In 2001, the publishing house Intrade Corporation released a gift edition containing an illustrated novel The White Guard, with illustrations by a group of five artists: V. Prokofiev, B. Barulin, V. Glushenko, G. Yudin, and A. Samorezov.

You can, by the way, find and buy the book online.

Portrait of the author

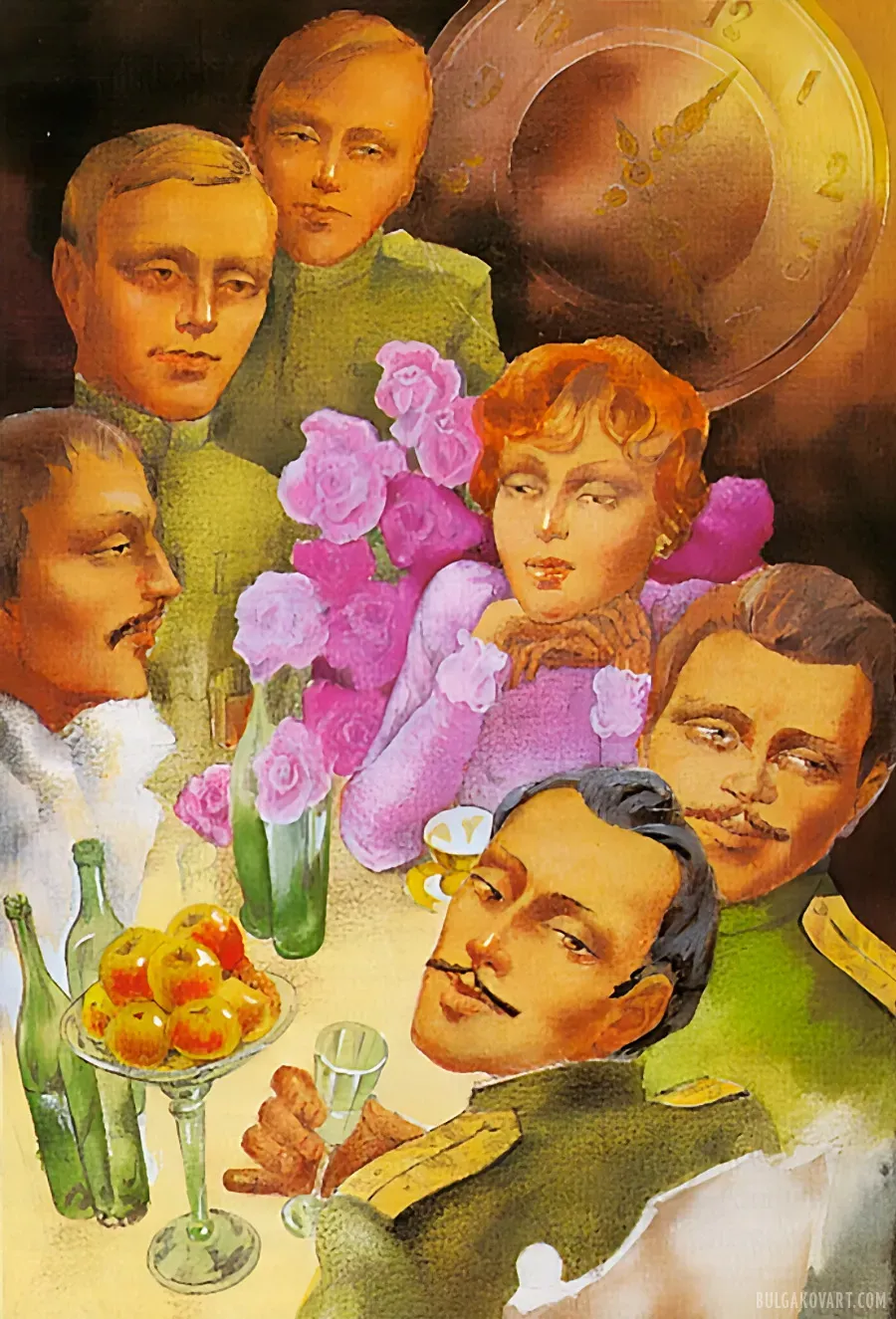

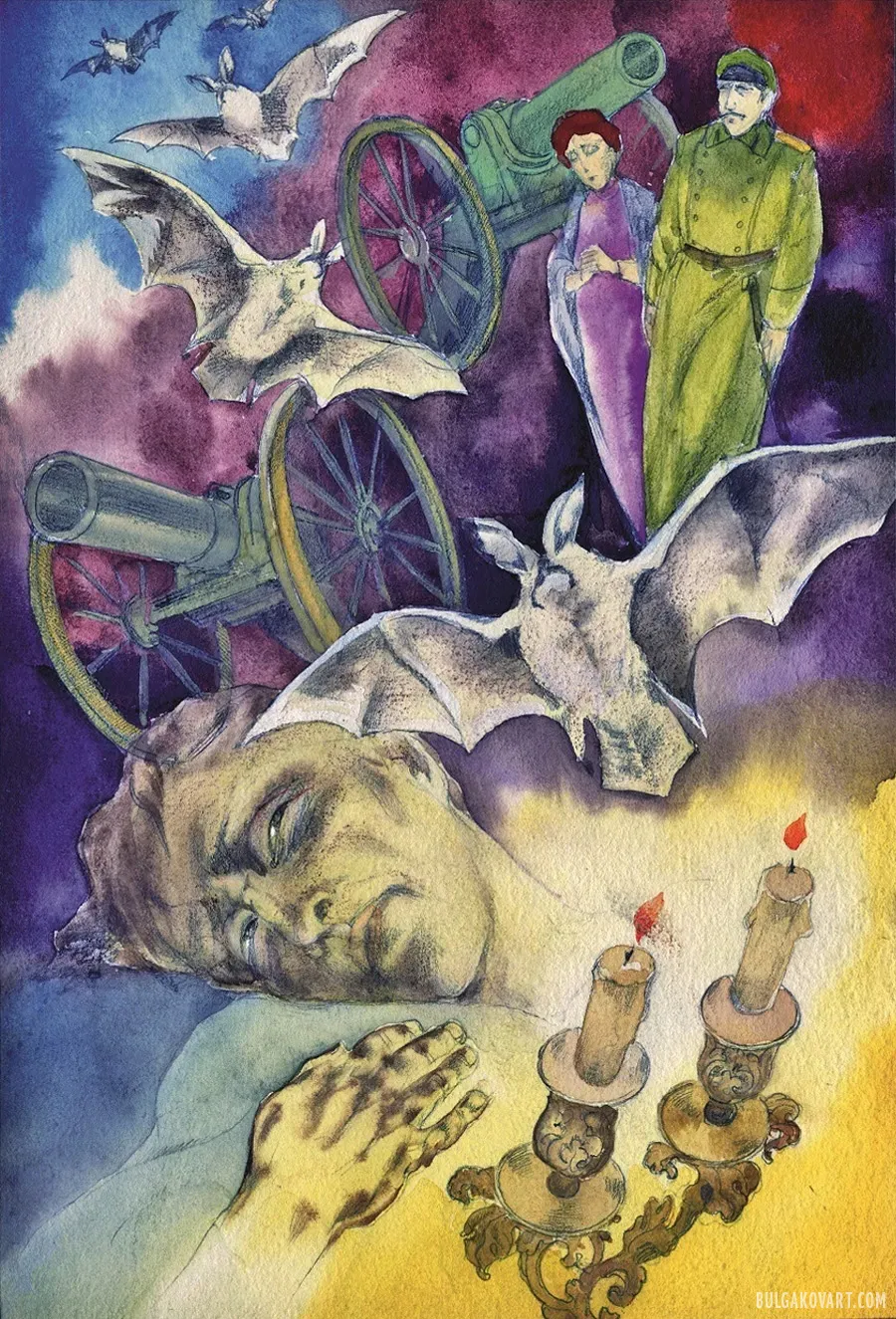

The front door let in the cold, and before Alexey and Elena appeared a tall, broad-shouldered figure in a floor-length greatcoat and protective epaulets with three lieutenant's stars drawn on with a chemical pencil. His bashlyk was covered in hoarfrost, and a heavy rifle with a brown bayonet took up the entire hallway.

Myshlayevsky, somewhere behind a curtain of smoke, burst out laughing. He was drunk.

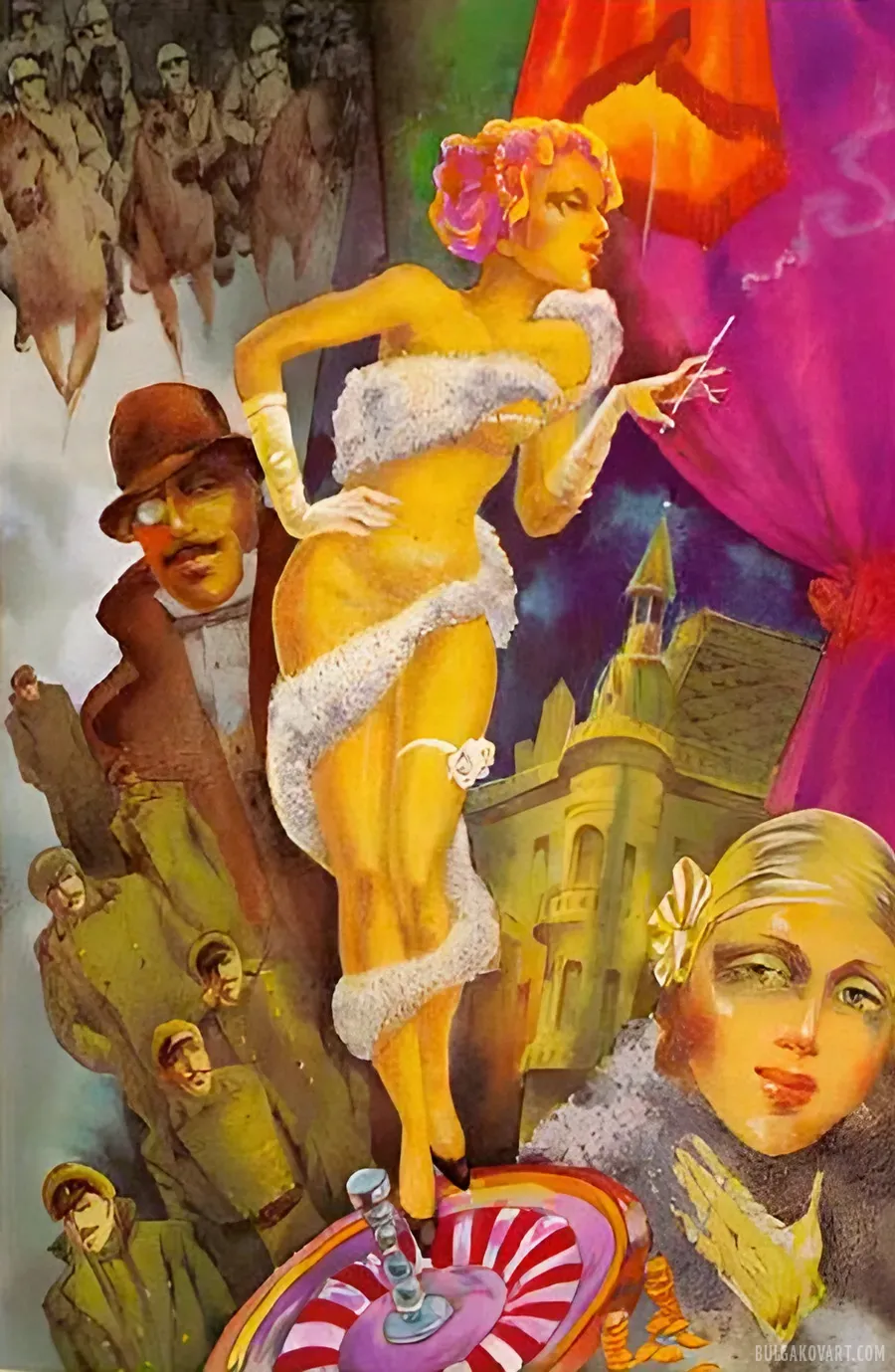

And so, in the winter of 1918, the City lived a strange, unnatural life that might never be repeated in the twentieth century. Its ancient, native inhabitants huddled together and continued to shrink, willingly or unwillingly letting in the new arrivals who flocked to the City. The City swelled, widened, and rose like dough from a pot. Gambling clubs rustled until dawn, and inside them, people from Petersburg and locals played, as did important and proud German lieutenants and majors whom the Russians feared and respected. The ceiling spread out like a star of blue dusty silk, large diamonds sparkled in the blue boxes, and reddish Siberian furs gleamed. And it smelled of burnt coffee, sweat, alcohol, and French perfume.

“To die—it's not like playing tag,” Colonel Nai-Turs, who had appeared from who knows where before the sleeping Alexey Turbin, suddenly said with a lisp. He was in a strange uniform: a radiant helmet on his head, a coat of mail on his body, and he was leaning on a long sword, the likes of which no longer exist in any army since the Crusades. A heavenly glow followed Nai like a cloud.

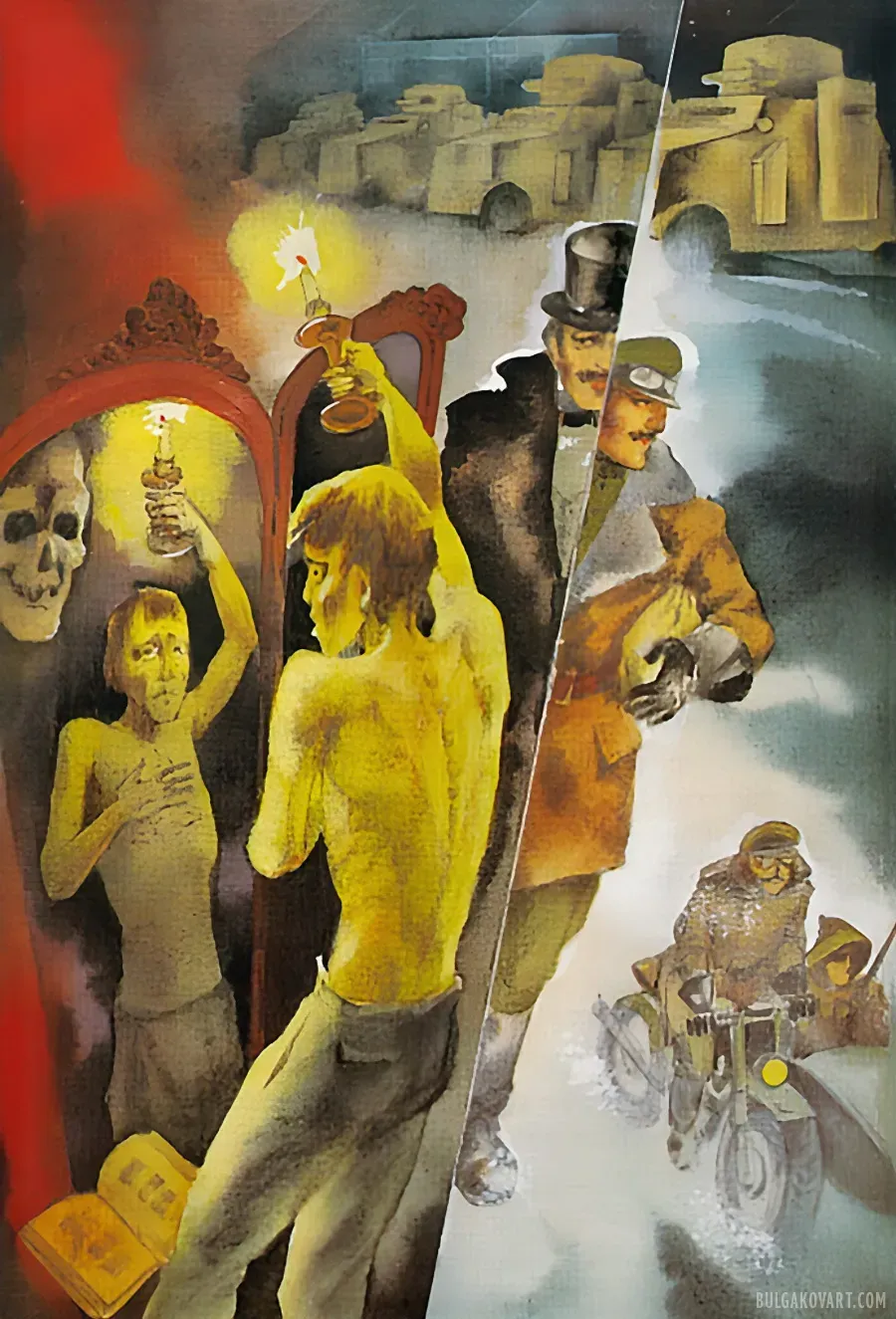

Some kind of strange, indecent bustle in the palace at night. A thin, graying man with a trimmed mustache on a shaven, foxy, parchment face, dressed in a rich Circassian coat with silver cartridges, scurried back and forth by the mirrors. Three German officers and two Russians stirred around him.

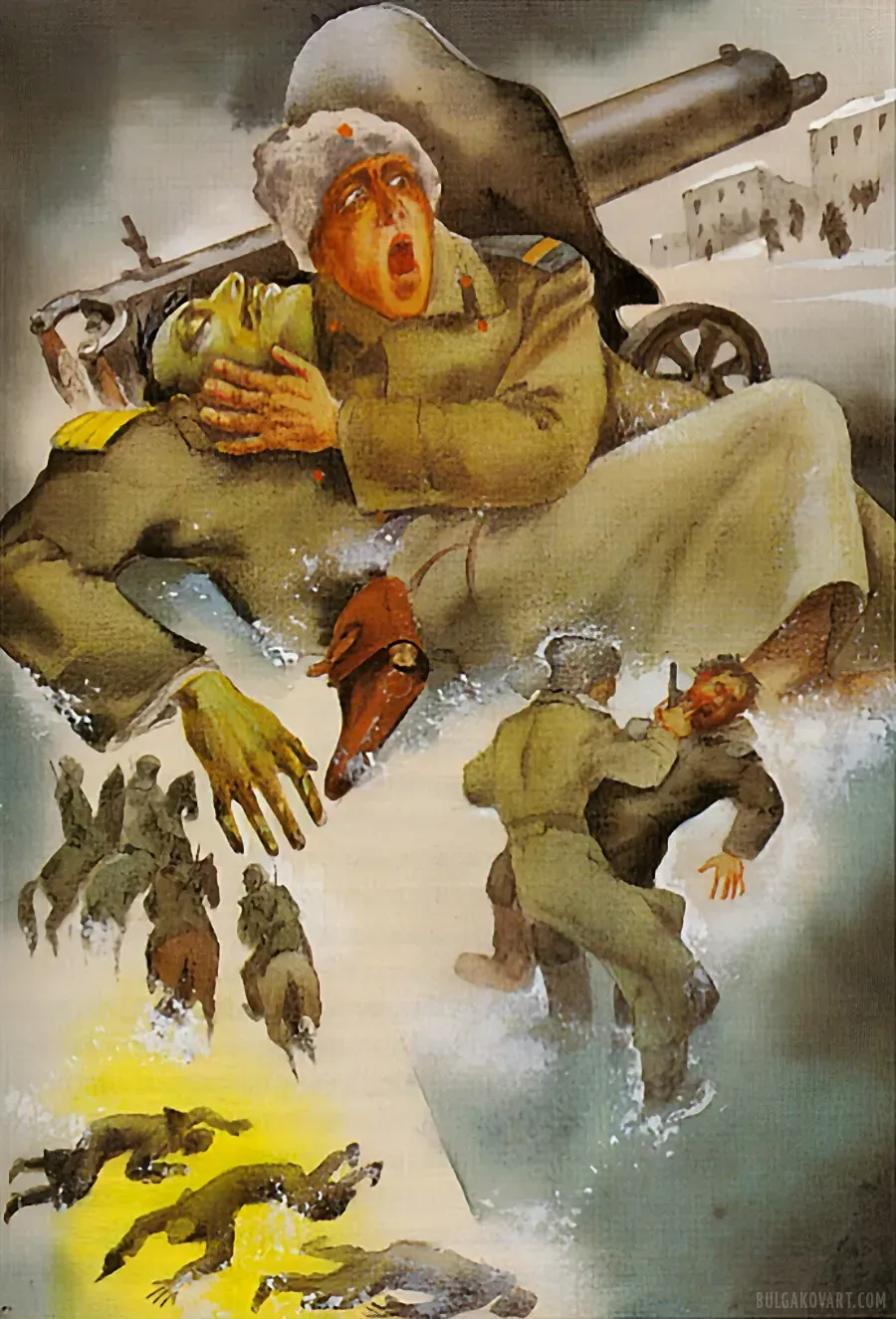

“Division, attention!” he suddenly roared, so that the division instinctively flinched. “The Hetman, at about four o'clock this morning, shamefully abandoned all of us to our fate and fled! In no more than a few hours, we will witness a catastrophe when people like you, deceived and drawn into this adventure, will be killed like dogs. I, a career officer who went through the war with the Germans, take the responsibility upon my conscience! I am sending you home!”

“What is this? It's over?” Turbin asked dully.

“It's ovew,” the colonel answered laconically, jumped up, rushed to the table, carefully scanned it with his eyes, clapped the drawers several times, pulling them out and pushing them in, quickly bent down, picked up the last stack of papers from the floor, and shoved them into the stove.

A black haze enveloped Nikolka's brain; he squatted down and, unexpectedly for himself, with a dry sob and no tears, began to pull the colonel by the shoulders, trying to lift him. Then he saw that blood was flowing from the colonel's left sleeve, and his eyes had rolled up to heaven.

Turbin was already squinting his eyes like a wolf as he ran. Two gray men, followed by a third, jumped out from behind the corner of Volodimirskaya Street, and all three flashed their weapons in rapid succession. Turbin, slowing his run, baring his teeth, shot at them three times without aiming.

The commander, who remained in the dugout by the phone, shot himself in the mouth.

The commander's last words were: “Staff scum. I perfectly understand the Bolsheviks.”

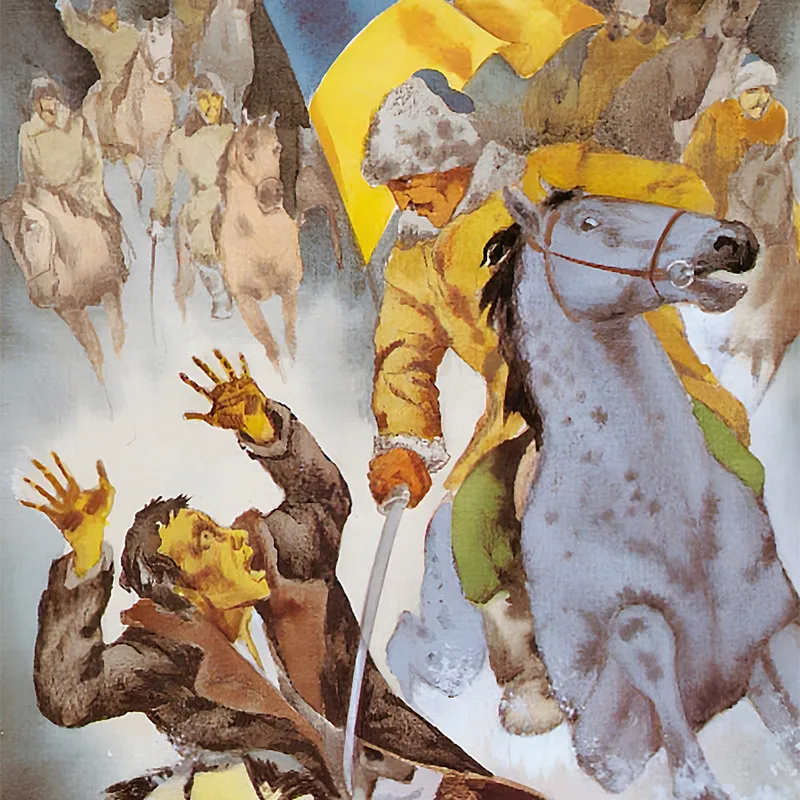

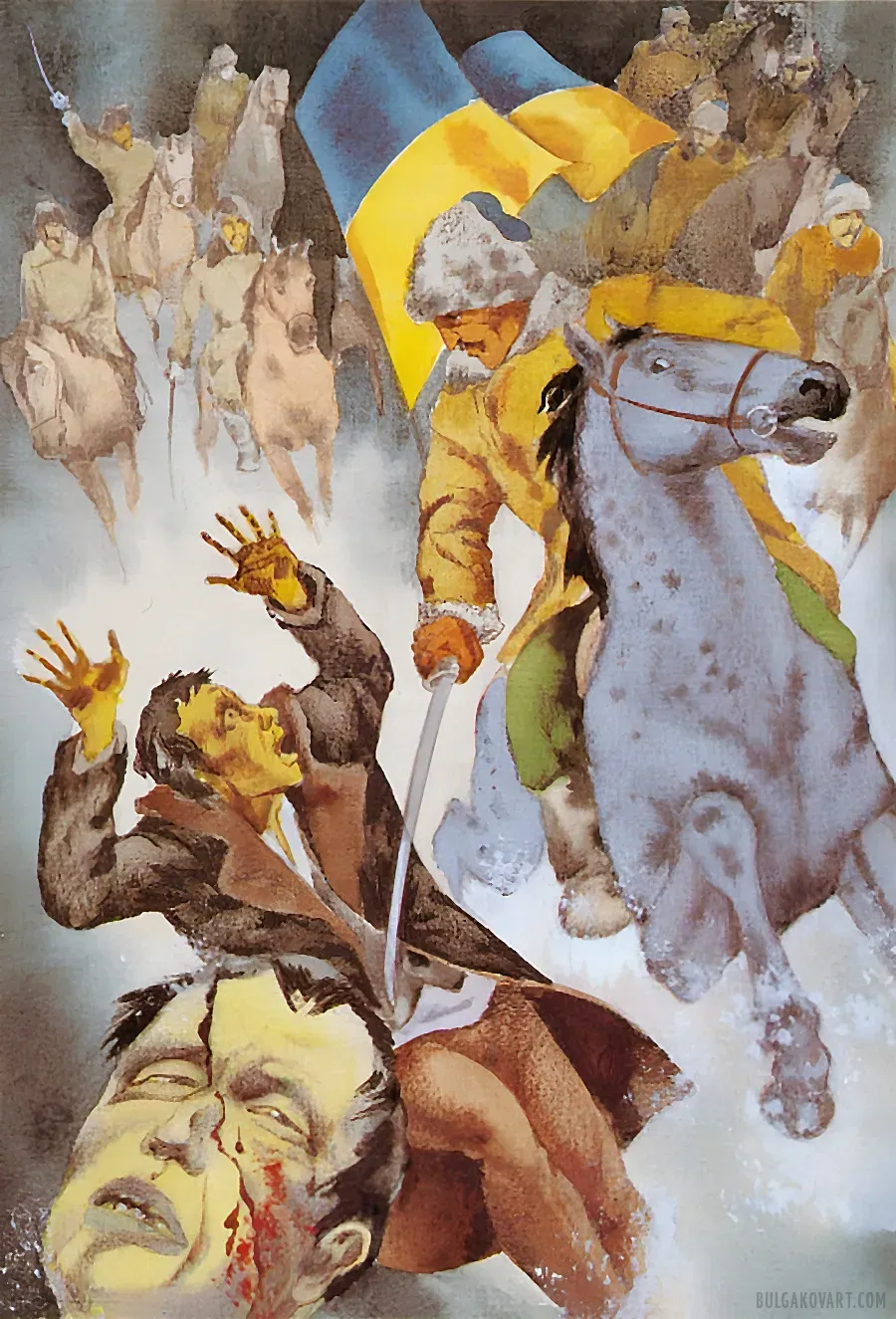

“Pan Sotnik, this isn't the document! Let me see...”

“No, it is," Halanba said with a devilish grin. "Don't fret, we are literate enough to read it.”

It's a good thing Feldman died an easy death. Sotnik Halanba didn't have the time. So he simply swiped his saber at Feldman's head.

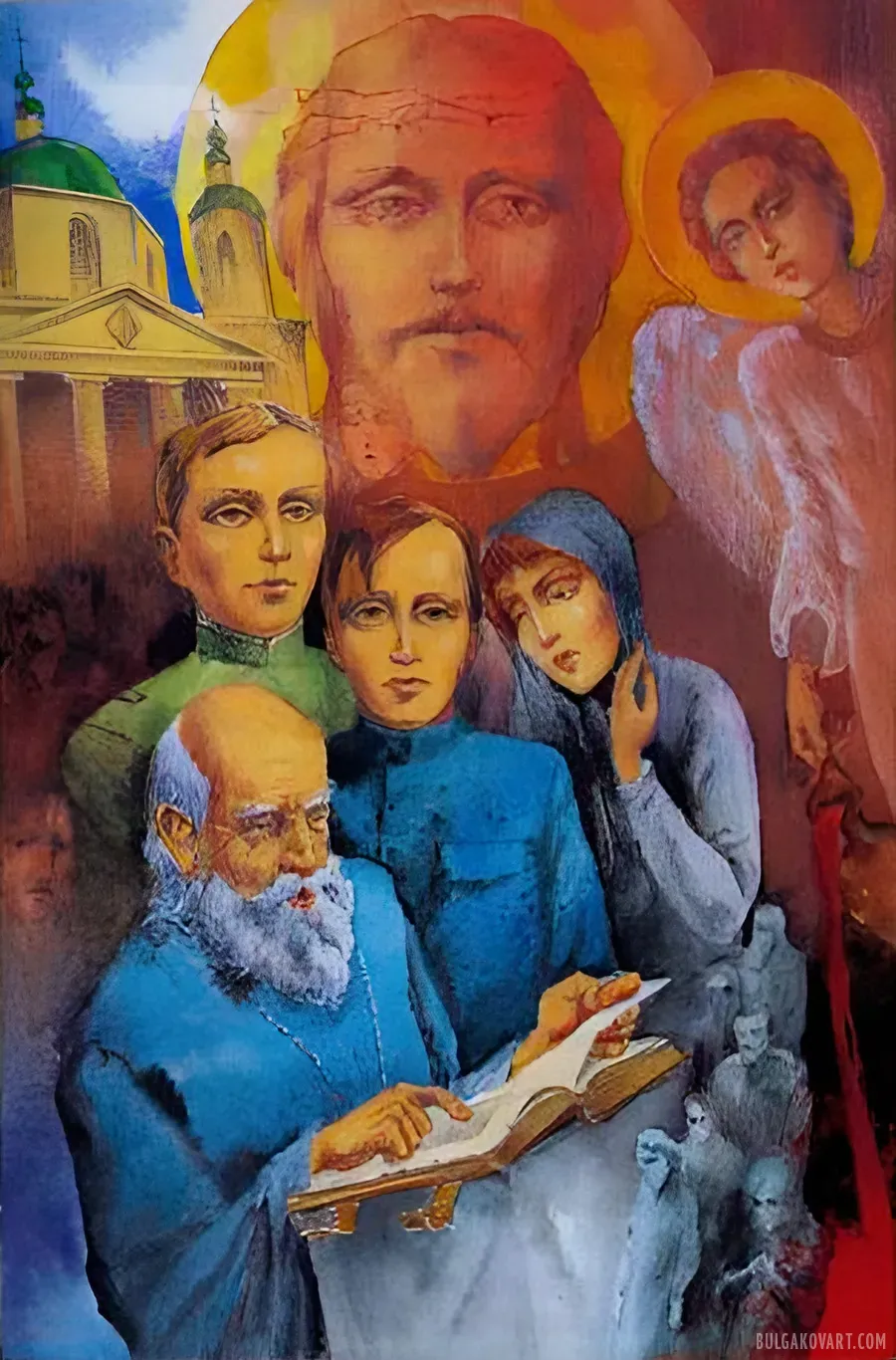

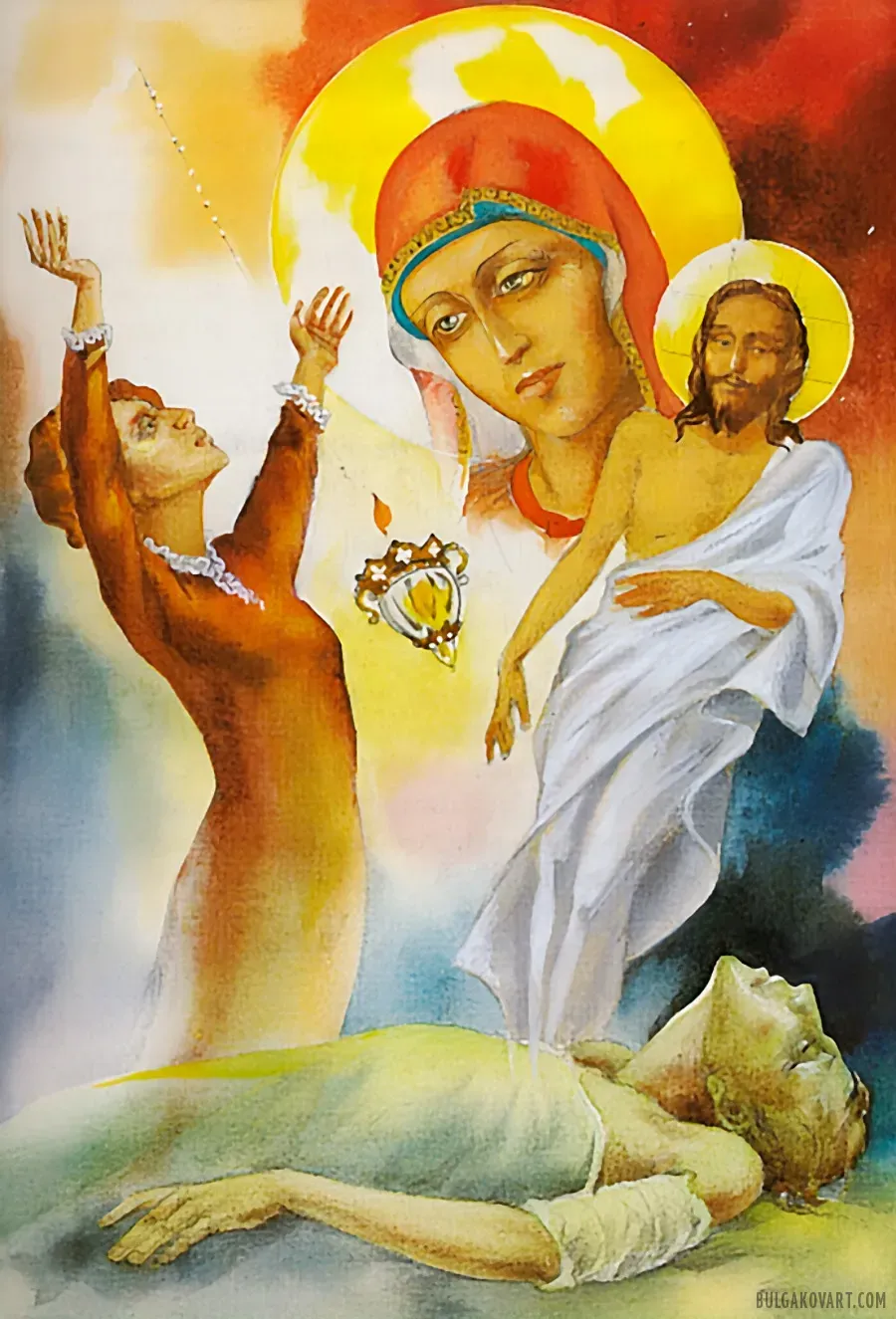

Elena, on her knees, looked up from under her brows at the jagged crown above the blackened face with clear eyes and, stretching out her hands, said in a whisper:

“You send too much grief at once, Mother-Intercessor. You destroy a family in a single year. Why?”

A heavy, absurd, and thick mortar was placed in the narrow bedroom at the beginning of the eleventh hour. What the hell! It will be completely impossible to live. It took up the entire space from wall to wall, so that the left wheel was pressed against the bed. It's impossible to live; you'll have to climb between the heavy spokes, then bend into an arch and squeeze through the second, right wheel, and with things too, and there are God knows how many things hanging from the left hand. They pull the arm toward the ground; the rope cuts into the armpit. It's impossible to move the mortar; the whole apartment has become a mortar apartment...

In the librarian's apartment, at night, in the Podil district, in front of the mirror, holding a lit candle in his hand, the owner of the goat fur stood naked to the waist. Fear jumped in his eyes like a devil, his hands were trembling, and the syphilitic spoke, and his lips twitched like a child's. His thin body, naked to the waist, was reflected in the dusty mirror, the candle burned down in his high-held hand, and a tender and delicate stellar rash was visible on his chest. Tears streamed uncontrollably down the patient's cheeks, and his body shook and swayed.

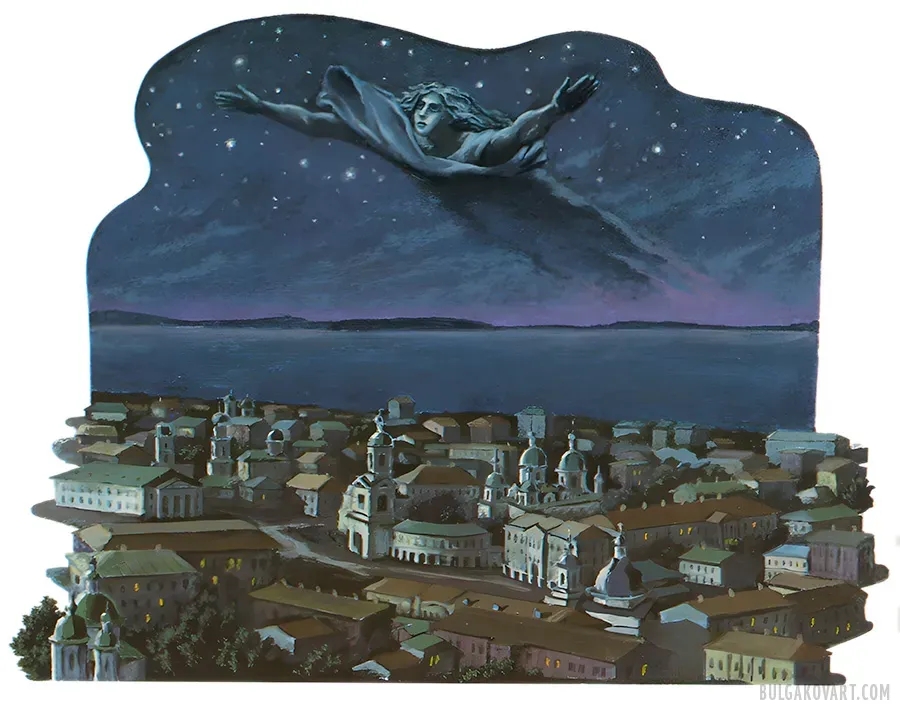

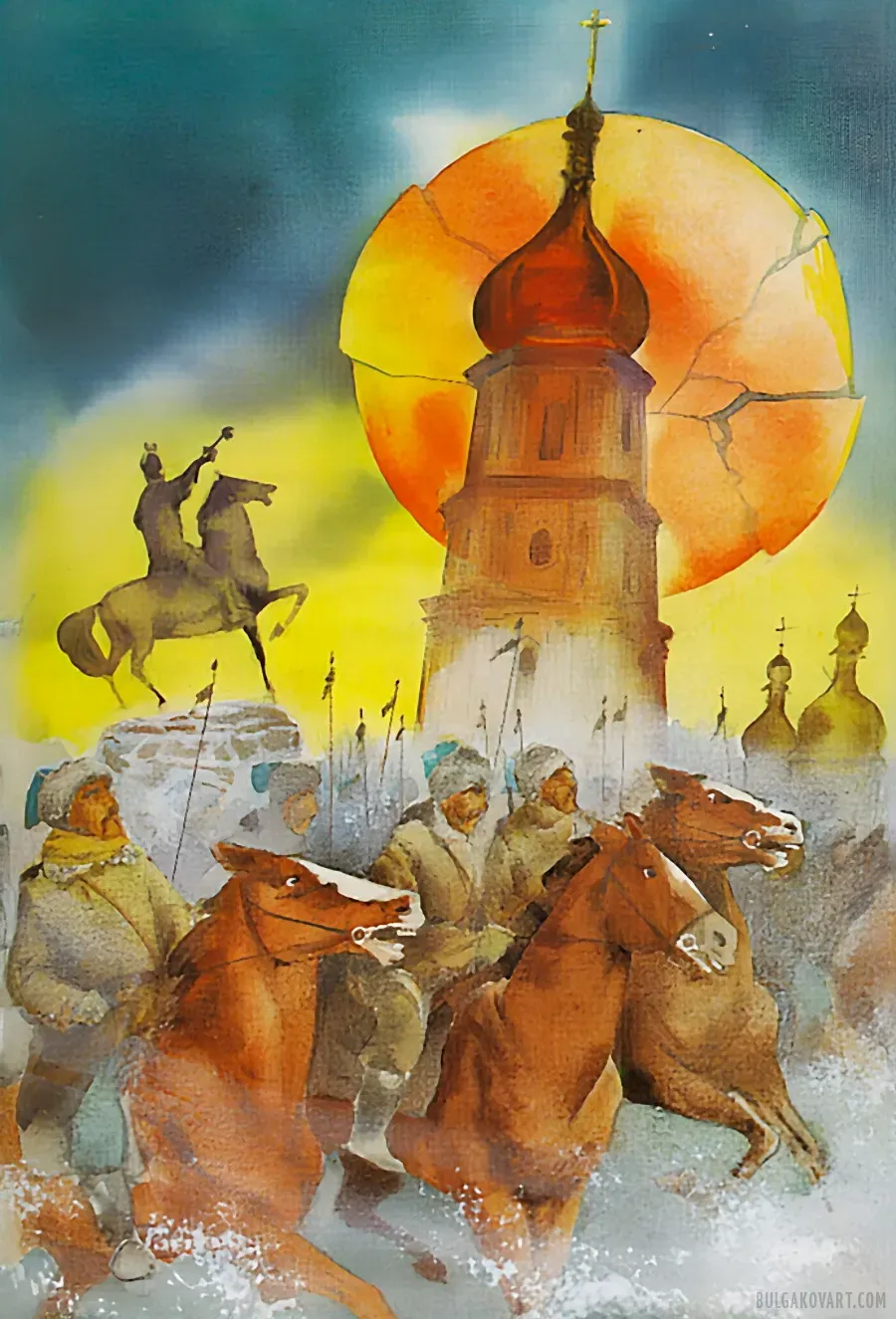

And the galloping Bohdan furiously tore the horse from the cliff, trying to fly away from those who hung heavily on his hooves. His face, turned directly into the red sphere, was furious, and he still pointed his mace into the distance.

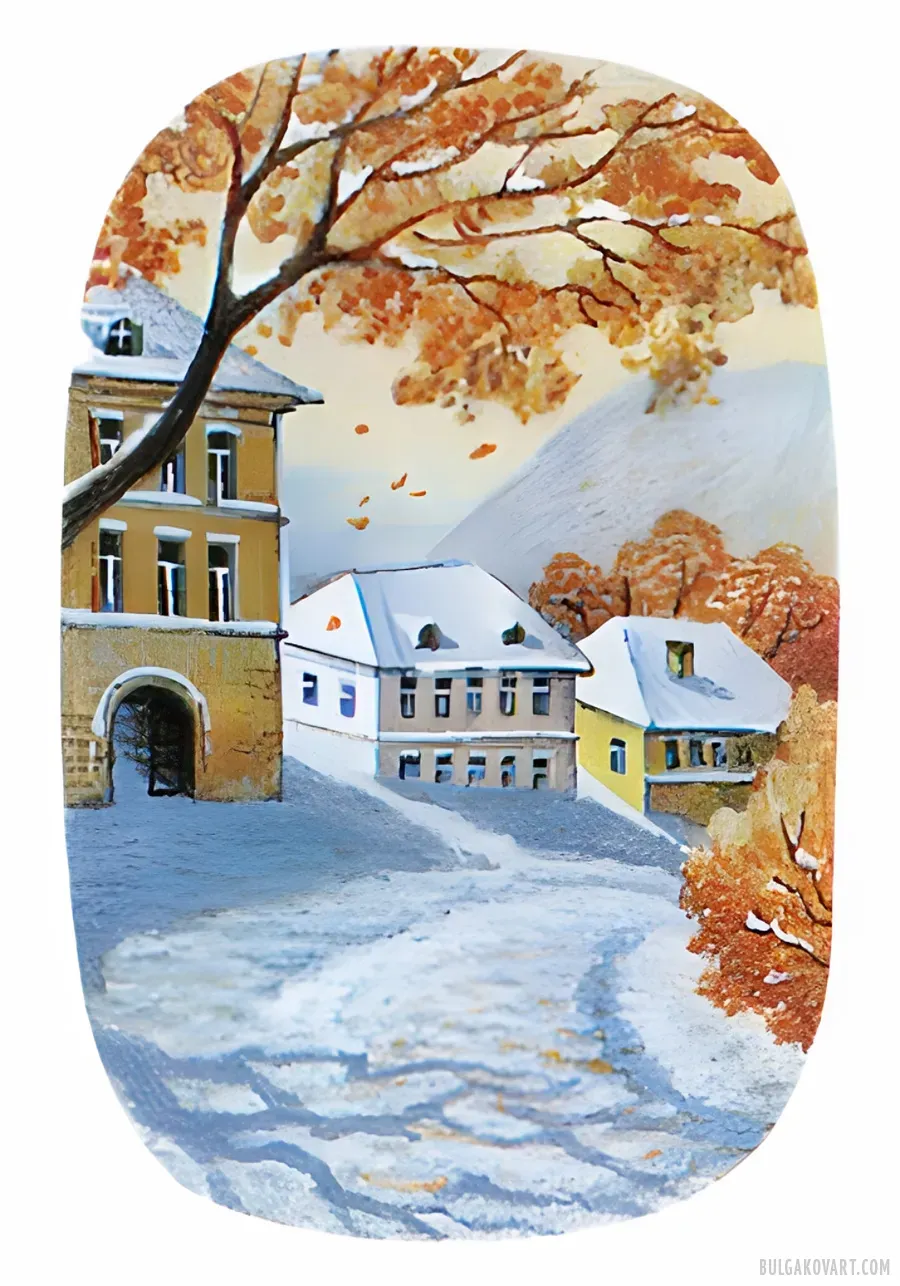

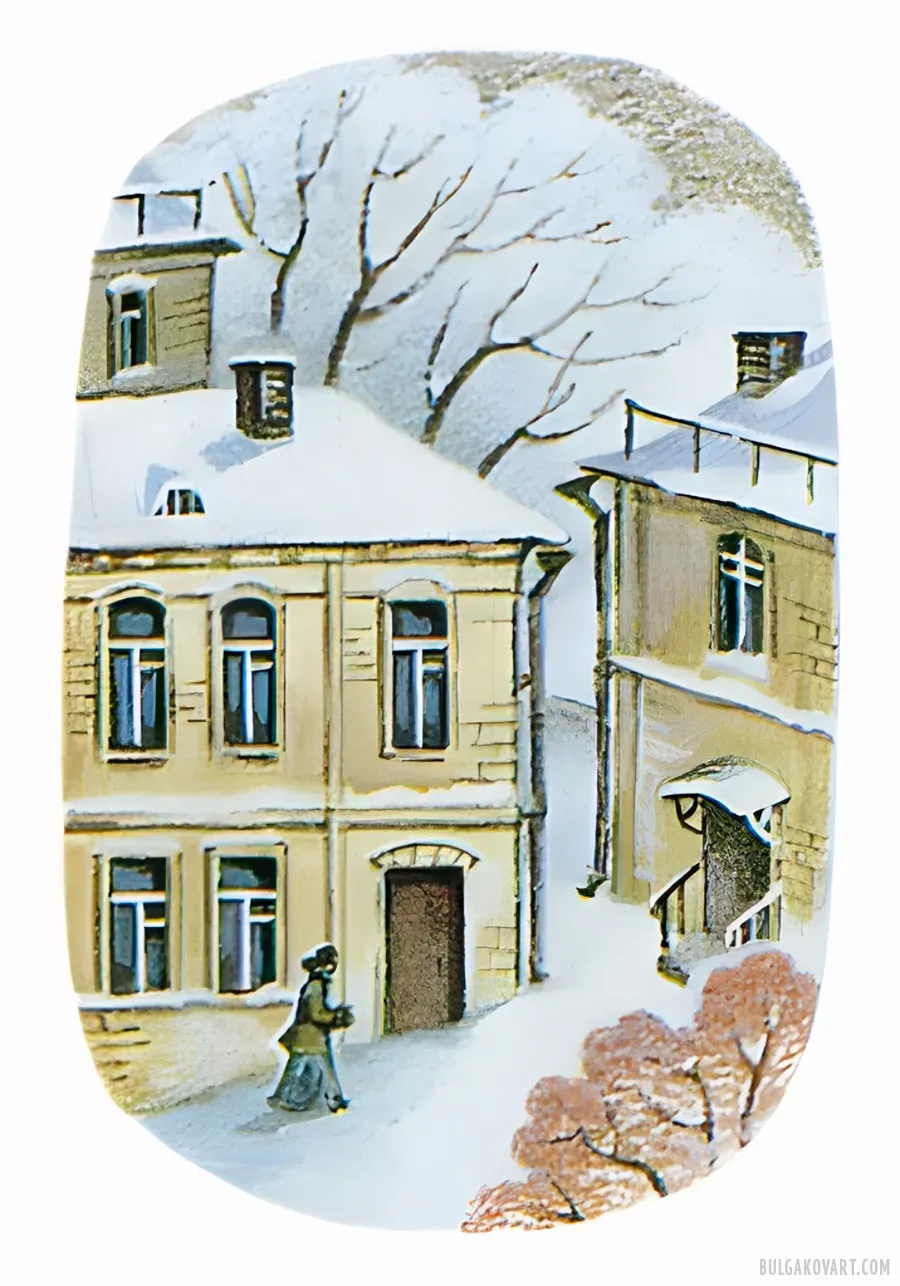

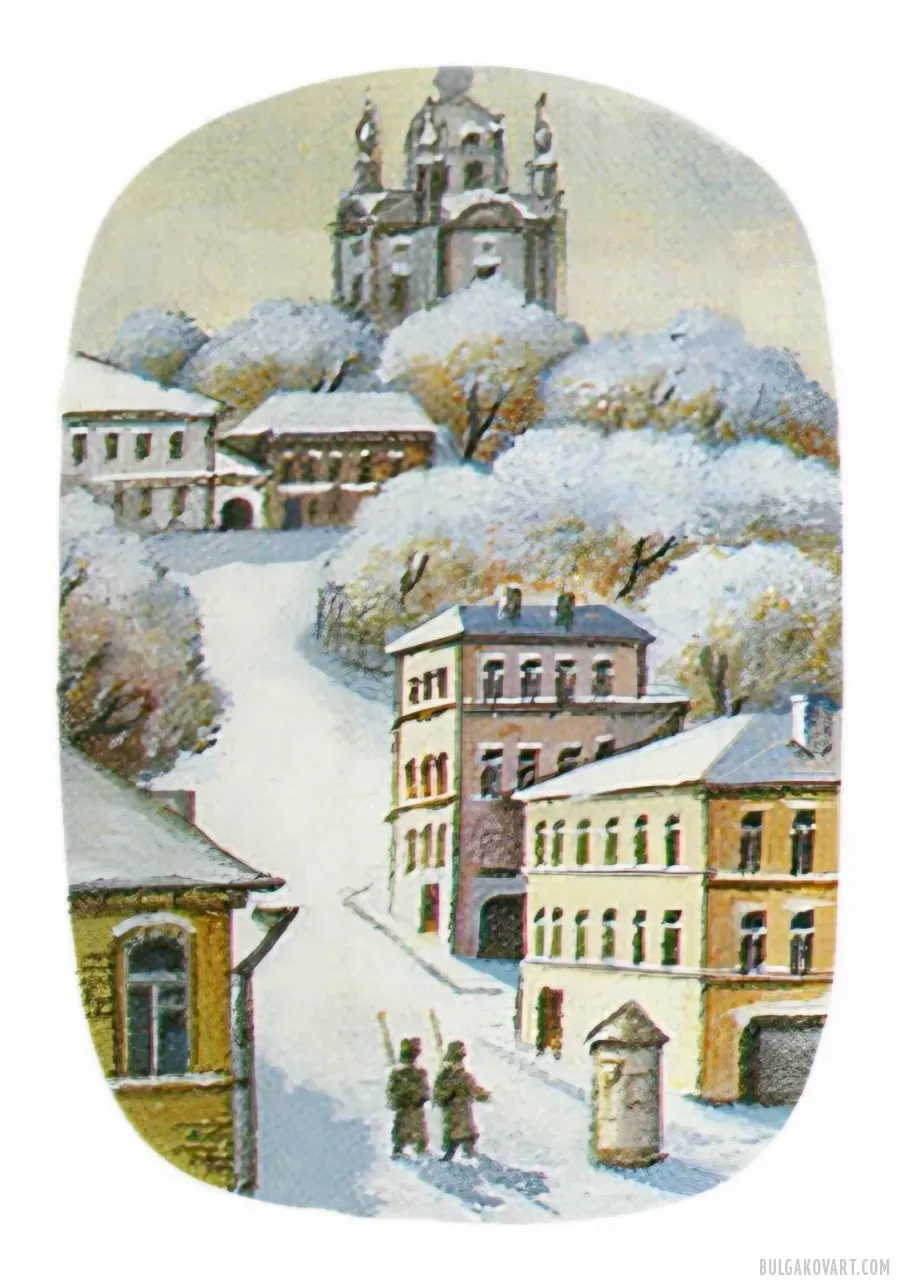

And as a bonus—several views of the City of Kyiv.