These works are currently, perhaps, the most famous photographic embodiment of the novel (at least abroad; in Russia, photos by Retro-Atelier or Elena Martynuk could certainly compete).

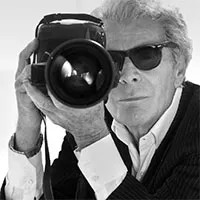

The project was conceived in 2008 by Evgeny Yakovlev, a businessman and a great admirer of Bulgakov's novel. He proposed it to Jean-Daniel Lorieux, a Vogue magazine photographer and one of the most famous photographers in France, a legend in the world of fashion photography, as well as a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour and the Order of Arts.

The role of Margarita was given to Isabelle Adjani. The other actors were predominantly Russian (and the project's producer, Evgeny Yakovlev, even played the knight).

So, let's take a look at the results. I have tried to select the most suitable quotes from the novel for each photograph.

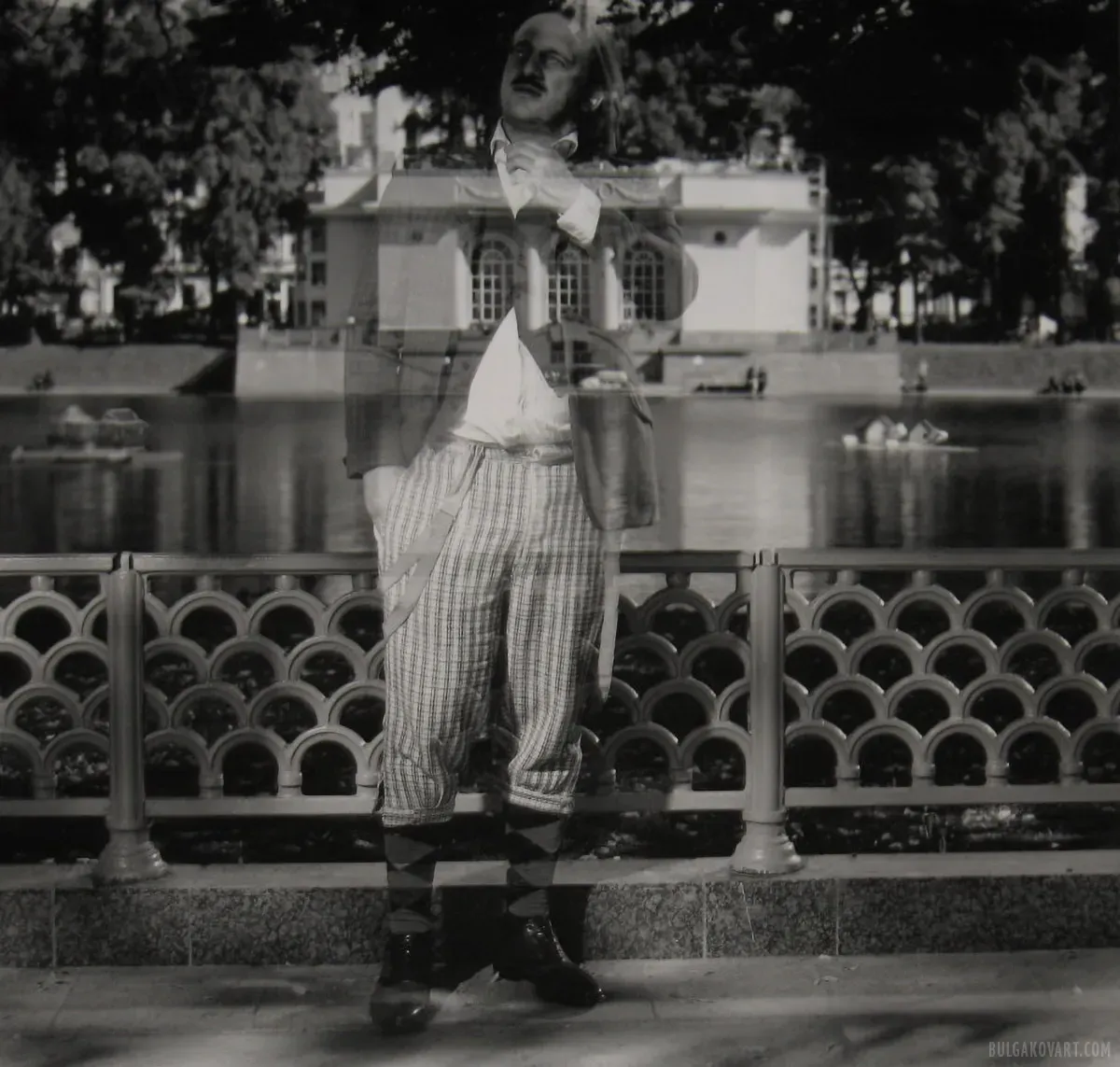

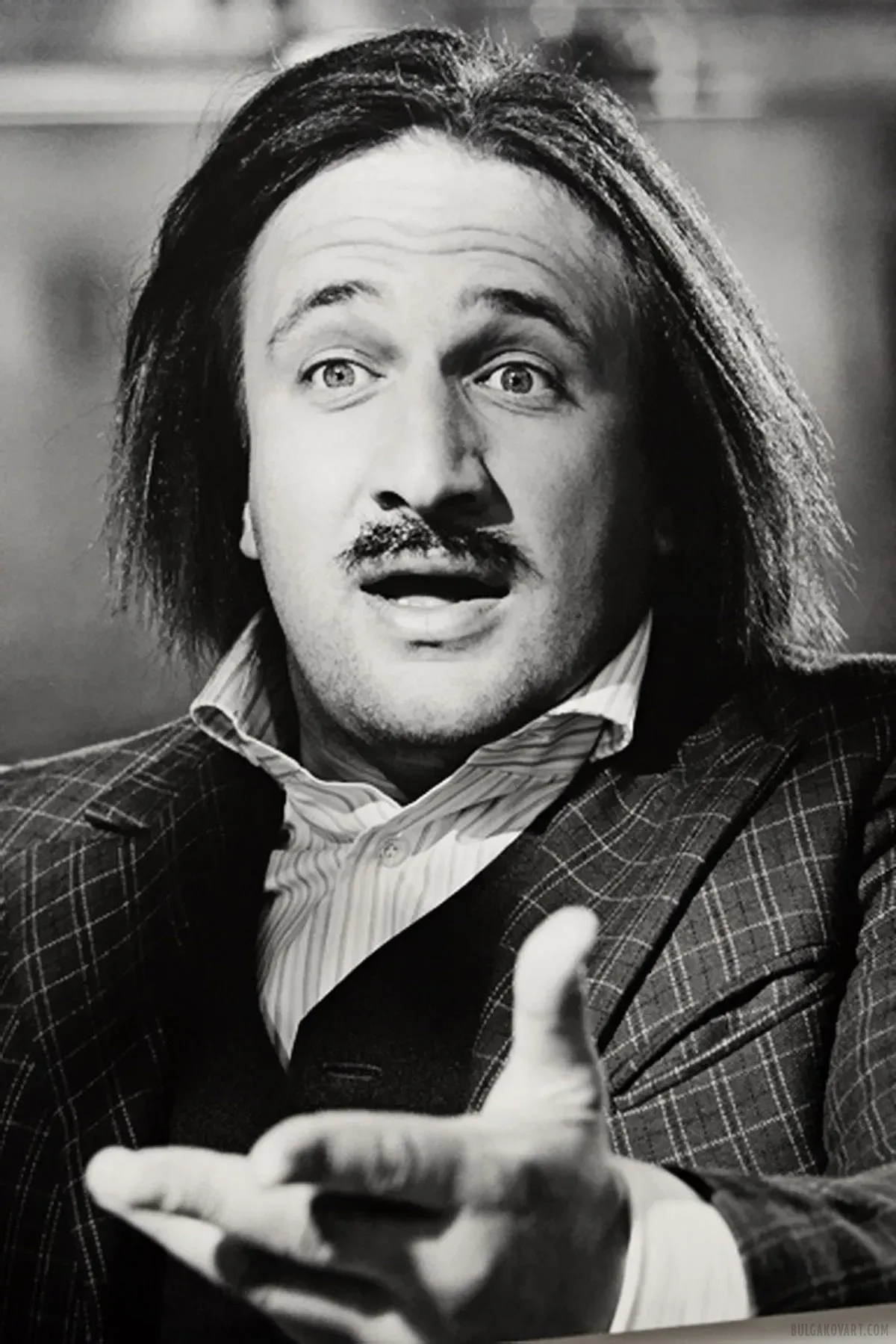

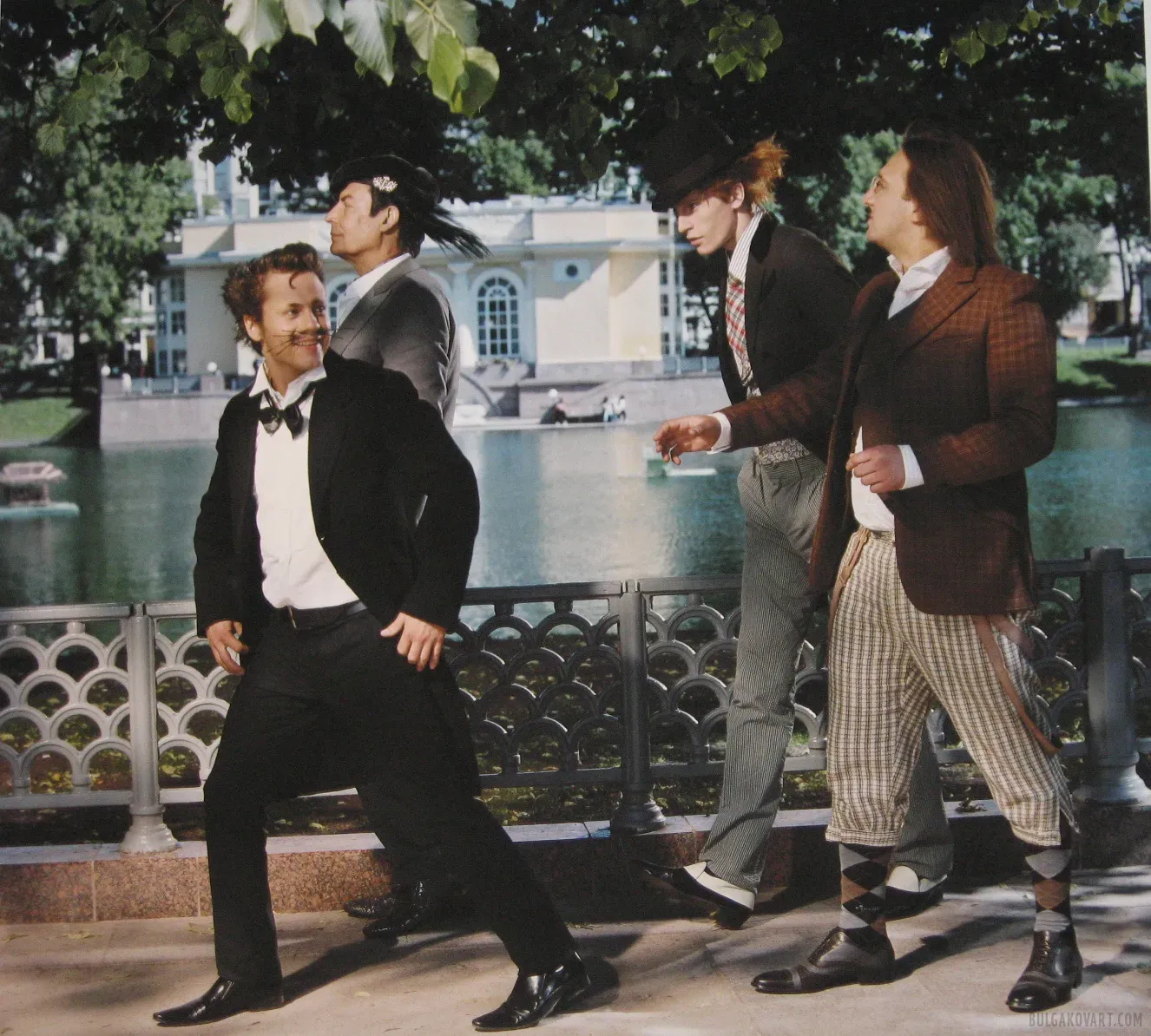

And then the sultry air congealed before him, and out of this air a citizen of a most strange appearance was woven. On his small head was a jockey's cap, a checkered, short, and airy jacket... The citizen was as tall as a fathom, but narrow in the shoulders, incredibly thin, and his face, mind you, was mocking.

“In our country, atheism surprises no one,” Berlioz said diplomatically and politely, “the majority of our population has consciously and long ago stopped believing in fairy tales about God.”

“And the devil is not there either?” the patient suddenly asked Ivan Nikolaevich cheerfully.

“And the devil...”

Here the madman burst out laughing so loudly that a sparrow flew out of the linden tree above the heads of those sitting.

“There is no devil!” Ivan Nikolaevich cried out, confused by all this nonsense.

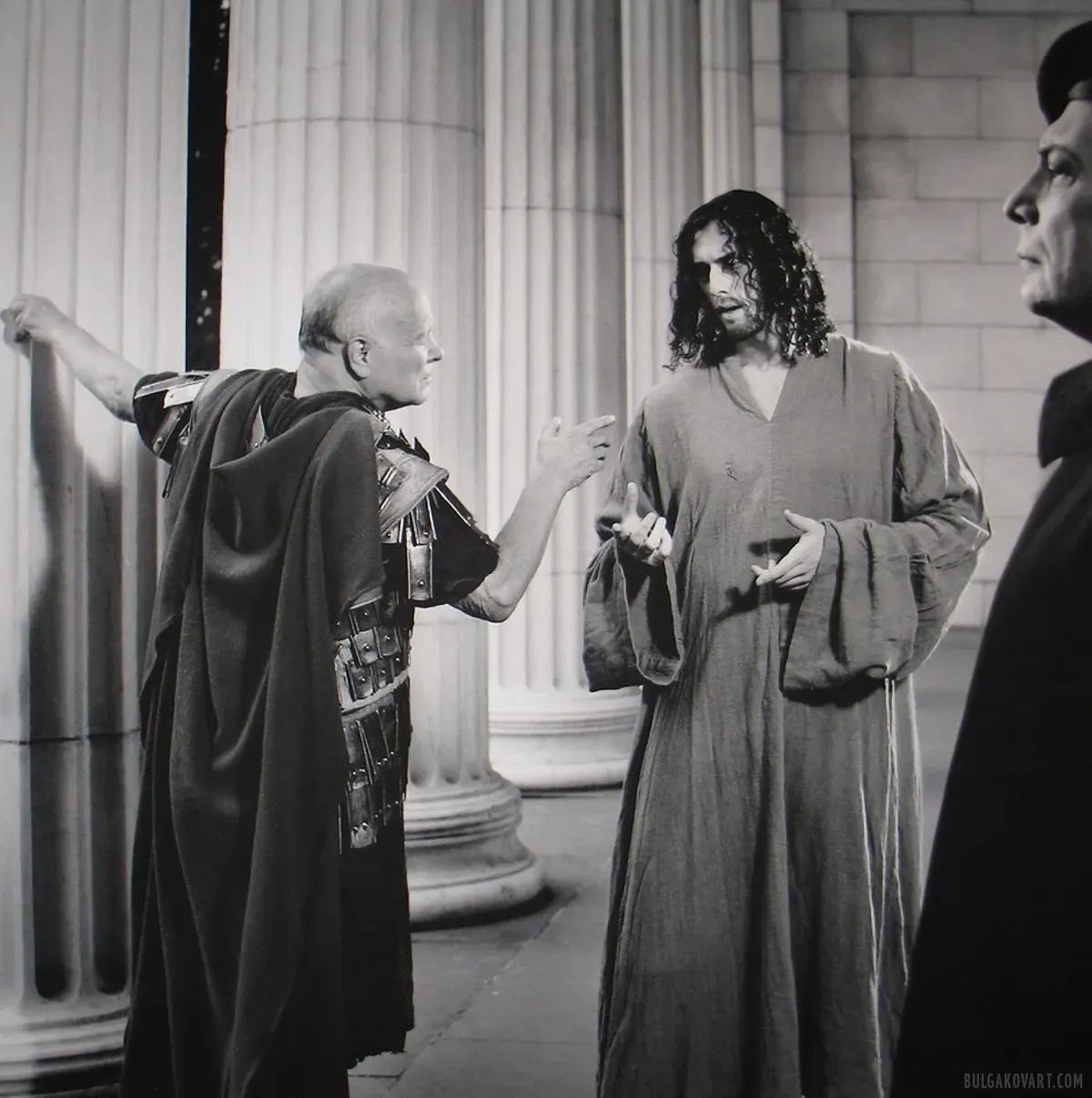

“The fact is, I was personally present at all of this. Both on the balcony of Pontius Pilate and in the garden when he was talking to Caiaphas, and on the platform, but secretly, incognito, so to speak.”

“Looking for the turnstile, citizen?” the checkered guy inquired in a cracked tenor, “This way please! Straight ahead, and you'll get out where you need to. For giving you directions, I could use a quarter-liter... to get better... a former choirmaster!”

The third in this company was a cat that appeared out of nowhere.

The three moved towards Patriarch's Lane, and the cat started to move on his hind legs.

Ivan rushed after the villains and immediately realized that it would be very difficult to catch them.

Ivan focused his attention on the cat.

The strange cat walked up to the running board of the A-line motor tram, which was at a stop, impudently nudged a shrieking woman aside, grabbed onto the railing, and even tried to hand a dime to the conductress through the open window, as it was stuffy.

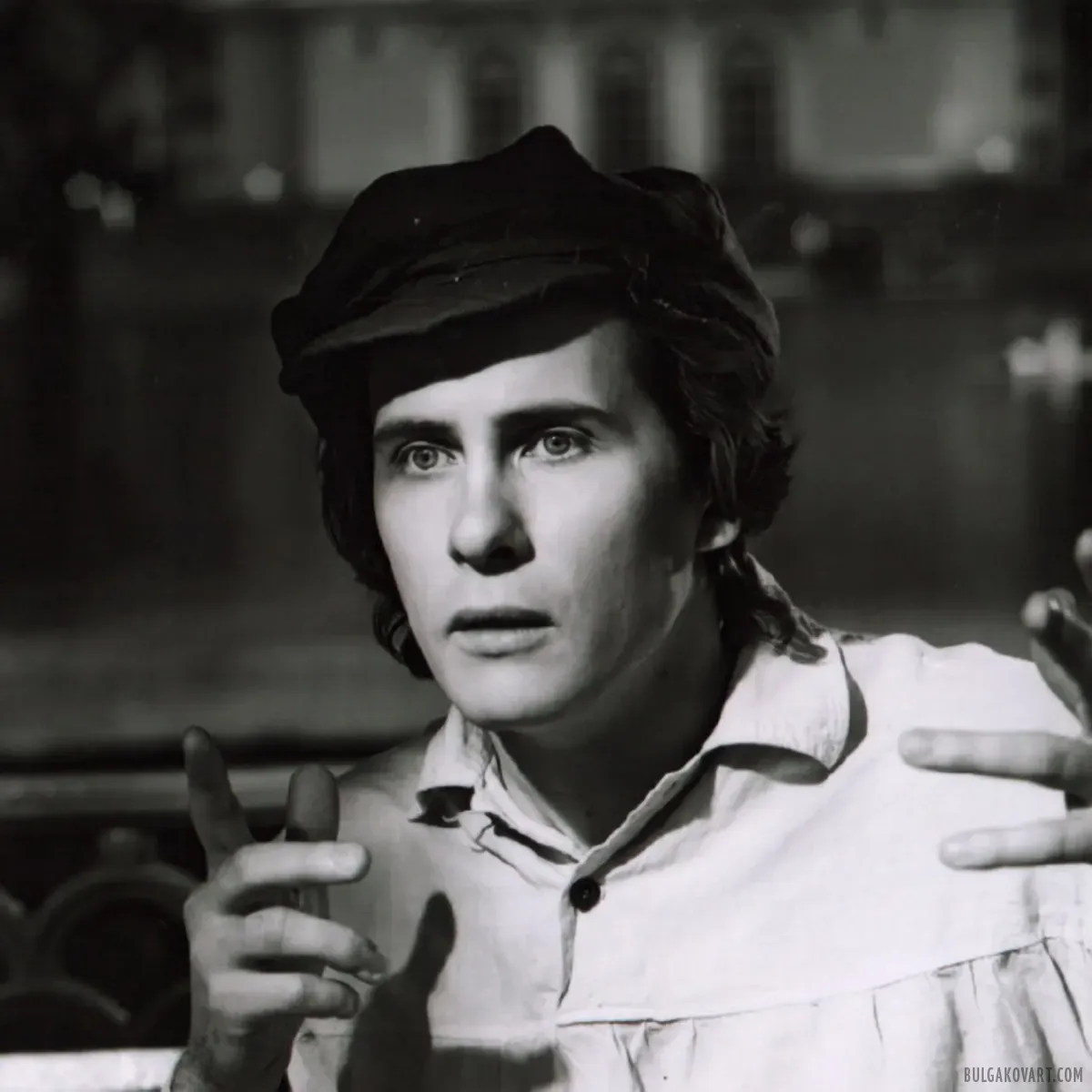

Here everyone saw that this was not a ghost, but Ivan Nikolaevich Bezdomny, a famous poet. He was barefoot, wearing a torn whitish sweatshirt, to which a paper icon with a faded image of an unknown saint was pinned to his chest with a safety pin, and in striped white underpants. In his hand, Ivan Nikolaevich carried a lit wedding candle.

“Pilate was flying towards the end, towards the end, and I already knew that the last words of the novel would be: “... the fifth procurator of Judea, the equestrian Pontius Pilate.” Well, naturally, I went out for a walk. I had a wonderful gray suit...”

“Thousands of people were walking along Tverskaya, but I assure you, she saw only me and looked not so much anxious as even a little pained.”

“She carried in her hands some repulsive, disturbing yellow flowers. The devil knows what they're called, but for some reason, they are the first to appear in Moscow. And these flowers stood out very distinctly against her black spring coat.”

“And I was struck not so much by her beauty as by the extraordinary, unseen-by-anyone loneliness in her eyes!”

She promised glory, she urged him on, and that's when she started calling him a master. She waited for those promised last words about the fifth procurator of Judea, chanted and loudly repeated individual phrases that she liked, and said that her life was in this novel.

The one who called himself the Master worked, and she, running her thin fingers with sharply pointed nails through her hair, would reread what was written, and after rereading it, she would sew this very cap.

With a quiet cry, she threw the last thing that was left in the stove onto the floor with her bare hands, a pack that had caught fire from below.

Margarita Nikolaevna sat for about an hour, holding the notebook ruined by the fire on her knees, leafing through it and rereading what had no beginning or end after the burning.

The surprised Margarita Nikolaevna turned around and saw a citizen on her bench, who had obviously quietly sat down while Margarita was gazing at the procession.

This companion turned out to be short, fiery red-haired, with a fang, in starched linen, in a good striped suit, in patent leather shoes and with a bowler hat on his head. The tie was bright. What was surprising was that from the pocket where men usually carry a handkerchief or a fountain pen, this citizen had a gnawed chicken bone sticking out.

“Then please receive this,” said Azazello, and taking a round golden box from his pocket, he held it out to Margarita with the words: “Now, hide it, or the passersby will see. It will come in handy for you, Margarita Nikolaevna. You've aged a great deal from grief over the last six months.”

Margarita was silent for a moment, then replied:

„I understand. This thing is pure gold, I can tell by the weight. Well, I perfectly understand that I am being bribed and pulled into some murky business for which I will pay dearly.“

Margarita Nikolaevna was sitting in front of the dressing table in a bathrobe thrown over her naked body. A gold bracelet with a watch lay in front of Margarita Nikolaevna next to the box she had received from Azazello, and Margarita did not take her eyes off the dial.

At times it began to seem to her that the clock was broken and the hands were not moving.

After applying the cream a few times, Margarita glanced in the mirror and dropped the box right onto the watch glass, causing it to crack.

Her eyebrows, plucked into a thin thread, thickened and lay in smooth black arches over her now green eyes. The thin vertical wrinkle that had cut across the bridge of her nose vanished without a trace. The yellowish shadows at her temples and the two barely noticeable networks of lines at the outer corners of her eyes also disappeared. The skin on her cheeks took on an even rosy color, her forehead became white and clear, and her permed hair straightened.

Margarita pulled the curtain aside and sat sideways on the windowsill, clasping her knee with her hands. The moonlight licked her right side. Margarita raised her head to the moon and made a thoughtful and poetic face.

Invisible and free!

“What amazes me most is where all this fits,” she said, waving her hand, emphasizing the vastness of the room.

Some force jerked Margarita up and placed her in front of the mirror, and in her hair, a royal diamond crown glittered.

“Where are the guests?” Margarita asked Koroviev.

“They will be here, Queen, they will be here soon. There will be no shortage of them. And, really, I would prefer to chop wood instead of receiving them here on the platform.”

Now a stream of people was rising up the stairs from below. Margarita stopped seeing what was happening in the antechamber. She mechanically raised and lowered her hand and, with a monotonous baring of her teeth, smiled at the guests.

“Ah, how pleasant it is to have dinner just like this, by the fireplace, simply,” Koroviev chirped, “in a close circle.”

(I don’t remember anything like this in the novel, but what difference does it make?)

“What are those footsteps on the stairs?” Koroviev asked.

“They're coming to arrest us,” Azazello replied.

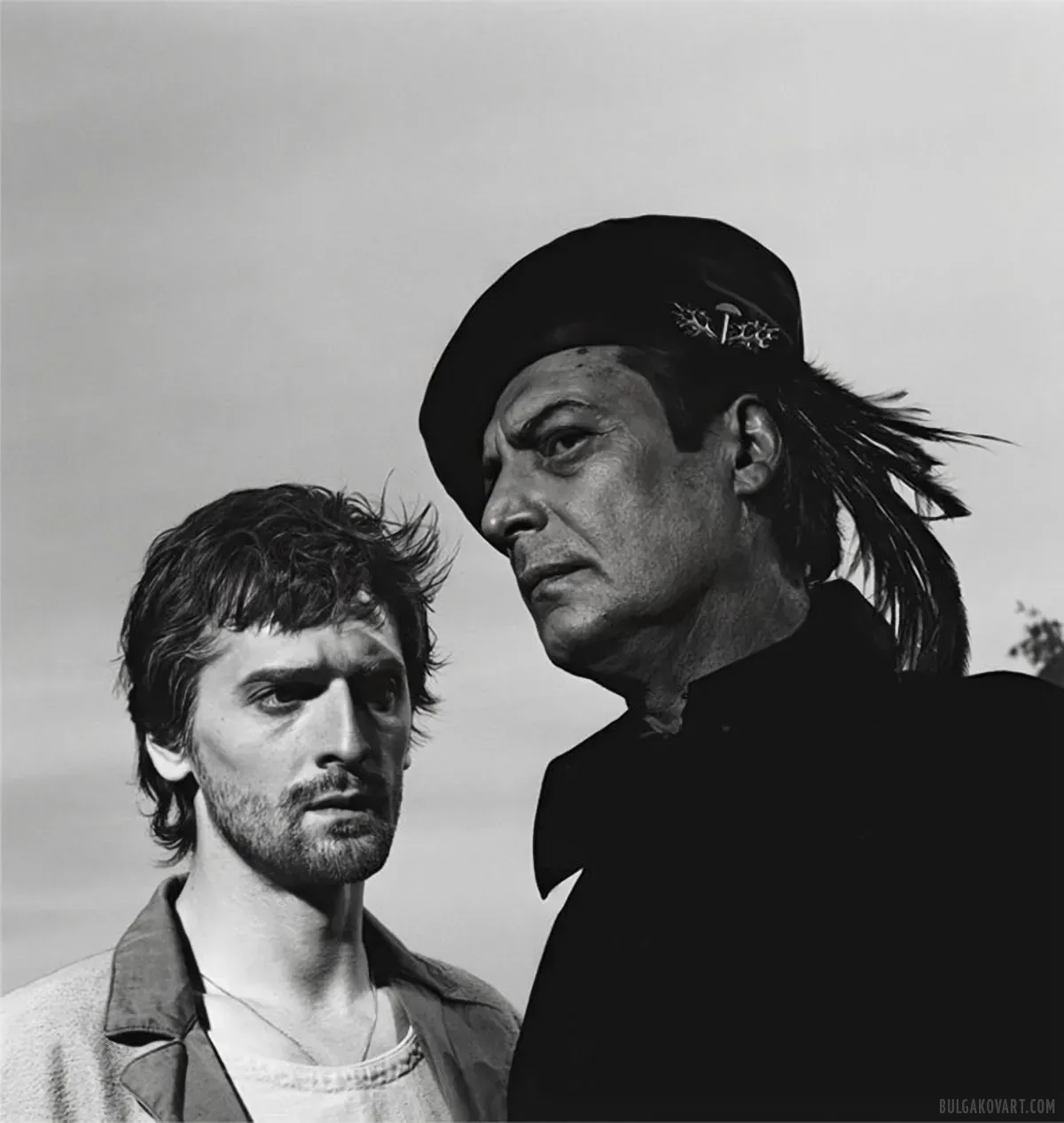

At sunset, high above the city, on the stone terrace of one of the most beautiful buildings in Moscow, a building built about one hundred and fifty years ago, there were two people: Woland and Azazello.

Resting his sharp chin on his fist, hunched over on a stool with one leg tucked under him, Woland stared without interruption at the immense collection of palaces, giant houses, and small, condemned-to-demolition shacks.

“I ask you to note that this is the very wine that the procurator of Judea drank. Falernian wine.”

The deceased's face brightened and finally softened, and her grin became not predatory, but simply a feminine, suffering grin.

“Well then,” Woland addressed him from the height of his horse, “are all the bills paid? Has the farewell taken place?”

“Yes, it has taken place,” the master answered and, having calmed down, looked straight and boldly into Woland's face.

The night grew thicker, flew alongside, grabbed the galloping ones by their cloaks and, tearing them off their shoulders, exposed their deceptions. And when Margarita, blown by the cool wind, opened her eyes, she saw how the appearance of all those flying to their goal changed.

When a crimson and full moon began to emerge from behind the edge of the forest to meet them, all the deceptions disappeared, the magical, unstable clothing fell into the swamp and drowned in the fog.

Koroviev-Fagott, the self-proclaimed interpreter for the mysterious consultant who didn't need translations, would hardly have been recognizable now in the one who was flying directly with Woland on the right hand of the Master's friend. In the place of the one who had left Sparrow Hills in torn circus clothes under the name of Koroviev-Fagott, a dark-violet knight with a somber and never-smiling face now galloped, his golden bridle chain quietly jingling.

“This knight once made an unsuccessful joke,” answered Woland, turning his face with a quietly burning eye to Margarita, “his pun, which he composed, talking about light and darkness, was not very good. And after that the knight had to joke a little more and longer than he had expected. But today is the night when scores are settled. The knight paid his bill and closed it!”

Azazello flew alongside them all, his armor shining with steel. The moon had changed his face too. The ridiculous, ugly fang had disappeared without a trace, and his crooked eyes had turned out to be false. Both of Azazello's eyes were identical, empty and black, and his face was white and cold. Now Azazello flew in his true form, like a demon of a waterless desert, a demon-killer.

Above the black abyss into which the walls had sunk, a vast city lit up with glittering idols reigning over it, above a garden that had grown luxuriantly over many thousands of these moons. The long-awaited moon road stretched straight to this garden, and the first to run along it was a sharp-eared dog.