insane, while the right one was empty, black, and dead.

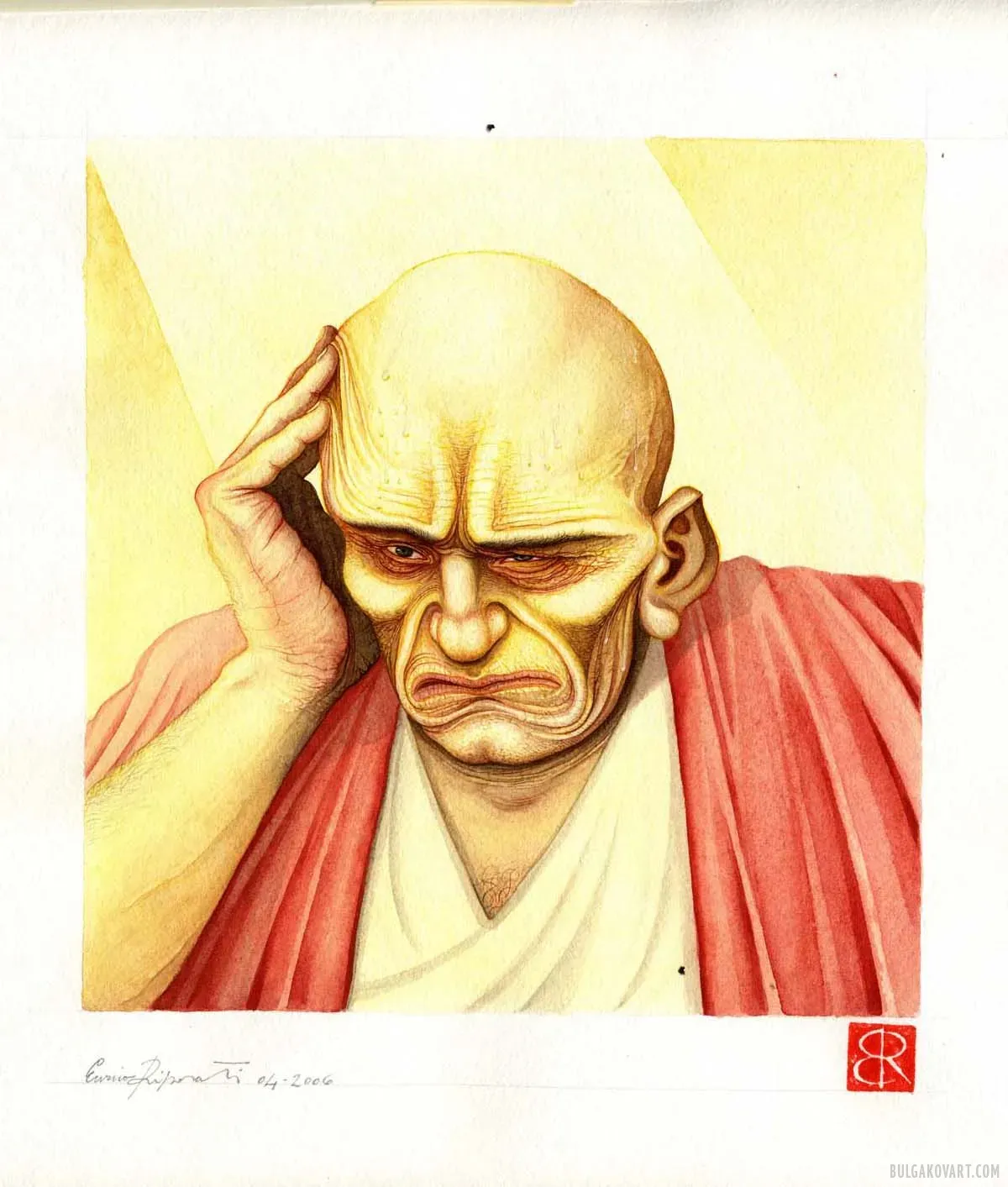

“Yes, there's no doubt! It's her, her again, the unconquerable, terrible illness hemicrania, which makes half of the head ache. There are no remedies for it, no salvation. I'll try not to move my head.”

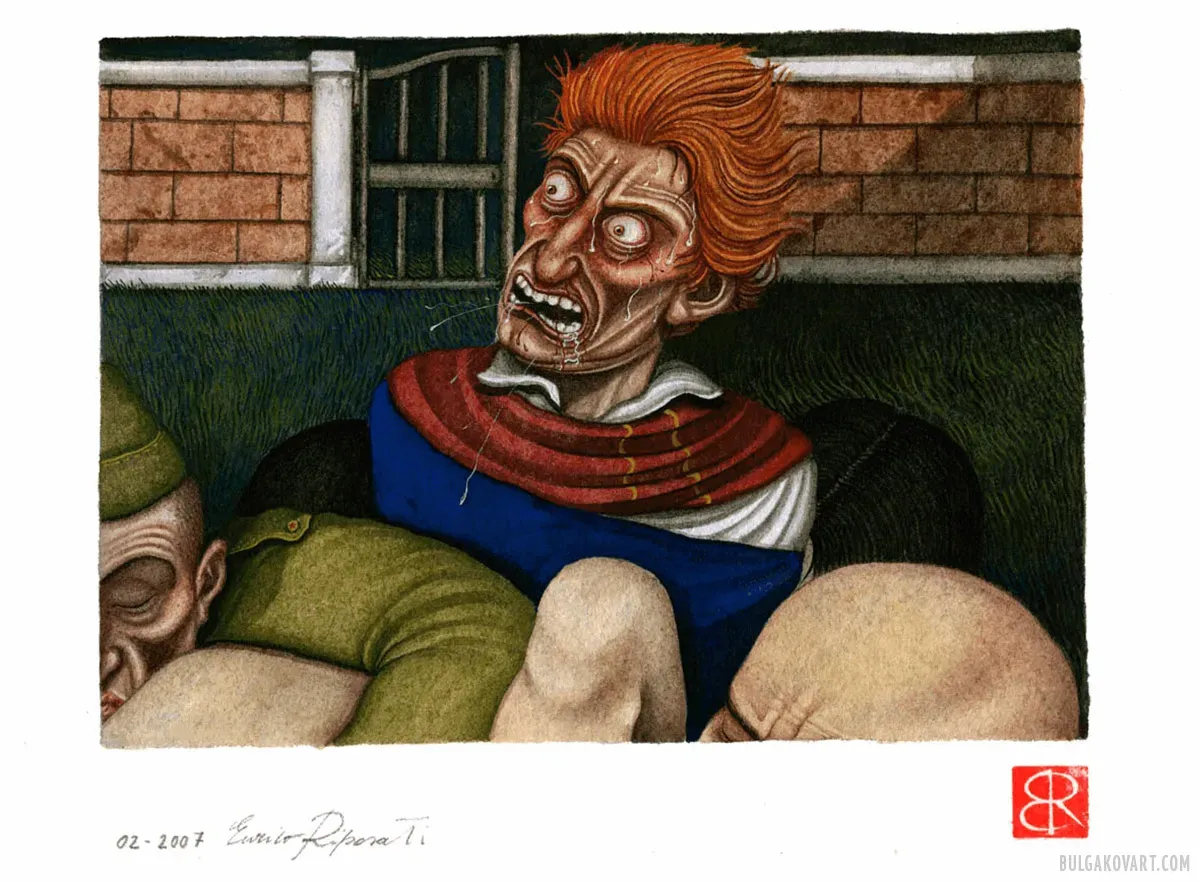

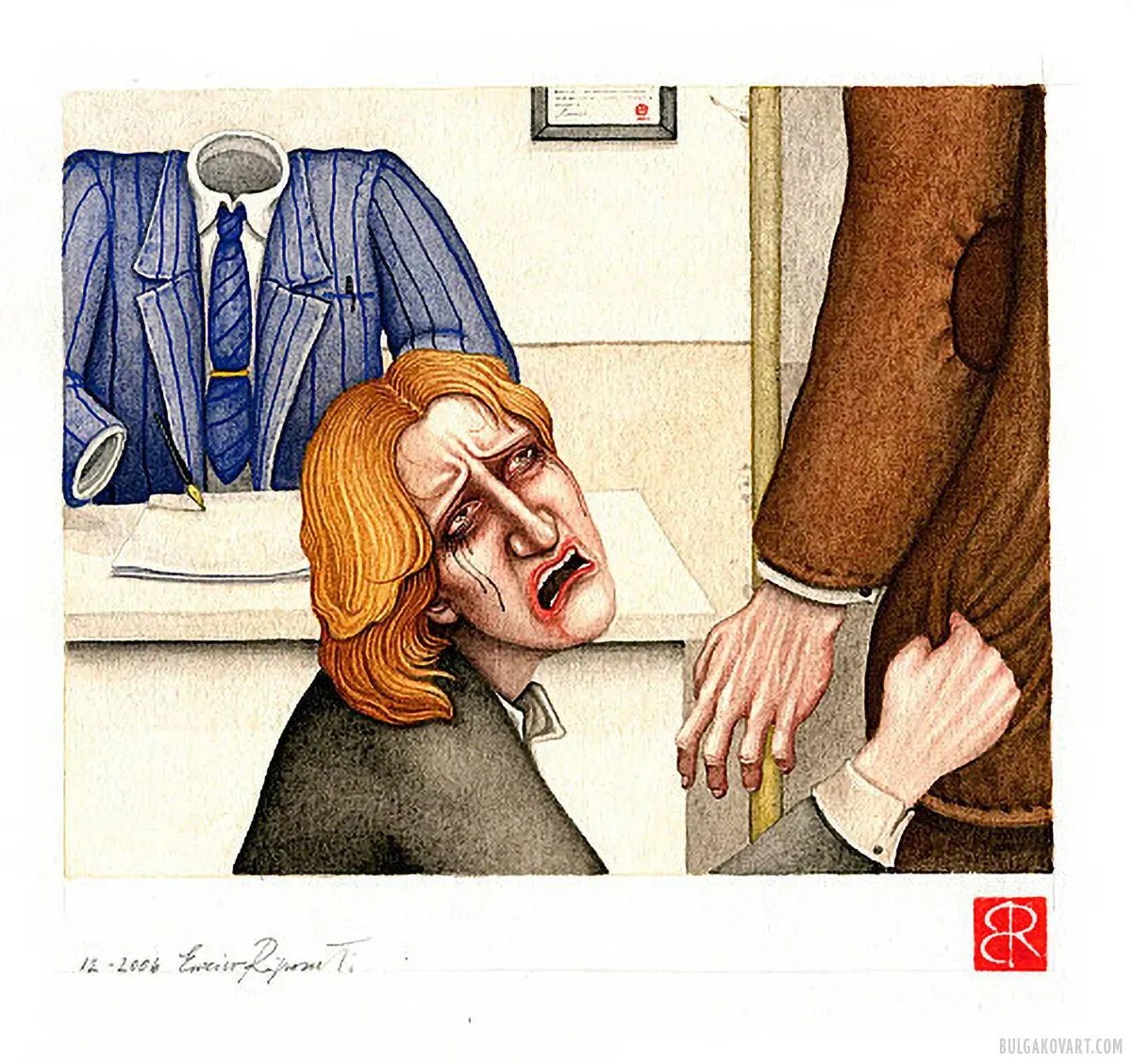

Ivan struggled in the hands of the orderlies. He was wheezing, trying to bite, and shouting, “Let go! I said, let go!”

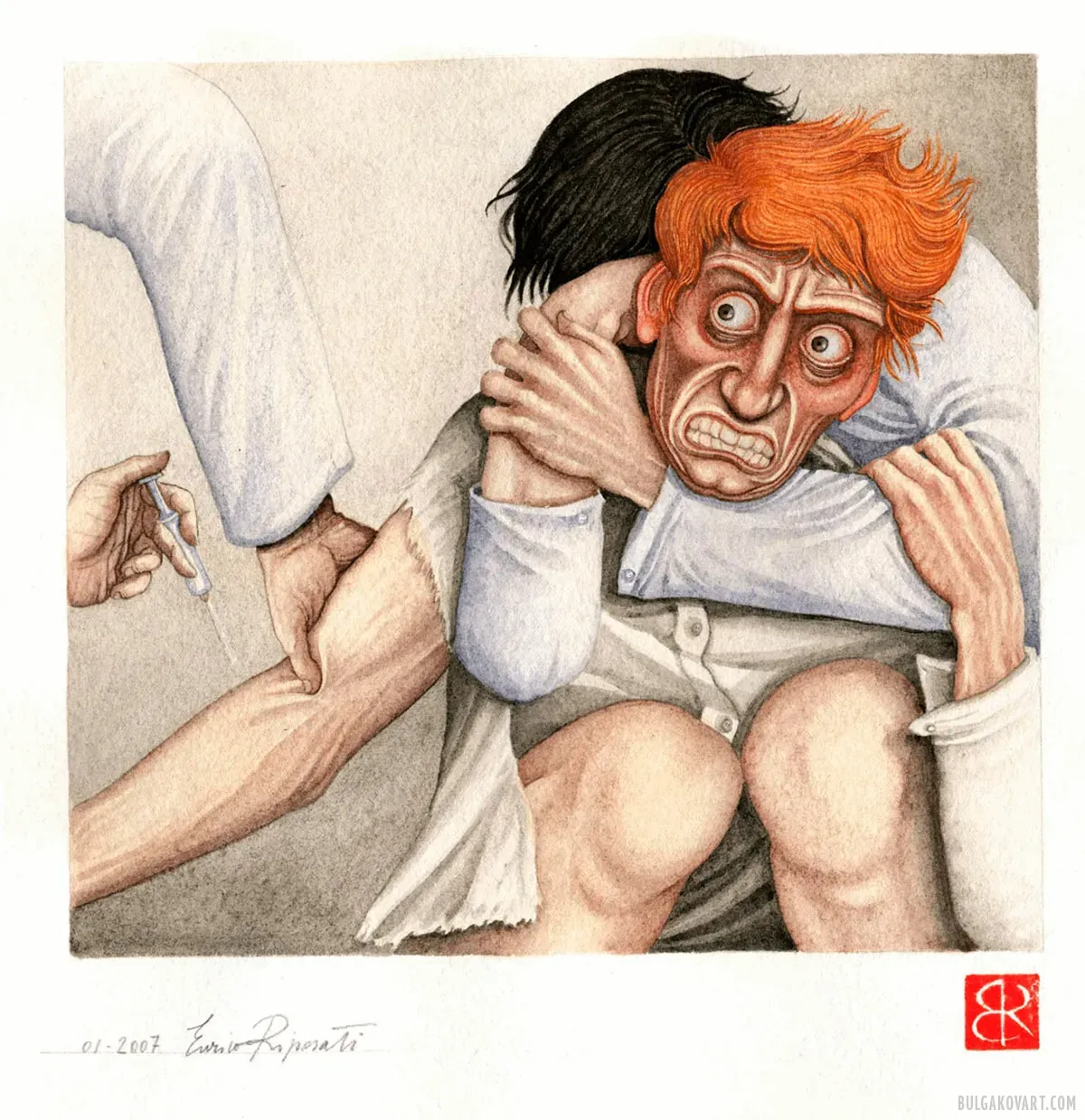

A syringe gleamed in the doctor's hands, the woman with a single motion ripped open the worn sleeve of the shirt and clung to the arm with un-womanly strength. Ivan weakened in the hands of four people, and the nimble doctor took advantage of this moment and injected the needle into Ivan's arm.

“I need to talk to you,” Ivan Nikolaevich said meaningfully.

“That's what I came for,” Stravinsky replied.

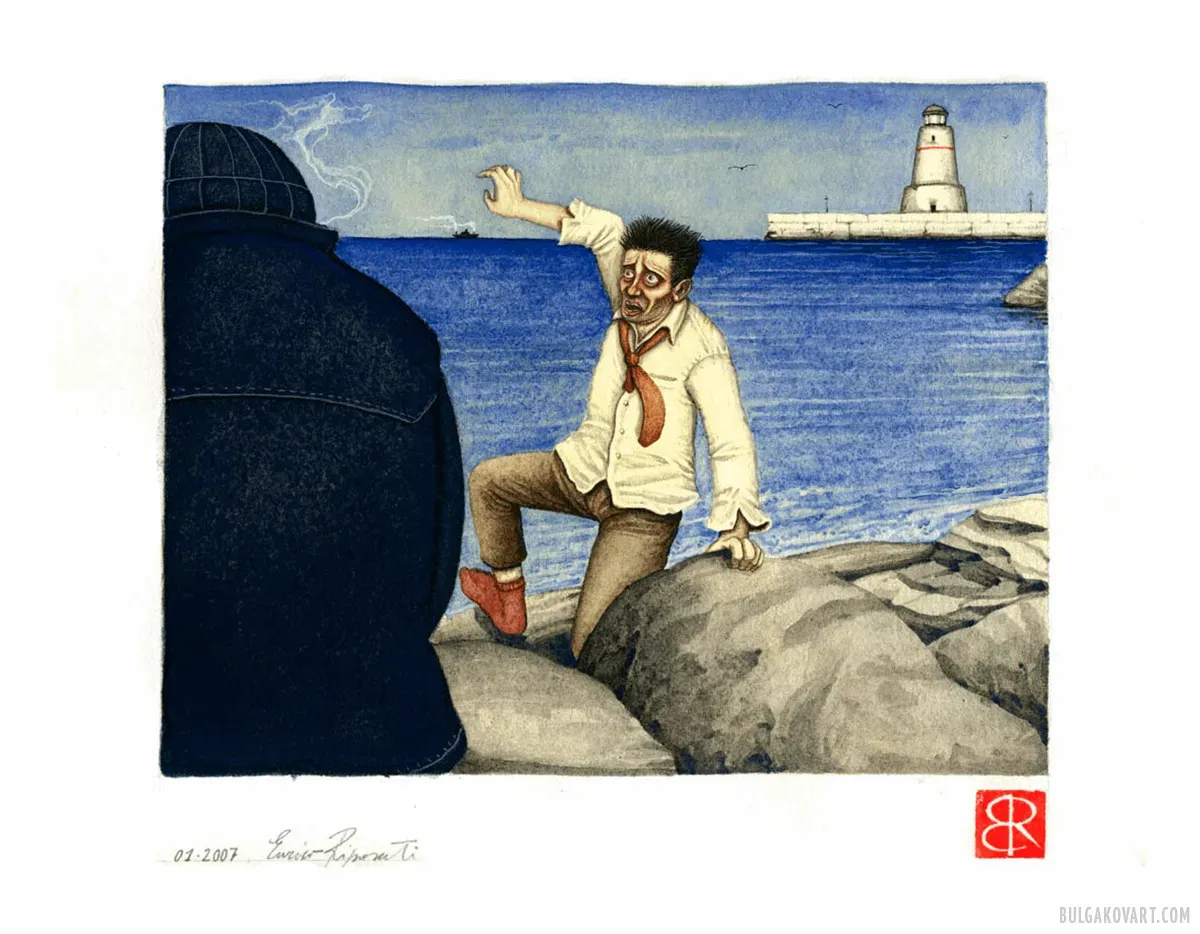

When he finally opened his eyes properly, he saw that the sea was roaring, and even more than that, a wave was swaying at his very feet, and that, in short, he was sitting at the very end of a pier, and that below him was the blue, sparkling sea, and behind him was a beautiful city on the mountains. Not knowing what to do in such cases, Styopa rose to his trembling feet and walked along the pier towards the shore.

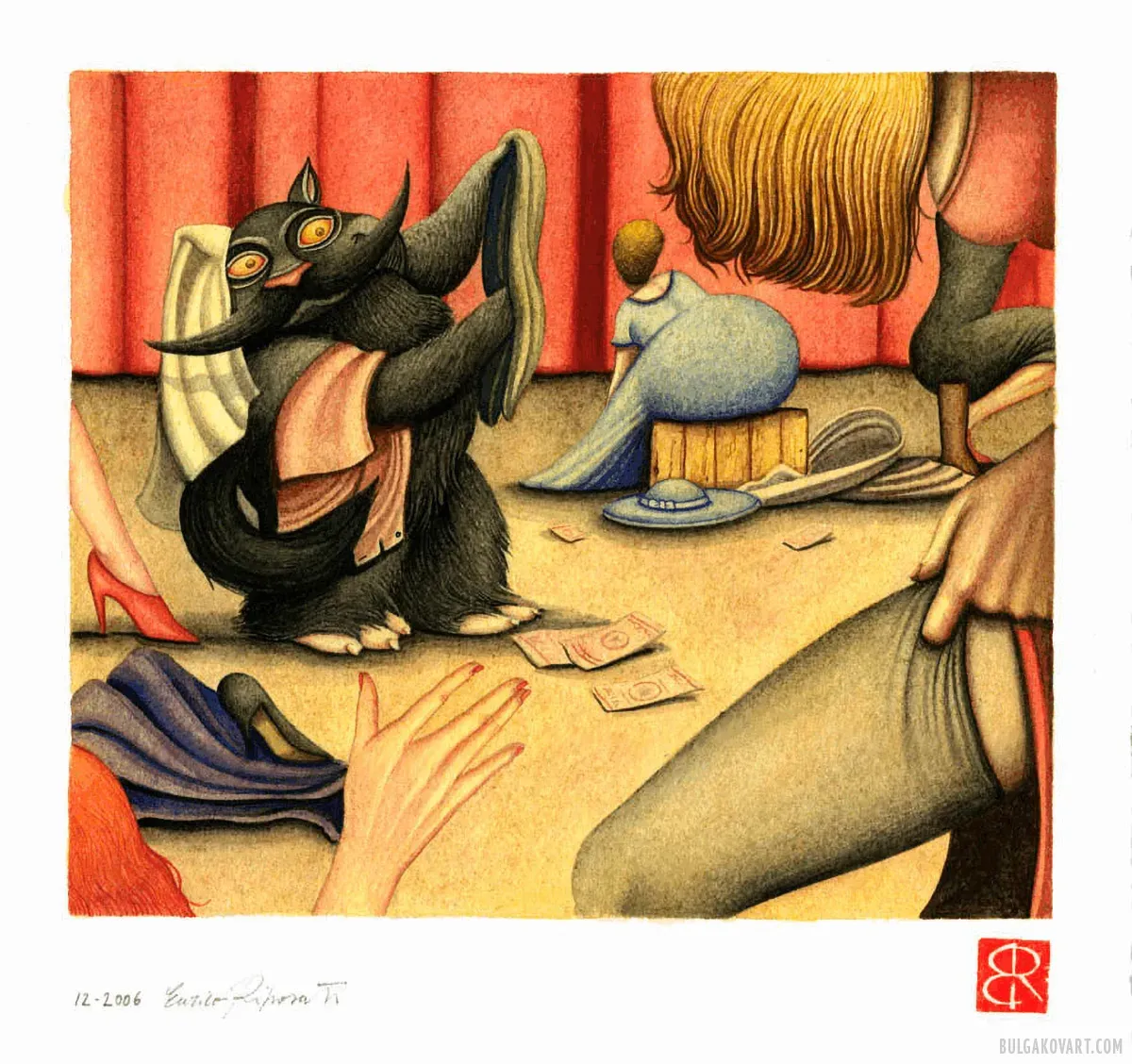

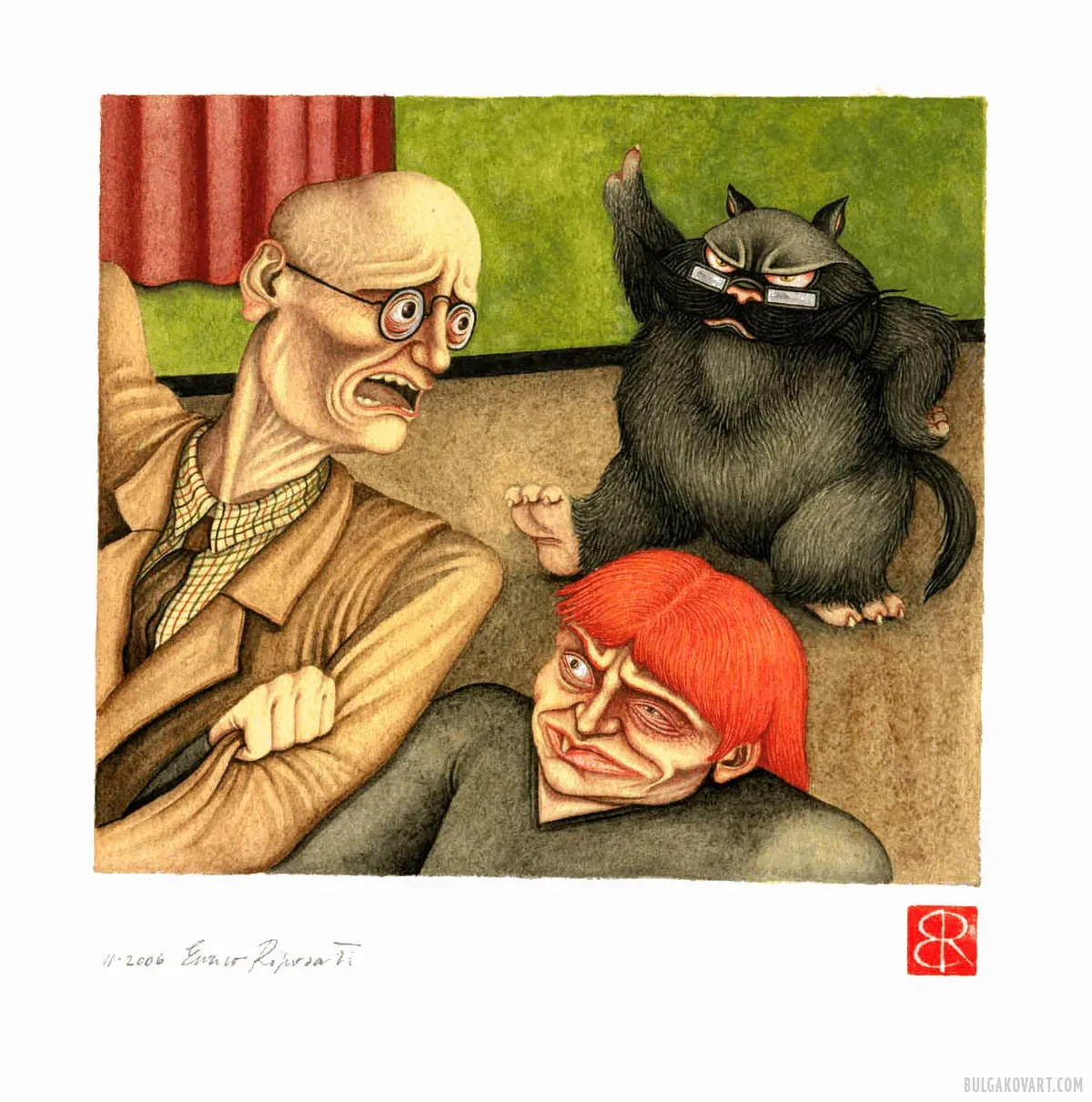

And this is where the dam broke completely, and women came onto the stage from all sides. On stools with gilded legs sat a whole row of ladies, energetically stomping their newly shod feet into the carpet. The cat, exhausted under the piles of handbags and shoes, dragged himself from the display case to the stools and back again.

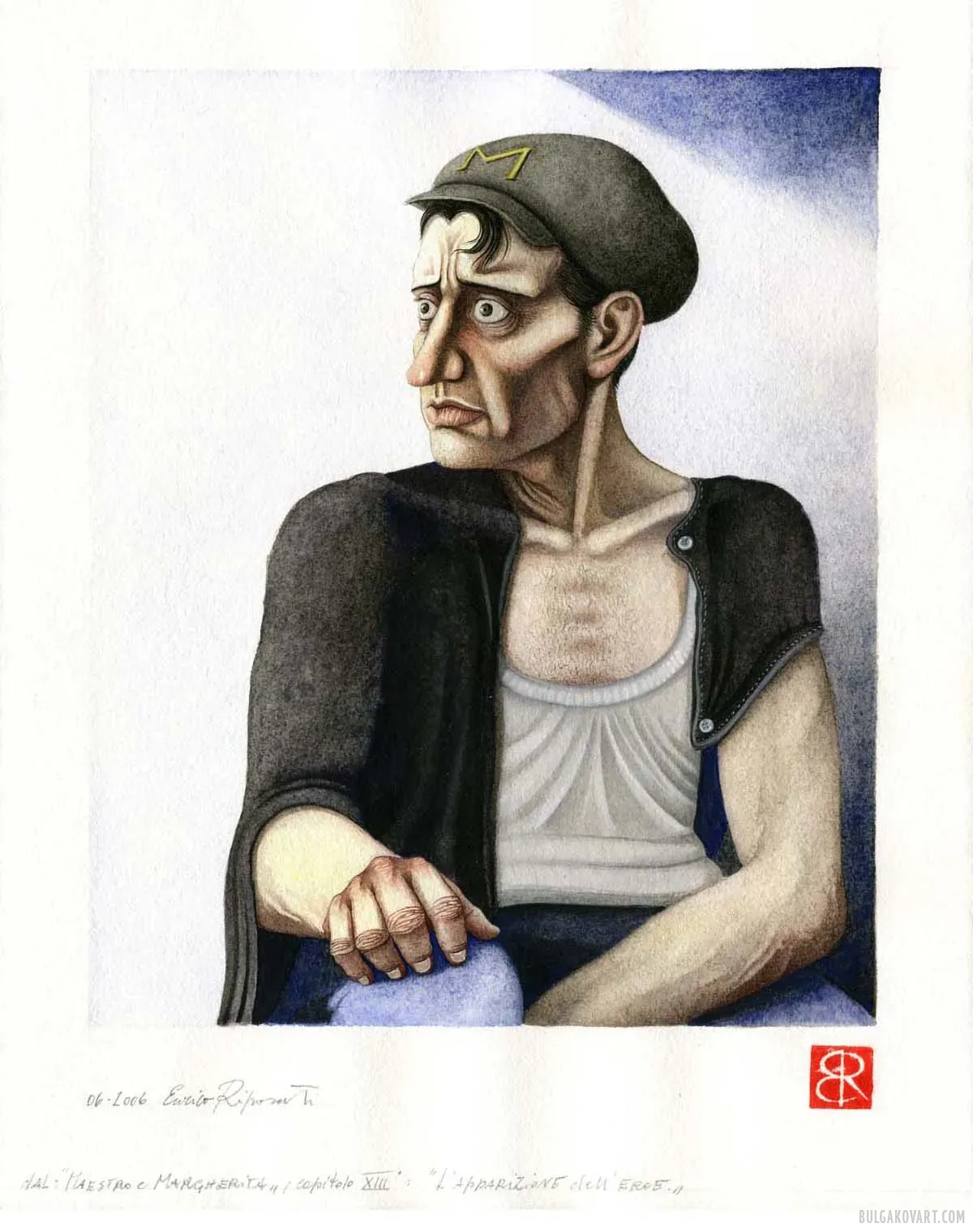

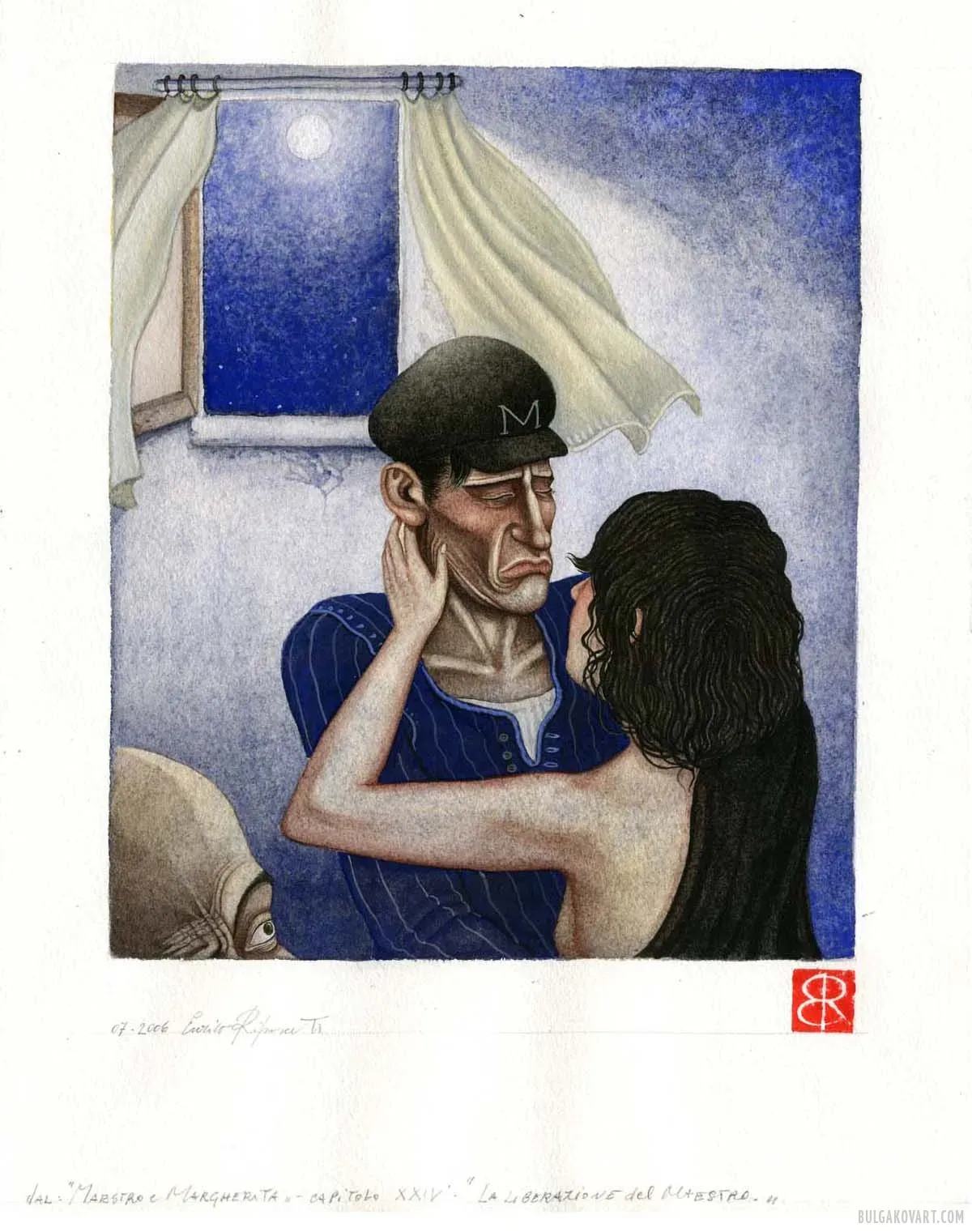

“I am the Master,” he said, becoming stern and taking from his dressing gown pocket a completely greasy black cap with the letter M embroidered on it in yellow silk.

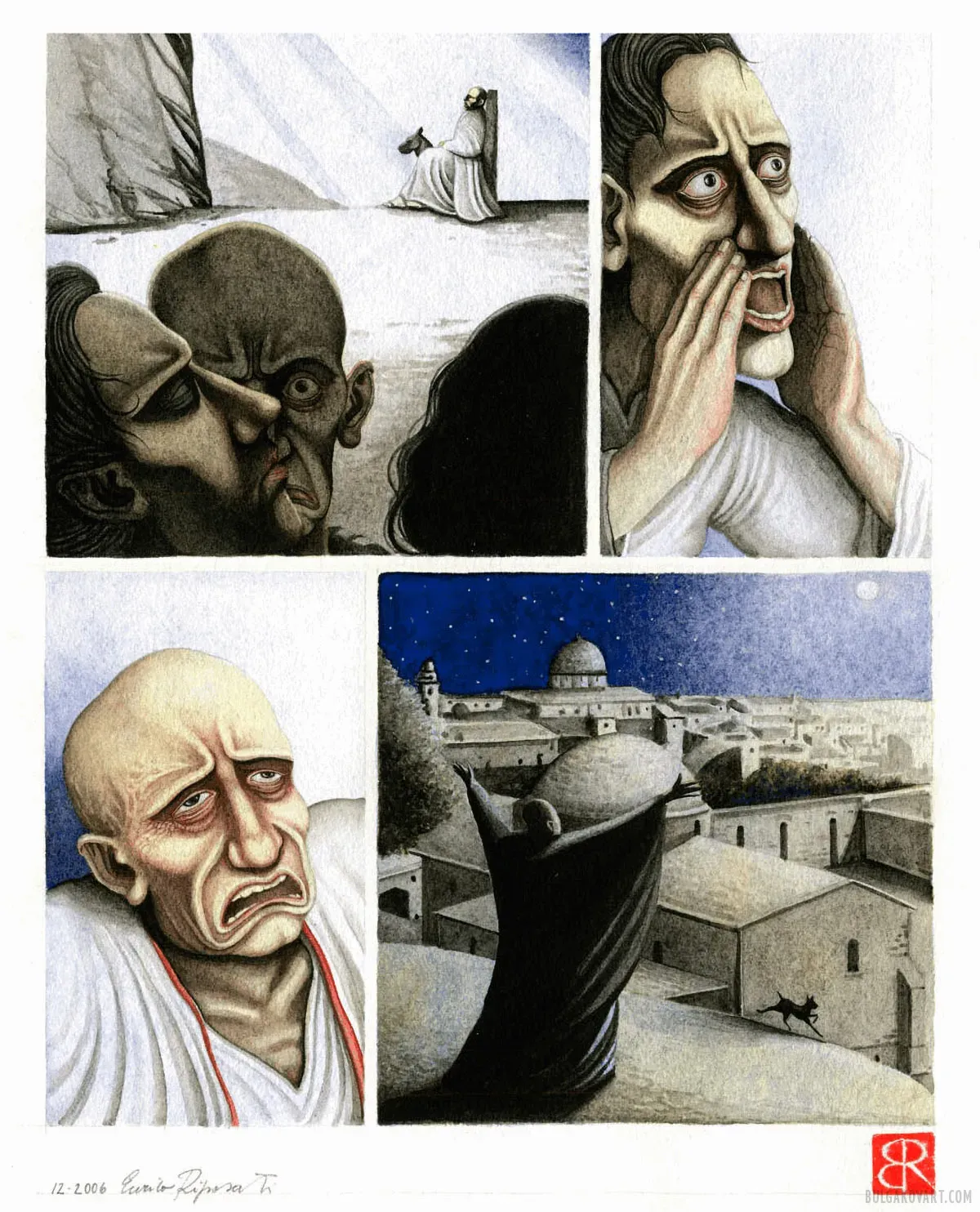

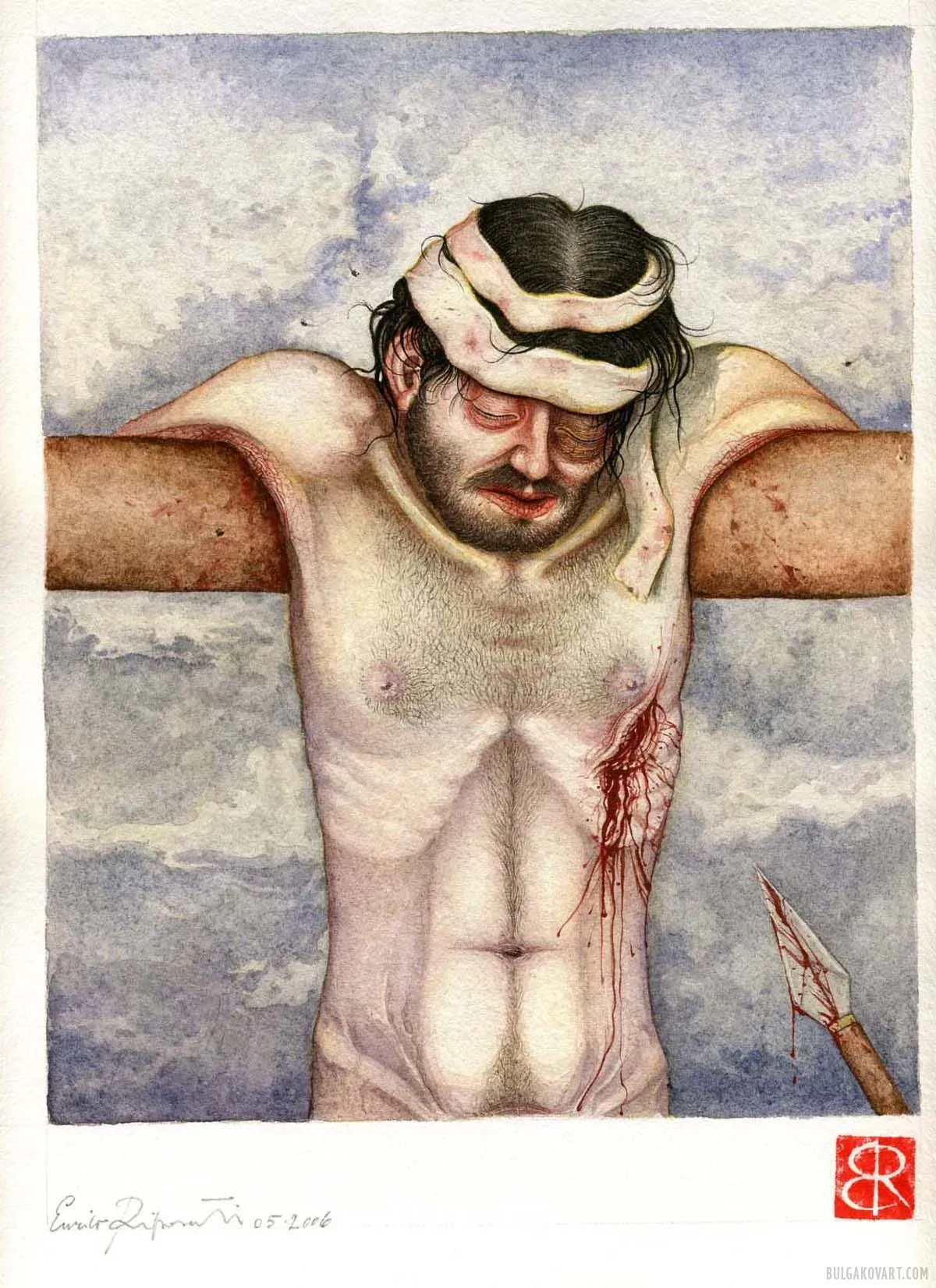

The executioner took the sponge off the spear. “Praise the magnanimous hegemon!” he whispered solemnly and quietly pricked Yeshua in the heart.

Matthew Levi was hiding in a cave on the northern slope of Bald Skull, waiting for darkness. The naked body of Yeshua Ha-Notsri was with him. When the guards entered the cave with a torch, Levi fell into despair and malice. He shouted that he had committed no crime and that every man, according to the law, has the right to bury an executed criminal if he so desires. Levi Matvey said that he did not want to part with this body.

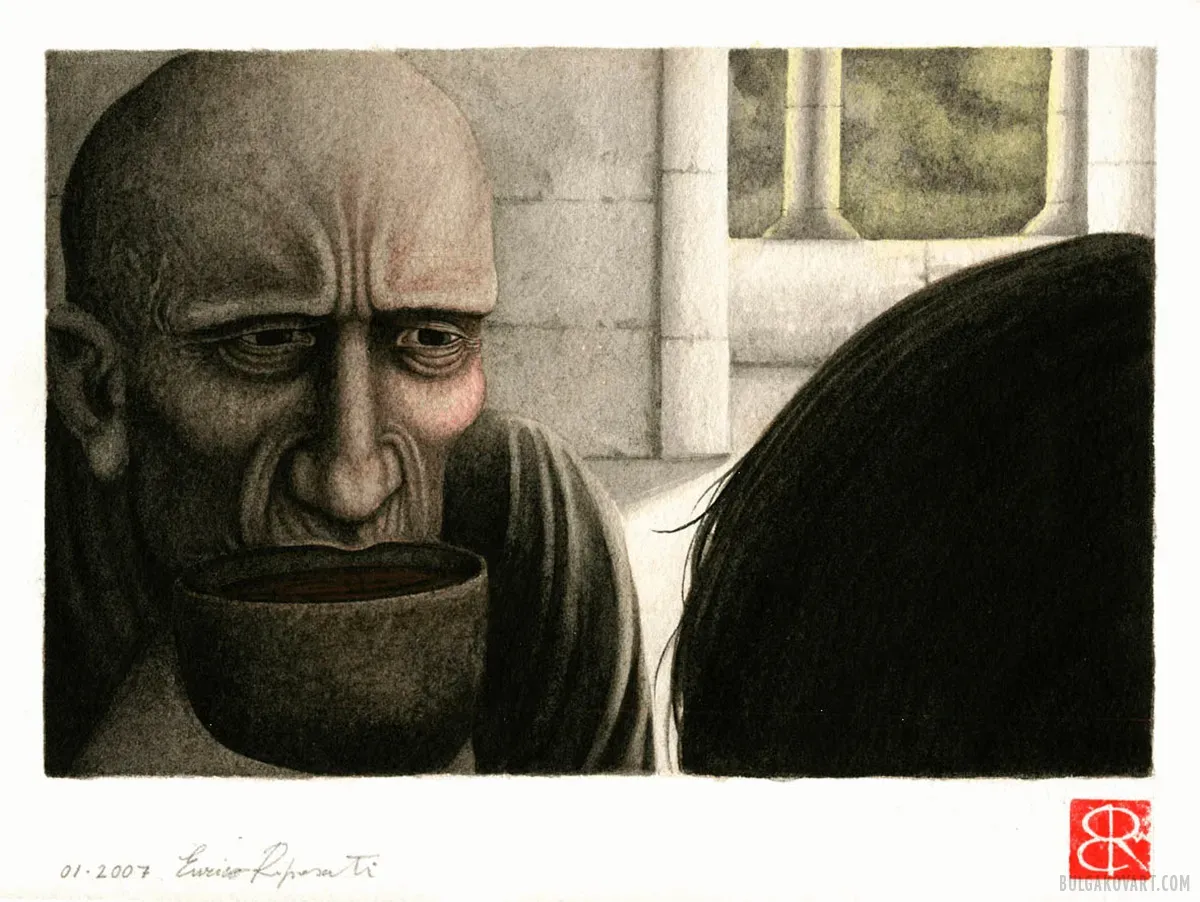

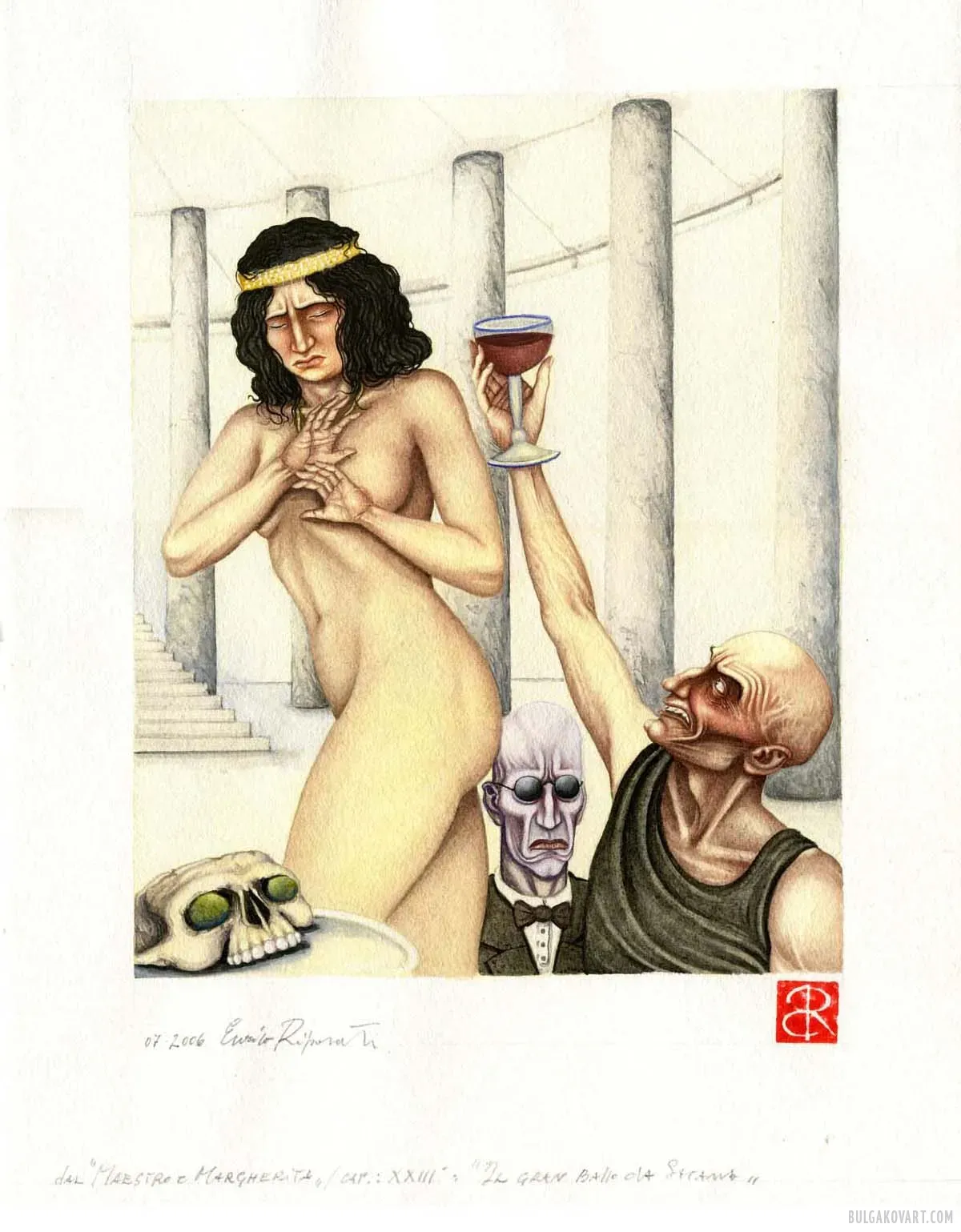

The one who had arrived did not refuse a second cup of wine either:

“An excellent vintage, procurator, but this is not Falernian?”

“Caecuban, thirty years old,” the procurator replied amiably.

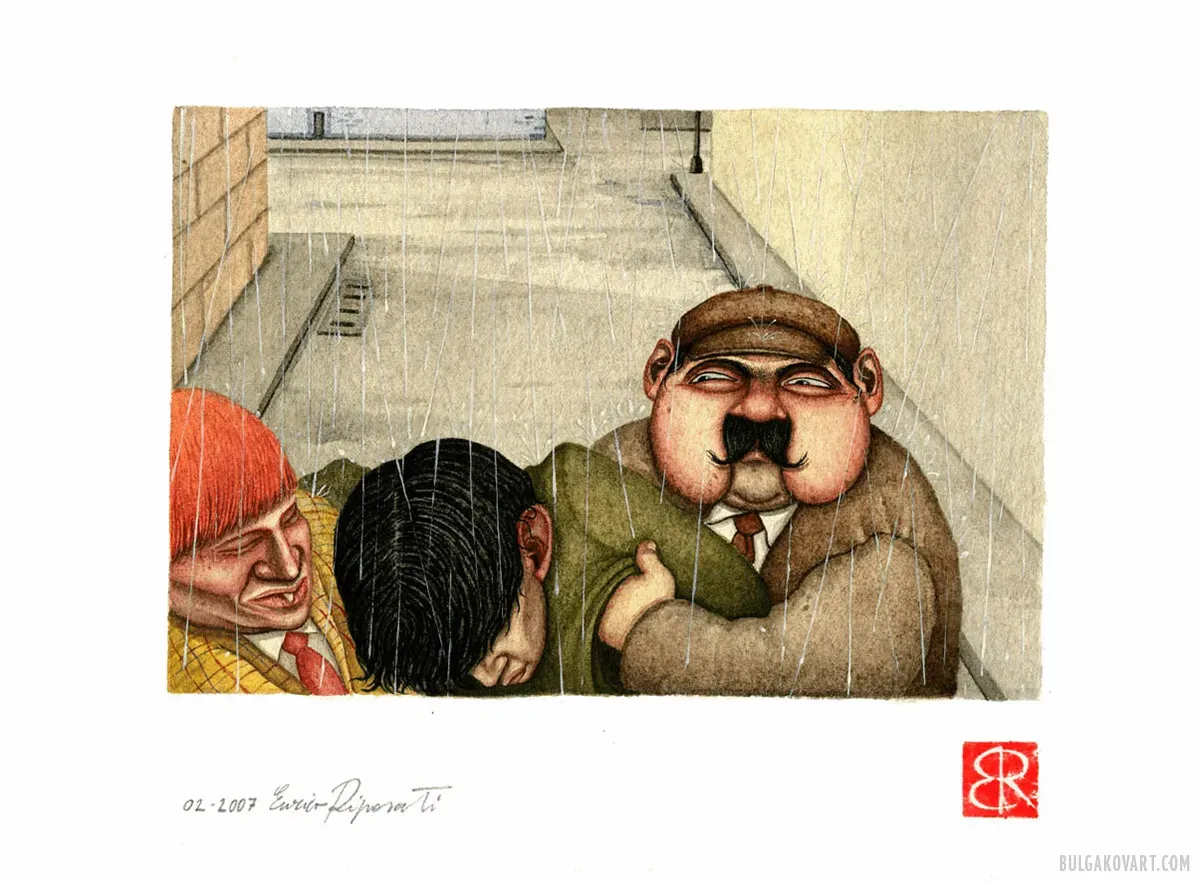

Both of them took the administrator by the arms, dragged him out of the garden, and raced with him down Sadovaya Street. The thunderstorm raged at full force, water roared and howled as it fell into the sewer holes, there were bubbles everywhere, waves swelled, water lashed off the roofs past the pipes, and foamy streams ran from the archways. All living things were washed away from Sadovaya, and there was no one to save Ivan Savelyevich.

“Azazello, see him out!” ordered the cat and left the antechamber. The one named Azazello lifted the suitcase with one hand, flung open the door with the other, and, taking Berlioz's uncle by the arm, led him out onto the landing.

And at that moment, a joyful, unexpected cry of a rooster flew in from the garden. Wild rage contorted the girl's face; she let out a hoarse curse, and Varenukha at the door shrieked and fell from the air to the floor.

The beautiful secretary shrieked and, wringing her hands, cried out: “Do you see? Do you see?! He's not there! He's not there! Bring him back, bring him back!”

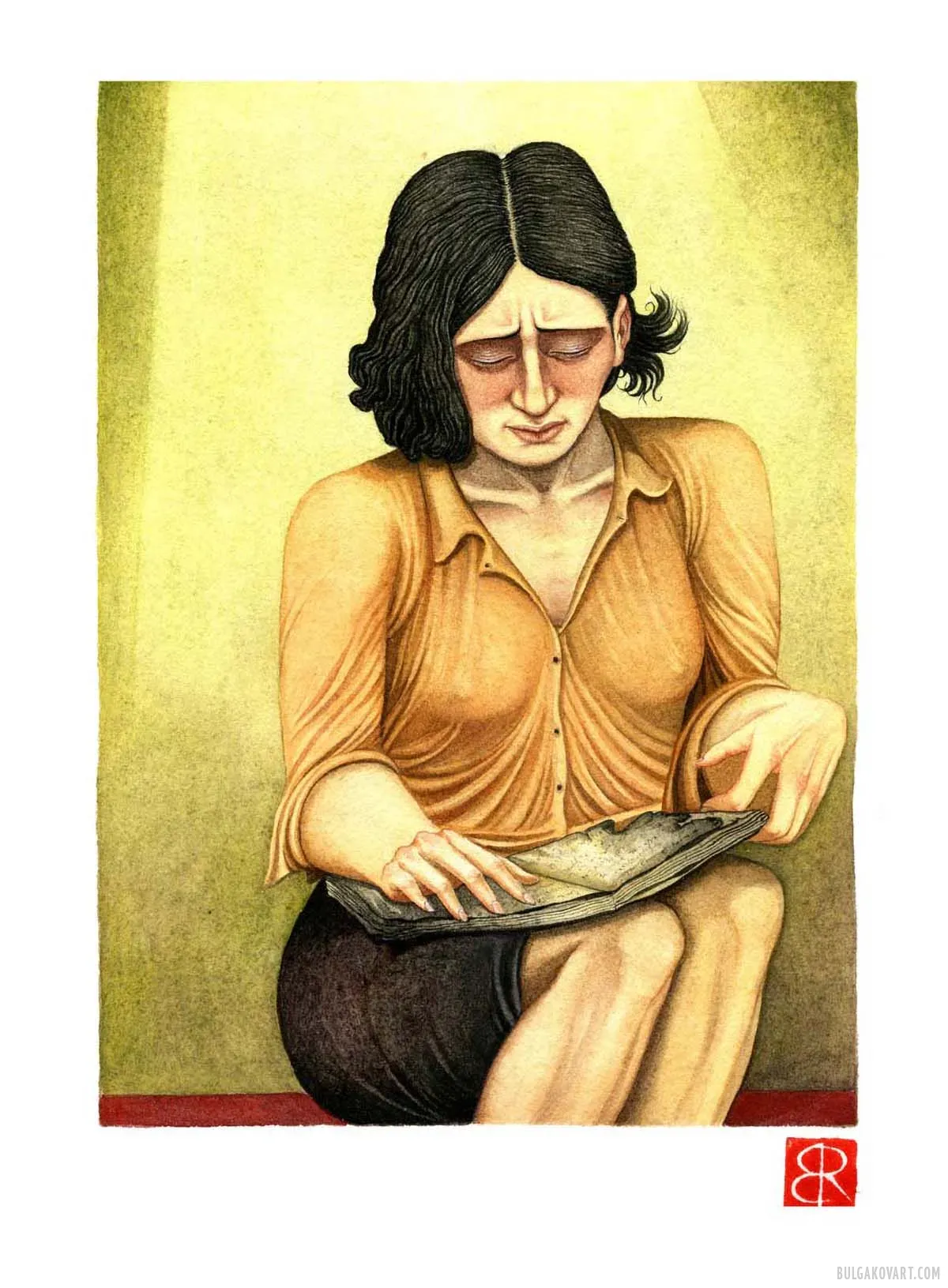

Margarita Nikolaevna placed a photograph on the three-paneled mirror and sat for about an hour, holding the fire-damaged notebook on her lap, flipping through it and rereading that which, after being burned, had neither a beginning nor an end.

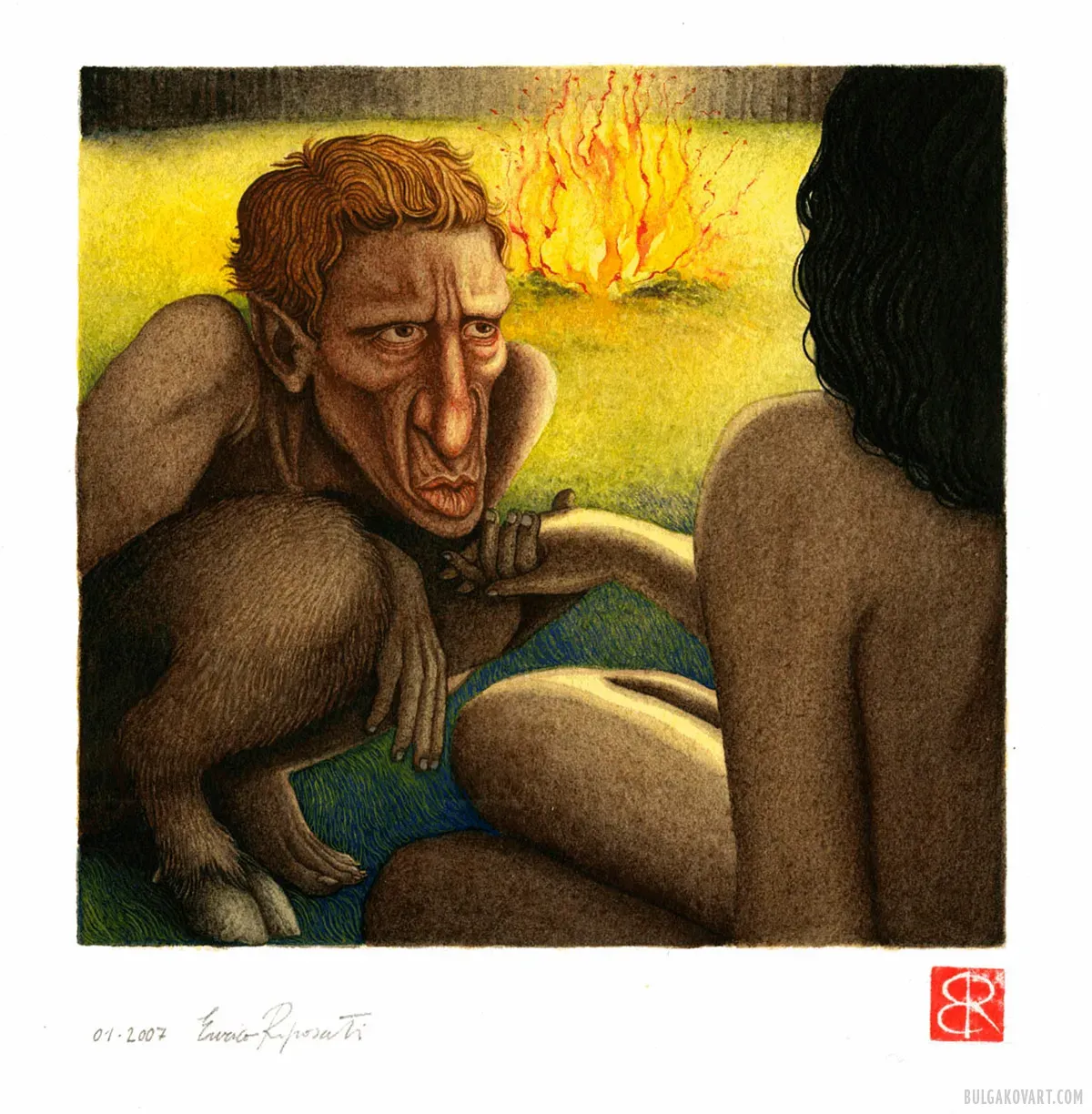

Someone with goat legs flew over and clasped her hand, spread silk on the grass, inquiring whether the queen had bathed well, and offered her a place to lie down and rest.

Woland's face was slanted to one side, the right corner of his mouth was pulled down, and on his high, bald forehead were deep wrinkles running parallel to his sharp eyebrows. Margarita also made out on Woland's exposed, hairless chest a beetle skillfully carved from dark stone on a gold chain and with some sort of writing on its back.

Woland quickly approached Margarita, brought a chalice to her, and said commandingly: “Drink!”

From the windowsill, a greenish shawl of night light fell onto the floor, and in it appeared Ivanushka's nocturnal guest, who called himself the Master. Margarita recognized him immediately, moaned, clasped her hands, and ran to him. She kissed him on the forehead, on the lips, pressed against his prickly cheek, and her long-held tears now streamed down her face.

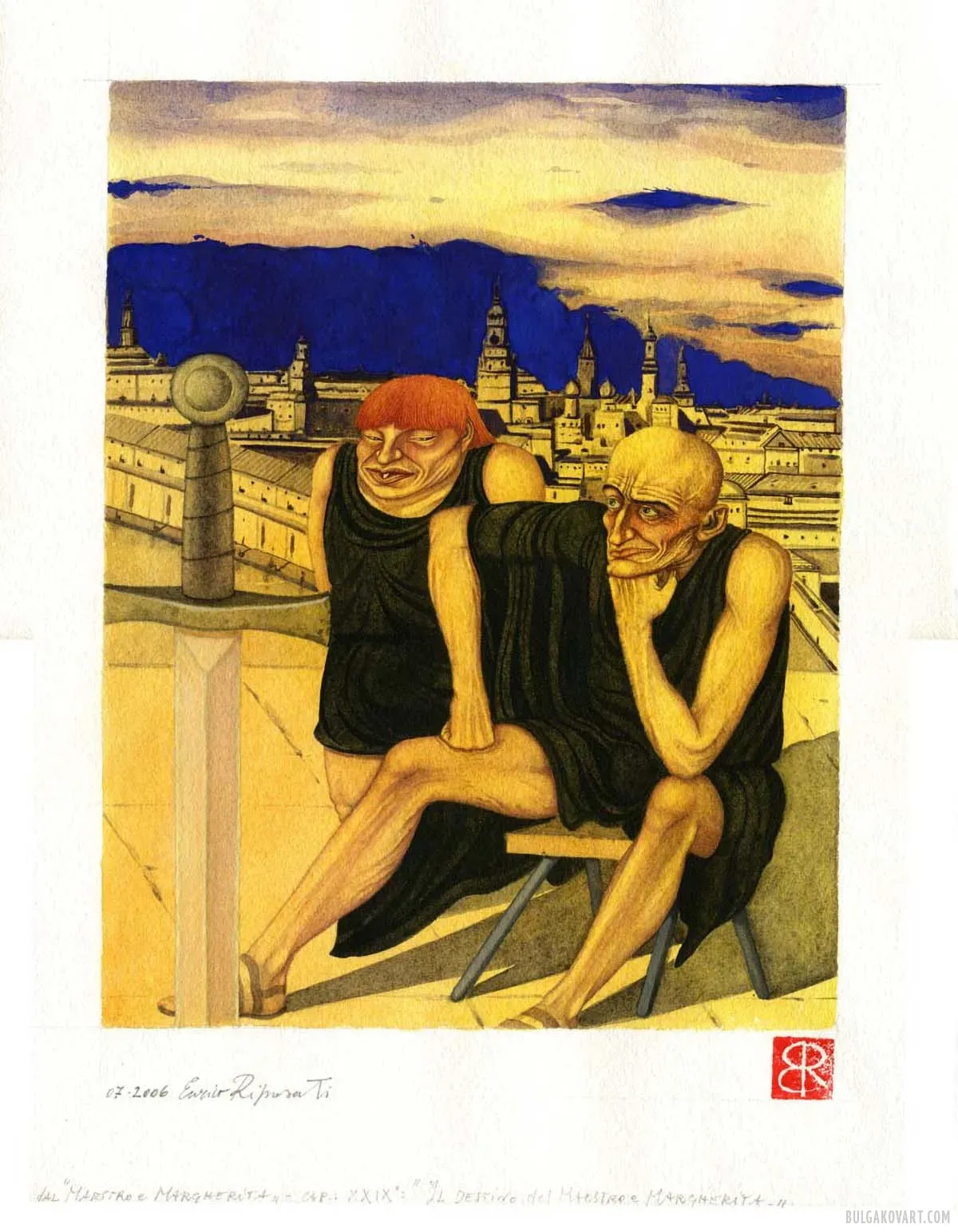

Woland sat on a folding stool, dressed in his black cassock. His long, broad sword was thrust between two cracked terrace slabs. Resting his sharp chin on his fist, hunched over on the stool and tucking one leg under himself, Woland looked unblinkingly at the immense conglomeration of palaces, giant houses, and small hovels doomed to demolition.

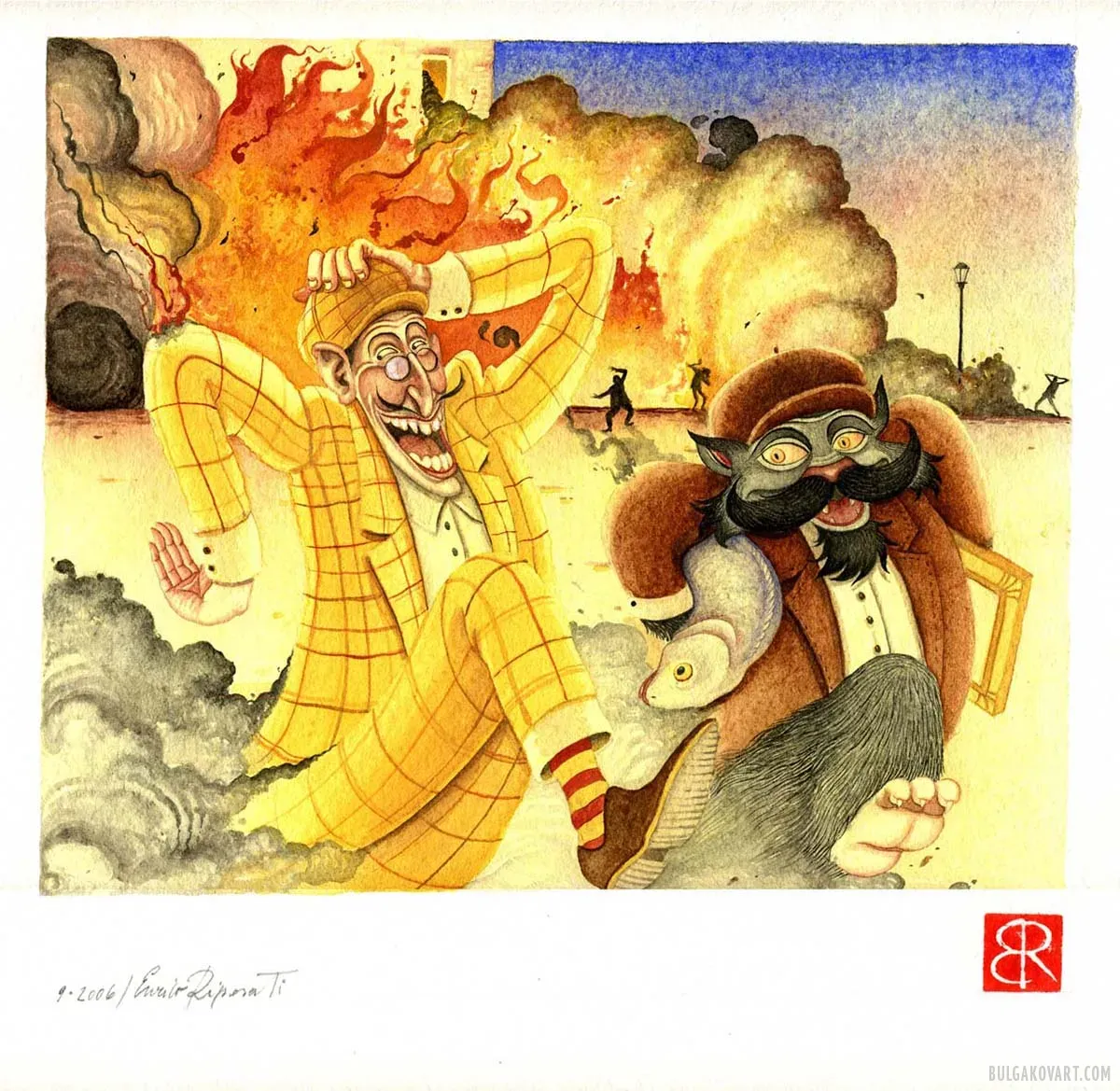

“Mad with fear, Behemoth and I rushed to run to the boulevard, the pursuers after us, we rushed to Timiryazev monument!”

“But the sense of duty,” Behemoth interjected, “overcame our shameful fear, and we returned!”

“Ah, you returned?” Woland said, “Well, of course, then the building burned to the ground.”

Three black horses snorted by the shed, shuddered, and exploded the earth in fountains. Margarita leaped on first, followed by Azazello, with the Master last.

The night thickened, flew alongside, grabbing the riders by their cloaks and, tearing them from their shoulders, exposed the deceits. And when Margarita, fanned by the cool wind, opened her eyes, she saw how the appearance of all those flying to their destination was changing.

The mountains turned the Master's voice into thunder, and this same thunder destroyed them. The accursed rocky walls fell. Only the platform with the stone chair remained. Above the black abyss into which the walls had gone, an immense city lit up with its sparkling idols reigning over it, above a garden that had grown luxuriantly over many thousands of these moons.